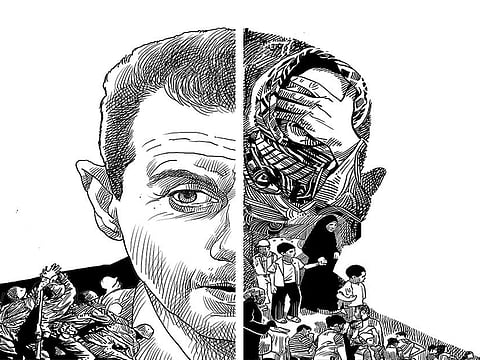

So, will Syria now be divided?

If Syrians fail to find a common platform to keep their country intact, foreign powers are ready to draw another Sykes-Picot

It was simply surreal reading the words of Israeli commentator, Zvi Bar’el, as he described Russia's federal plan for Syria as a model that aims to 'divide and rule' the Arab country. The oddity stems from the fact that ‘divide and rule’ has always been an Israeli tactic par excellence – one exacted with utmost brutality.

It was successfully applied in Lebanon, particularly after Israel’s invasion of that country in 1982, and also actively applied against the Palestinians. Moreover, Israel is itself the outcome of that very model, which has seen the historic division of the Arabs, and the breakdown of Palestine with the sole aim of satisfying the colonialist and racist ambitions of Zionists before their so-called War of Independence in 1948.

Alas, dividing the Arabs has been the modus operandi in managing conflict, regions and resources. Those who were not geographically divided, were fragmented based on various other ideologies – sectarian, tribal, regional and so on.

Recent comments by Russia's Deputy Foreign Minister, Sergei Ryabkov, that a federal model for Syria "will work to serve the task of preserving (it) as a united, secular, independent and sovereign nation," was not the first clue that division of that Arab country was, in fact, an option. Considering the current balances of power, in Syria specifically, and in the region as a whole, it might eventually, however unfortunately, become the only feasible solution for a country battered by war and fatigued by endless deaths.

Qatar and other Gulf countries have already rejected the federalism idea, although, considering the Syrian regime's latest territorial gains, and thanks to intense Russian bombardment, their rejection might not be a pivotal factor. The Turks also find federalism problematic for it will empower its arch enemies, the Kurds, who, according to the model will be granted their own autonomous region.

France and other European countries have varied positions on the issue, which largely vacillate between rejection and silence. But what matters most here is that the seemingly surprising Russian decision to withdraw most of its warplanes from the Syrian conflict was done with the prior understanding that the Geneva peace talks between the regime and its opposition shall proceed in a more serious fashion, and under the umbrella of an unprecedented unison between the United States and Russia.

This union is not at all far-fetched when one argues that the idea of this division has been implanted by the Americans. For one, the idea of slicing up Arab countries based on sectarian lines was the brainchild of the US military occupation that conquered Iraq in 2003. For all practical purposes, Iraq saw itself descending from a sovereign country (although ruled by an undemocratic government) into a state of bedlam, falling apart at the seams, where Kurds, Arabs, Sunnis and Shiites were embroiled in an inferno of civil war. Not only did the Americans do nothing to stop this, they actually set the foundation of and for that conflict, then orchestrated and manipulated it sufficiently and for its own benefit. Iraq's current division is the mutation of that monster created by the US over the course of a

In a recent testimony before a US Senate committee to discuss the Syria ceasefire, Secretary of State, John Kerry, revealed that his country is preparing a ‘Plan B” should the ceasefire fail. Kerry refrained from offering specifics, however, he offered clues. It may be “too late to keep Syria as a whole, if we wait much longer”, he indicated.

The possibility of dividing Syria was not a random warning, but one situated in a large and growing edifice of intellectual and media text in the US and other western countries. This was articulated by Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institute in a Reuter’s op-ed last October. He called for the US to find a ‘common purpose with Russia’, while bearing in mind the ‘Bosnia model’.

“In similar fashion, a future Syria could be a confederation of several sectors: one largely Alawite, another Kurdish, a third, primarily Druze, a fourth, largely made up of Sunni Muslims; and then a central zone of intermixed groups in the country’s main population belt from Damascus to Aleppo.”

What is dangerous about O’Hanlon’s solution for Syria is not the complete disregard for Syria’s national identity. Frankly, many western intellectuals never even subscribed to the notion that Arabs were nations in the western definition of nationhood, in the first place. (Read Aaron David Miller’s article: Tribes with Flags) No, the real danger lies in the fact that such a divisive dismantling of Arab nations is very much plausible, and historical precedents of such action abound.

It is no secret that the modern formations of Arab countries are largely the outcome of dividing the Arab region within the Ottoman Empire into mini-states. That was the result of political necessities and compromises that arose from the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916. At the time, the US was more consumed with its South American environs, and the rest of the world was largely a Great Game that was mastered and manned by Britain and France.

The British-French agreement, with the consent of Russia, was entirely motivated by power-lust, economic interests, political hegemony and little else. This explains why most of the borders of Arab countries were perfect straight lines. Indeed, they were chartered by a pencil and ruler; not organic evolution of geography based on multiple factors and protracted histories of conflict or concord.

It has been almost 100 years since colonial powers divided the Arabs, although they are yet to respect the very boundaries that they created.

Not only does the West loathe the term ‘Arab unity’, it also loathes whoever dare use what they deem to be hostile, radical terminology. Egypt’s second president, Jamal Abdul Nasser, argued that true liberation and freedom of Arab nations was intrinsically linked to Arab unity. Thus, it was no surprise that the struggle for Palestine occupied a central stage in the rhetoric of Arab nationalism throughout the 1950s and 60s. Abdul Nasser was raised to the status of a national hero in the eyes of most Arabs, and inversely, a pariah in the eyes of the West and Israel.

Modern examples of division of countries are ample. Libya was also broken up after Nato’s intervention turned a regional uprising into a bloody war. Since then, France, Britain, the US and others have backed some parties against others. Whatever sense of nationhood existed after the end of Italian colonisation has been decimated as Libyans reverted to their regions and tribes to survive the upheaval.

A rumoured ‘Plan B’ to divide Libya into three separate protectorates – Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan – was recently rejected by the Libyan Ambassador to Rome. However, Libyans presently seem to be the least relevant party in determining the future of their own country.

The Arab world has always been seen in western eyes as a place of conquest, to be exploited, controlled and tamed. That mindset continues to define the relationship between the two. While Arab unity is to be dreaded, further divisions often appear as ‘Plan B’, when the current status quo, call it ‘Plan A’, seems impossible to sustain.

The division of Syria may have started as a far-fetched idea, but is likely to gather momentum in the coming weeks. If Syrians fail to find a common platform to keep their country intact, foreign powers are ready to draw another Sykes-Picot, for all it takes is a ruler and a pencil.

Dr Ramzy Baroud has been writing about the Middle East for over 20 years. He is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an author of several books and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. His books include ‘Searching Jenin’, ‘The Second Palestinian Intifada’ and his latest ‘My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story’. His website is: www.ramzybaroud.net.