Despite religious injunctions, international laws and exhaustive military manuals regulating belligerents' conduct in war, protracted wars seem to degenerate inevitably. There is a progressive erosion of ethics; even the best armies encounter indiscipline, unauthorised vengeance, crimes against women and children and disregard of human rights.

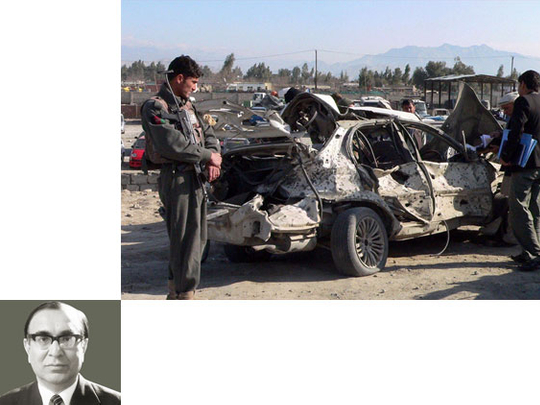

The 11-year-old war in Afghanistan is beginning to be a case history of this deterioration. Perhaps nothing like what happened to the hundreds of inhabitants of My Lai in Vietnam on March 16, 1968 has taken place in Afghanistan but civilian casualties are on the rise, as, indeed, are the instances of wanton disregard for human dignity. It is not just the indiscriminate cruelty in the night raids of the Special Forces or the ‘mistaken' bombing of Afghan wedding parties; rogue elements — individuals or small groups — from the Nato-Isaf (International Security Assistance Force) troops behave disgracefully.

This may indicate stress in a hostile environment, sheer fatigue, frustration at the lack of success and racist and religious bias in the lower rungs of command but, apart from tarnishing the image of the United States and its allies, it complicates the implementation of the existing plans to disengage from the conflict.

The situation since the beginning of 2012 has been egregious. Pictures of marines urinating on the bodies of slain Taliban fighters have gone round the world; so has the news of the bloody sequel to the ‘accidental' burning of the copies of the Quran and of an American soldier, reportedly either deranged or drunk, shooting 16 Afghans, including nine children dead. Retaliation has come not just from the Taliban but also from members of President Karzai's security forces.

Internal settlement

As the Afghan conflict degenerates, the danger of eventual disengagement leaving behind an unmanageable anarchy increases. That the movement towards disengagement is irreversible can be seen from President Barack Obama's latest pronouncements about winding down the war ‘responsibly' and from what we know of his recent consultations with UK Prime Minister David Cameron. Regardless of the compulsions of the American presidential election, the forthcoming Nato summit in Chicago must rise to the challenge of making qualitatively different policy adjustments to achieve this objective.

The guiding principle will have to be a higher priority for an internal Afghan settlement than for the strategic gains of outside powers. The basic elements of a settlement may include the following: farewell to arms; inclusion of the Taliban in a national government; consensus on constitutional reforms including greater devolution of power to provinces within the framework of a viable united state; size and composition of the Afghan National Army and security forces; and the disbanding of militias maintained by the warlords or their absorption into the agencies and forces of the state.

Short-sighted social, ethnic and sectarian engineering by any outside power will only perpetuate tensions as it, indeed, has done since 2001. Diversity in Afghanistan is no different from diversity in other regional states.

The US-led interventionist powers must honour the sovereignty of Afghanistan and respect the prerogative of its government to negotiate the grant of such facilities to them. The Chicago summit ought to substantially scale down plans for a huge Afghan National Army to align them closer with national needs and means. Raising an army that can only be fractionally financed by Kabul and that is primarily designed to fulfil Nato's own ambitions in a contested region will only make Afghanistan controversial and prone to instability. A policy of positive neutrality will give the resurrected Afghan state time to establish itself strongly.

Regional countries must be drawn into a UN-sponsored arrangement of non-interference in the affairs of Afghanistan. Without prejudice to such treaties as Kabul may enter into with neighbouring states, the UN Security Council should be the guarantor of non-interference. Regional associations such as South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, Economic Cooperation Organisation, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation should be encouraged to network to assist Afghanistan re-build its economy and realise its potential as a natural hub of regional and international trade. A greater role for the GCC states in the economic field should be seen as a natural extension of the Qatar process for peace.

In the short run, the powers that militarily intervened to overthrow the Taliban regime will be seen to have been forced to substantially curtail their war aims. But in a long-term projection, this would be the best way of salvaging the nobler elements in their decade-long military campaign in this Asian land. Above all, they would have extricated themselves from a dilemma that could only get worse with time.

Tanvir Ahmad Khan is a former ambassador and foreign secretary of Pakistan.