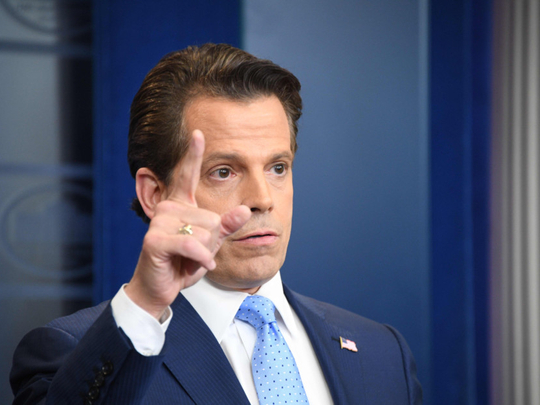

The short life of Anthony Scaramucci as White House communications director will be remembered with joy by some, or at least by me. His unbridled self-expression, in the grandest traditions of the First Amendment and the New York street corner, was more like a tornado of fresh air than a mere breath.

But the era of the Mooch was also guaranteed to be as brief as the life of a mayfly — for a serious reason. Important jobs like managing the president’s relationship with the press come with norms and customs: Unwritten rules that shape social relations in every culture, and that are based on cumulative wisdom and many decades (sometimes centuries) of trial and error. In his millisecond of public service, Scaramucci violated a stunning number of those norms — violations that could not be tolerated, even by United States President Donald Trump.

The lesson of the Scaramucci episode is therefore crucial for the Trump administration. Norms can be shifted, altered and changed; it’s always a mistake to assume they are invariant or inflexible.

It’s understandable that Trump’s closest advisers would consider themselves ideal for changing-making in the realm of unwritten customs. After all, they all took part in his history-making campaign.

And that campaign was characterised by breaking the unwritten rules. Trump repeatedly said more or less whatever was on his mind and didn’t just get away with it, but profited. Every time he broke a rule that the news media understood based on its own collective experience, it was newsworthy. The result, we now know, was a gigantic quantum of free press — all of it acquired quite legitimately, by being shocking.

Even when Trump got attention for breaking the rules unintentionally, as when the audio of his lewd conversation with Billy Bush surfaced, he survived and thrived, in direct contradiction to the conventional wisdom. The last candidate to break the rules unintentionally and get away with it was former US president Bill Clinton; but even he bowed to convention by expressing contrition and regret about his violations. And it’s unlikely that Clinton benefited from the publicity attendant on his lapses, as Trump seemed to do.

But running the country turns out to be markedly different from winning a campaign — and unwritten norms play a subtly different part. I’m talking about political rules of governance that have emerged from past practice.

The big difference is that the political rules almost all involve actors other than the president himself. In a campaign, the question ultimately comes down to whether voters will tick the box for the candidate. In governance, the question is whether different people holding different roles will cooperate on common projects.

Trump’s health-care debacle is a simple example. Instead of leading with a plan, as former president Barack Obama did, Trump deferred to Congress — and was unable (so far) to muster sufficient consensus within his own party to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Scaramucci’s norm-breaking was similar, if more spectacular and a good deal more entertaining. At the risk of stating the obvious, the White House communications director can’t act as though he’s the kingmaker for the entire administration. That means, of course, that he can’t denounce other senior White House staff in any way — much less scatologically, autoerotically and on the record.

The key point here isn’t so much the vulgarity, which was kind of beautiful in its outrageous way. Rather, it’s that the communications director can’t be the one to tell the world that the president’s chief-of-staff, who outranks him, is about to be fired. The moment Scaramucci foretold the firing of Reince Priebus, he was writing the chronicle of another political death foretold: His own.

No new chief-of-staff could conceivably tolerate a communications director who believed he could outflank a chief-of-staff. When it comes to hierarchical authority, in the end, there can be only one chief. So long as the communications director is a member of the White House staff, he has to fall under the chief. So it wouldn’t have taken a retired general like John Kelly. Any new chief-of-staff was going to cut Scaramucci loose. Those are the rules, whether you can find them in a book or not.

Part of Scaramucci’s charm was his apparent belief that the rules didn’t apply to him. When the violation is serious, we call this hubris, after the Greek tragedians. When the violation is more minor, we call it chutzpah.

The takeaway is that norms matter, because they constrain and direct us to act in ways that enable us to cooperate and get along. Left to their own devices, the Scaramuccis of the world — they are legion, and of all parties — would act out their own impulses, heedless of consequences. But getting things done requires limitations, self-restraints to facilitate working together.

Breaking the rules is more fun than almost anything. And there’s always a price to pay.

— Bloomberg

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg View columnist. He is a professor of Constitutional and International Law at Harvard University and was a clerk to US Supreme Court justice David Souter. His seven books include The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President and Cool War: The Future of Global Competition.