Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy’s announcement that he will seek the presidency again in 2017 should come as no surprise. Indeed, it was hard to take seriously his declaration, following his loss to the Socialist Party’s François Hollande in the 2012 race, that he was done with politics. Whatever you think about Sarkozy, there is no denying that he has never been one to stay out of the spotlight for long.

The truth is that Sarkozy never really accepted his defeat. Like Germany after the First World War, he instead became consumed with a desire for revenge, compounded by his long-held and poorly hidden lust for power.

Now, emboldened by Hollande’s unpopularity, Sarkozy seems to think that the French are ready to welcome him back. Instead of fretting about his own bad reputation, still reflected in public-opinion polls, he seems to be fantasising about a repeat of the 2007 election, when he triumphed easily over the Socialist candidate Ségolène Royal, Hollande’s former partner.

That may not be so unreasonable. Whether people like Sarkozy or not, the fact is that, during Hollande’s tenure, France’s social, economic and security situation has deteriorated — and many are holding Hollande directly accountable.

Current conditions may also hurt Sarkozy’s rivals within the Republican Party. In particular, Alain Juppé — Sarkozy’s main competition for his party’s nomination — could find that his moderate approach becomes a liability, especially now that Sarkozy is involved.

Both campaigns focus on the French identity. But whereas Juppé, who coined the term l’identité heureuse (the happy identity), aims to transcend the deepening divisions within French society, Sarkozy seems poised to capitalise on them, presenting Islam as a fundamental threat to the French way of life. Given the current popular mood — soured by recent terrorist attacks, from the murder of 86 people in a truck attack in Nice in July to the savage slaughter of a priest in Normandy later that month — Sarkozy’s approach may just work.

Consider the current debate in France over “burkinis” — body-covering swimwear favoured by some Muslim women. Surely in a free and diverse society, clothing that enables a group of women to enjoy a beloved activity comfortably should be welcomed. Yet, Muslim women are now being targeted for wearing burkinis, with police imposing fines and, as in a recent case in Nice, forcing women to remove layers on the beach. [On Friday, France’s highest administrative court suspended the ban on burkinis, that was imposed in a town on the Mediterranean coast. The ban in Villeneuve-Loubet “seriously and clearly illegally breached fundamental freedoms”, the court found. The ruling could set a precedent for up to 30 other French towns that had imposed bans on their beaches, chiefly on the Riviera.]

While some have denounced such bans, many citizens support them. I myself was on a French beach recently — one where the burkini has not been officially banned — and watched people’s appalled and scornful reactions to a covered Muslim woman splashing in the sea with her family. I even heard a young man announce that the image made him want “to shoot them all”. France’s diverse and open society has clearly fallen far.

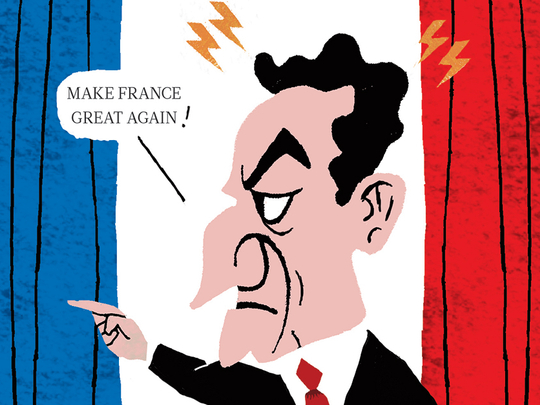

Sarkozy has read the popular mood well. He knows that the French are feeling defensive and angry, and he wants to use those feelings to win support — including by attracting votes from the far-right National Front’s Marine Le Pen. In this sense, Sarkozy resembles the Republican presidential candidate in the United States, Donald Trump, who has won the support of a swathe of angry voters by portraying himself as the saviour of a once-great country in decline.

But Sarkozy could well find that the very fears he is stoking make people afraid to choose him. With his buzzy energy and nervous tics, he may not seem like the kind of reliable and steadfast leader that a nervous country so desperately needs.

We shall soon know the answer. New public opinion polls will provide a strong indication of how the French perceive the newly-resurfaced Sarkozy. Do the reasons voters ended his presidency four years ago still hold? Or is the new context enough to make him seem like France’s best option?

More telling, of course, will be the party primary in November. Given Hollande’s rock-bottom approval ratings, it is widely believed that the winning Republican will be France’s next president. And though Juppé remains far ahead in the opinion polls so far, the French could reject his happy version of French identity, in favour of Sarkozy’s much darker one. I still believe that Juppé is most likely to emerge as France’s next president. In terms of age and profile, he resembles a French version of Hillary Clinton, the Democrat nominee in US — more practised in the exercise than the conquest of power. But fear is a powerful weapon and Sarkozy, like Trump, is eager to wield it.

— Project Syndicate, 2016

Dominique Moisi, a professor at L’Institut d’études politiques de Paris (Sciences Po), is senior adviser at the French Institute for International Affairs (IFRI) and a visiting professor at King’s College London.