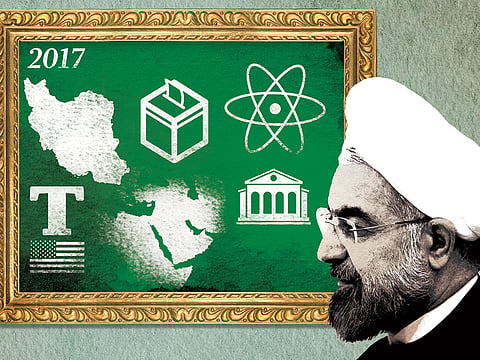

Rouhani faces real challenge in Iran’s 2017 election

Banks’ refusal to cooperate with ending sanctions and Trump’s election have wrecked Rouhani’s hopes of Iranian economic revival

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani is facing a very tough 2017, which will be dominated by Iran’s presidential elections due in May, when he was expected to be riding high on the flood of an economic upturn. Instead, he will face a resurgent conservative opposition. Rouhani staked his entire political future on the economic benefits that would come to the people from getting the nuclear deal through, but this has been destroyed by the refusal of the international banking regime to have anything to do with Iran, and by the imminent arrival of Donald Trump in the White House, who said that he would abandon the deal.

Rouhani heads the internationalist strand of Iran’s conservatives, as opposed to the more isolationist conservatives who flourished under the previous president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Neither are anywhere close to the more liberal Iranian politicians like Mohammad Khatami or Mir Hussain Mousavi. Rouhani believes that Iran can be both conservative and internationally engaged and he made a great political effort to find a way to get his country closer to the international community.

Rouhani’s strategy was based on an understanding that the ending of sanctions would bring a flood of companies anxious to do business in an oil-producing country that had been grossly underinvested for more than three decades. But things did not go his way. Firstly, the sanctions that were lifted were only those imposed over Iran’s controversial nuclear programme. What remained in place were other and much older sanctions, some of which go back to the first days of the revolution when the Iranians held the US embassy staff hostage for 444 days in 1979 to 1980. These and others linked to Iran’s sponsoring of terrorist groups have remained in place.

Secondly, the international banks are deeply suspicious of long-term American reaction to doing business in Iran. Some of the world’s biggest banks worked under the previous internationally-accepted trading regime and were outraged by attracting large fines from US banking authorities. They have told their clients that if they want to work in Iran, they will have to find other bankers.

Lastly, and maybe more importantly, are these factors: Iran remains committed to its active political interference in the Arab region. It supports large militias and political parties in Shiite-dominated Iraq. It is also one of the most active allies of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad; it is a leading supporter of the Al Houthi rebels in Yemen and it remains cooperative with the more sectarian opposition parties in Bahrain.

None of these point to any form of international acceptance for Iran, which will encourage Rouhani’s opponents. The leaders of the hard-line Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is delighted with the chance to get back the economic and political power it lost during Rouhani’s presidency, which will lead to a much more militaristic strand of politics in Tehran.

“Uncertainty over Trump’s Iran and regional policies, Iran’s presidential election in May and economic hardship that might lead to street protests will force the establishment to give more power to the IRGC,” political analyst Hamid Farahvashian recently told Reuters. Examples of how the IRGC has forced its views on Iran include the suppression of the students’ protests in 1999 and also the silenced pro-reform protests in favour of Mousavi that followed Ahmadinejad’s disputed re-election in 2009. The Guards are led by seasoned and senior commanders who idolise the Supreme Leader and are totally loyal to the ideals of the Islamic Republic, as well as enjoying considerable economic power through the Guard’s vast holdings.

It is not clear who the anti-Rouhani conservatives will find as their presidential candidate in the elections and typically these things are sorted out at the last minute as candidates wrestle with various rulings from the Guardian Council that vets and approves all candidates, leading to a vigorous season of electoral horse-trading as those who have been excluded fling their weight behind others who have been left to run. But it is clear that Rouhani will have a fight on his hands, and he cannot be sure of winning, given the poor impact of the domestically controversial deal with what Iran still calls the “Great Satan” in Washington.

There is another impending shift in Tehran as the political elite position themselves for the succession to the ill and ageing Ali Khamenei as Supreme Leader, which is a much more influential position than that of the president’s. Ayatollahs Sadek Larijani and Mahmoud Shahroudi are both strong candidates, according to Ali Hashem of Al Mayedeen Online. Both have a record of serving in official positions that go back a long way and are already members of the Assembly of Experts. Larijani is the head of the judicial authority and Shahroudi is the head of the arbitration council that mediates disputes between the three branches of the state. But an intriguing third possibility is Rouhani, who holds the special distinction of having been with Khomeini in Paris before the revolution, and so mixes modern experience with the extra authority of being part of the original revolution.