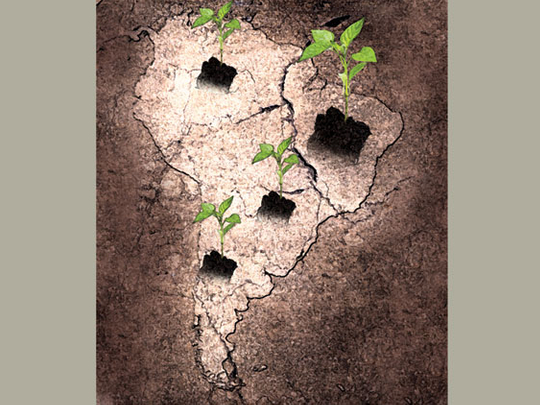

South America’s golden years are over. The commodity boom has peaked and the region no longer enjoys the abundant capital it did. Economies are slowing fast — look at Brazil’s, which is limping along.

Last month, the International Monetary Fund cut the region’s growth forecast for 2013 to 2.7 per cent — its worst performance since Lehman Brothers imploded in 2008. Meanwhile, democratic gains are threatened — look at the hyper-presidentialism of Venezuela or Argentina, whose leaders have had visions of never-ending rule.

That, at least, is the doom-mongers’ gloomy regional view. Farewell, salad days; hello, hair shirts and sunglass-wearing dictators. But is this the correct prognosis?

Forthcoming elections in Argentina, Chile and Venezuela, plus an early start to Brazil’s presidential campaign, suggest that democracy is more vigorous than ever. And there are good economic times still to be had. Commodity prices are higher than during the golden years of the mid-2000s. Capital remains abundant. Between 2003 and 2008, around $100 billion (Dh367.8 billion) flowed into the region annually; this year, inflows will top $300 billion.

Nonetheless, South America has reached a crossroads. Commodity prices and capital flows remain high; the snag is they are no longer rising. At the same time, the fortunes of many incumbents are good, but the excesses of the past are now showing. As a result, the region is experiencing a kind of political and economic bifurcation.

One group of countries, which includes Chile, invested the commodity windfall and is still growing strong. Another group, which has Argentina and Venezuela in its ranks, spent the boon on consumption instead. As Ernesto Talvi and Ignacio Munyo show in a fascinating Brookings Institution paper, they now suffer more growth-throttling bottlenecks.

Politics tells a similar story. For the past 10 years, the commodity boom boosted incumbents across the spectrum. High growth allowed them to spend more on needed social programmes. Millions also joined the ranks of the “new middle class”, who then returned incumbents to power.

Yet, while that economic growth helped whoever was in power, it did not always help democracy. In countries where constitutionalism was weak, it tended to get weaker, with some presidents unwilling to serve just one term or to compromise with opponents. In such countries, the forthcoming elections, like their economic slowdowns, are likely to be more traumatic.

In Argentina, over the past decade, Cristina Fernandez, with her husband and former president, Nestor Kirchner, concentrated power at the expense of the judiciary and the legislature. They planned to rule forever, but with the economy now sagging, polls suggest that at October’s midterm polls “Kirchner-ismo” will reveal itself as a spent force, with the opposition renewed by centrist dissidents from within the Peronist movement.

Then there is the extreme example of Venezuela, where Hugo Chavez systematically sought to weaken all political parties, not just the opposition. In 2007, he disbanded his Fifth Republic Movement and forced its merger with several smaller parties into Venezuela’s United Socialist Party (PSUV). As a result, the institutional processes of all parties weakened.

Recently, though, the Venezuelan opposition has coalesced under a single banner. By contrast, the PSUV is grappling with internal inconsistencies, especially since the death of Chavez this year, leading to policy paralysis. December’s municipal elections will reveal what voters think about Nicolas Maduro and the ensuing economic problems.

Chile’s presidential elections in November will probably see power transferred from one party to another for the second time since the transition to democracy 25 years ago, a sign of a strong constitutional democracy.

Lastly, there is Brazil, where the Workers Party has ruled successfully since 2002. But this long spell in power also weakened the effective capacity of the opposition. Indeed, Dilma Rousseff, the president, is likely to win next October’s election. Yet, the alliance between Marina Silva, a popular environmentalist, with Eduardo Campos, a can-do state governor, suggests the opposition is reforming, a healthy development for the balance of power.

What lessons can be drawn from all this? There is always the risk of over-categorisation but, broadly, there is seemingly one group of South American countries with strong constitutional process and stronger economies and another that is the opposite. It is the old liberal verity: Good politics makes good economics possible — and vice versa.

— Financial Times