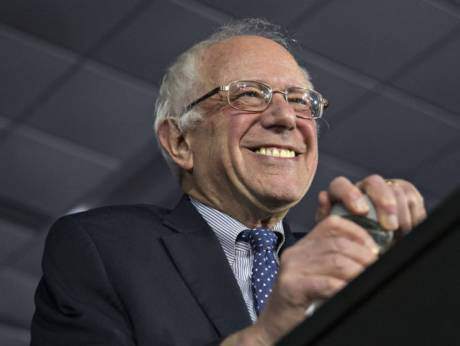

Billionaire businessman Donald Trump and socialist Senator Bernie Sanders won on Tuesday the Republican and Democratic contests respectively in New Hampshire, the first primaries of the 2016 election season. In a huge turnout in the Granite state, both candidates enjoyed healthy margins over their nearest competitors.

The size of the victories for Sanders and Trump in New Hampshire, which would have seemed implausible to many only a year ago, injects further uncertainty into this volatile election season. And it also increases the prospects of a third party run by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, another billionaire businessman albeit of a more centrist stripe than Trump.

On Monday, Bloomberg confirmed that he is seriously considering running as an independent and cited his disappointment at the rancorous rhetoric of candidates of both major parties, including Sanders and Trump, which he asserted is “distressingly banal and an outrage and insult”. Bloomberg, who believes that there could be significant ‘political space’ for a centrist, third-party candidate in this year’s race, probably needs to make a final decision this month as he would need to add his name onto ballots by early March in order to mount even a semi-credible campaign.

The continued appeal of the perceived insurgent, ‘outsider’ candidacies of Sanders and Trump underlines that much of the US electorate remains in a febrile mood following the uneven economic recovery of recent years, and the continuing domestic and international terrorism threat.

Since the beginning of 2016, a wide array of polls have shown that the overwhelming majority of the country (60 per cent or greater of the population) believe that the country is firmly on the “wrong track”.

This national pessimism is one factor contributing, right now, to what some have termed the ‘United States of Anger’. This is fuelling the intensity of the anti-establishment political mood which, if anything, may be growing almost a decade after the international financial crisis of 2008-09 began.

However, while the success of Trump and Sanders is remarkable, it is by no means unprecedented: US history underlines that income and status differences are potentially significant sources of political change. Both Trump and Sanders are appealing to many of those groups that have lost income and job security, including unskilled and semi-skilled persons working in manufacturing industries that previously operated with high levels of unionisation under the pressure of international competition. Hence, for instance, their anti-free trade rhetoric, including denunciation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership which the United States agreed, subject to US congressional ratification, with 11 other countries in Asia-Pacific and the Americas.

Such disaffected groups have significant potential claims upon federal and state government support. And these claims are potentially open to mobilisation by insurgent politicians, as both Trump and Sanders are now demonstrating, but as others have shown dating back to the 19th century, including the populist William Jennings Bryan in the 1890s.

The discontent of much of the 2016 electorate is not only driving distrust of government and politicians who are seen as part of the Washington establishment. It is one of the key factors contributing to sky-high rates of political polarisation in the country.

This could have crucial implications not just for the outcome of the presidential contest, but also public policy and governance too in Washington from 2017 given the significant prospect of gridlock where key issues, like comprehensive immigration reform, have been put into the deep-freeze because of differences between and within the parties. Indeed, in a political system that was built upon achieving consensus, polarisation is precluding the development of a range of short and long-term policy solutions in a host of areas from education to infrastructure, all of which undermines the long-term economic growth and vitality of the country.

While polarisation reflects the current levels of voter discontent, including growing divides over wealth and educational attainment that Trump and Sanders are proving skilful at tapping into, it is also driven by longer-term demographic and generational change. Thus, one of the most notable features of the contemporary political environment is the Republican Party’s heavy dependence on white, older, southern voters, whilst its Democratic counterpart has a more disparate coalition of African-Americans, younger whites, and new immigrants across the country, including the south, along the West coast, and also the North-east.

The last presidential race highlighted these stark partisan divides with Republican Mitt Romney winning a huge slice of the white electorate — almost 90 per cent of his support came from non-Hispanic whites. Yet, he still lost relatively narrowly to Obama, who had 95 per cent backing of African Americans, over 70 per cent of Hispanics, and around two third of Asian Americans.

The stark demographic, ideological and cultural cleavages in the electorate appear to be intensifying at the moment when the US electorate has become the most diverse ever in 2016. Nearly one in three eligible voters this year will be Hispanic, Asian or another racial minority. What this profound demographic shift underlines is that the US is on a trajectory to become, potentially around mid-century, a majority non-white nation and, at the same time, there is rapid ageing of the electorate.

Elements of the Republican Party, as seen in the divisive anti-immigrant rhetoric of Trump, are challenged by the changing social landscape of the country. However, some candidates such as Marco Rubio are promoting a more welcoming stance mirroring that of George W. Bush in 2004, who won 40 per cent of the Hispanic vote.

With Trump winning in New Hampshire, there remains a significant prospect that he will continue to disproportionately set the agenda for the Republican race for potentially weeks to come, including in South Carolina on February 20. Should this happen, it could further alienate key voting groups, including Hispanics. And as demographic shifts in population are working against Republicans, failure of the latter to reach out more aggressively to Democratic-leaning constituencies will undermine the prospects for the eventual Republican nominee winning in November against former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, who remains likely to beat Sanders, despite his New Hampshire win.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics