Arabs have been doomed since the mid-20th century to the rule of regimes centred around “inspired” or “eternal” leaders who believed they alone were capable of thinking and deciding what was good for their people and countries. The motto imposed upon the Arab masses in this case resembles the words of a classic Arab lyric where the poet says: “Laila follows the faith of Qays, wherever he turns she turns and whatever he likes she finds beautiful”. It is Laila, in this case, that the Arab people resemble, blindly but forcibly following the “inspired/eternal” leaders who, over time, became self-convinced of being the beloved of the people. Such presumed love for the “inspired/eternal leader” is usually insured by multiple internal security systems imposing it on his subjects and posing a dire threat upon whoever disagrees with his rule, for love can never be imposed or generated by fear or force.

In recent Arab history, we witnessed decisions and adventures of some Arab leaders labelled as “mad” by intelligent observers, yet viewed by some as “miracles” and were sold to the people to evoke applause. Such acts of utter deception hit the people with the same sickness that afflicted the dying Ottoman Empire in its last days, where poverty-stricken people, unable to feed themselves, were thanking the Most High for providing them with a great leadership, while internal security systems were completely consumed in providing security not to the people but to the leader in order to remain an unchallenged and unaccountable power.

Let us consider the case of “the Leader” before the inception of the Arab Spring, who attributed all the honours, victories and “inspired” accomplishments to himself alone, and ask: How can we define such a leader? Or, rather, what kind of a “state” was ruled by this leader?

Take for example Tunisia. A compounded answer to both questions is that the state was built to be run without the free expression of the people or principles of accountability along with rampant corruption and a country milked dry by the family of the leader and his cronies, widespread unemployment and rising inflation that eradicated the middle class and created a minority of the super rich while the vast majority of the people lived in utter poverty. Such a situation was usually aggravated by acts of repression employed by the state to subdue its people, coupled with the blind loyalty of the especially tailored military forces and police to protect the “inspired/eternal leader” instead of devotion to safeguard national interests.

We can imagine the extent of damage caused by such regimes which lasted for years and years and we can still hear the agonising moaning of the people because of extreme pain inflicted on them under the guise of “confronting colonialism and imperialism” with tools enslaving the people in a much worse manner than the old rule of colonial powers. All civil society bodies were eradicated or subdued to the will of the leader. All opposition figures were considered traitors and the wealth of the nation was blundered to the sole benefit of the family of the leader and all his cronies. Systematic distortion of principles and values took place in such countries, which are now in need of a long process of restoration, leading creative minds to flee their lands and seek a better future in a free world, yet haunted by the agonies of their homelands.

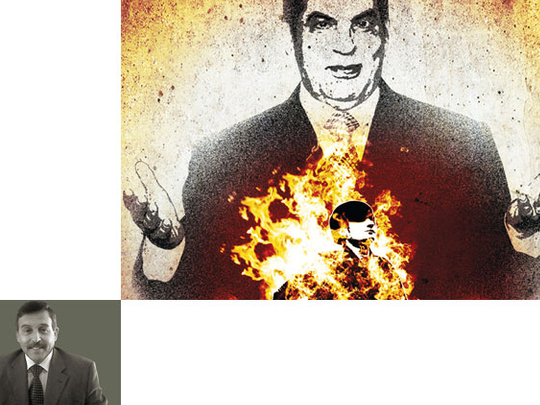

It was not strange that under such conditions, the Tunisian young man, Al Bouazizi, set himself on fire, unaware that he was igniting a raging fire in a number of Arab countries, whose flaming sparks have now spread along the entire Arab world. When dictatorial regimes become old, they freeze into dumb, deaf and blind systems oblivious to the extreme afflictions they brought on their people.

Arab youth, under such regimes, found themselves as subjects with no future in sight. Thus, a near-suicidal hopelessness grew in their hearts and minds that led them to revolt regardless of any cost. The current Arab uprisings that were born on Arab streets without a ready set of leadership that in the past led to famous revolutions, revealed determination with efficiency towards digging the graves for the dictatorial regimes that long abused and enslaved their peoples. The new forces have become inspirational symbols as well as master teachers to the elite of the former opposition groups who were not effective enough in their attempts to topple these regimes. Indeed, these new breeds of revolutionary elements have surfaced as leaders who advocate change and modernisation to uplift their countries from their stagnant, corrupted past. Because the liberal and progressive intellectual elites played no role to ignite the fire of change in the Arab Spring and are plagued by internal conflicts among themselves, other forces with religious tendencies have been rising in what appeared as a balance being created against the immoral corruption of the old dictatorial regimes.

The French thinker, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, had once said: “Every human being has the full right to put his life on the line in-order to save it”. The era of the bankrupt, old elites has gone for good. So has the era where a leader tamed such traditional elites to mainly serve him. Yet, the emergence of these new elites does not mean that the ancient powers have given up on their hopes to reverse the course of change of the Arab Spring and return to the old order, but “the barrier of fear” has been eradicated for good in the hearts and minds of the Arab people which, one hopes, shall render such schemes null and void.

Professor As’ad Abdul Rahman is the Chairman of the Palestinian Encyclopaedia.