Petrified unity in terror-struck Berlin

For now, Germany remains in balance, but the number of measures that can be imposed without changing the constitutional character of the country is narrowing

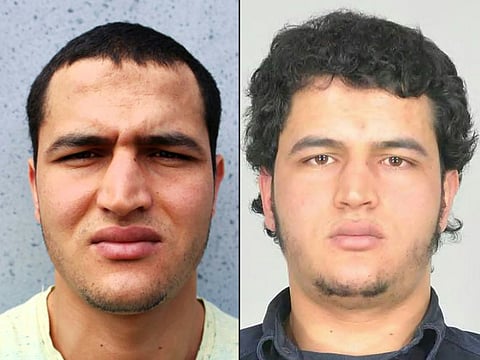

It has been almost a week since a truck ploughed through a Christmas market in the heart of Berlin, killing 12 people and injuring dozens. In the following days, the city, the country — and all of Europe — were gripped by the continent-wide manhunt for the suspect, Anis Amri, who was shot and killed by the Italian police last Friday.

As I try to get ready for the holidays — to keep things normal — I find myself anxiously looking for signs of how my fellow Berliners are handling it all. When I wait at the train station, I wonder if the people next to me are scanning the platform. Are they afraid? And with a momentous national election next year, will that fear translate into political panic?

I find no change — which is both a good and a bad thing.

Certainly, sadness prevails in Berlin. At Breitscheidplatz, many have left flowers and candles. Some cry. “I just don’t get it,” said a man who lives nearby. “We have helped so many. Why do they attack us?”

But there is also calm unity. “No matter where you’re coming from, we are one, and we are strong,” somebody wrote on a cardboard sign at the site of the attack. At least in Berlin, there are few demands for walls, or bans on Muslim immigrants.

It wasn’t a given that calm would prevail. In Germany, 2016 started off with rage. On New Year’s Eve, gangs of young men harassed, abused and robbed hundreds of women at the main station in Cologne. Most of those the police arrested were North African migrants. Anti-immigrant sentiment surged; trust in the government, and in Chancellor Angela Merkel, plummeted. Attacks on shelters for asylum-seekers rose. This rage is still there, of course. “Welcome, murderers, to Merkel’s multicultural slaughterhouse,” somebody wrote last week on the Facebook page of Beatrix von Storch, a prominent figure in the far-right Alternative for Germany party. Marcus Pretzell, the head of the party in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, wrote, just an hour after the attack, “These are Merkel’s dead.”

But the rage seems contained. Last Wednesday, the anti-immigrant Ein Prozent (One Per cent) initiative demonstrated in front of the Chancellery. Several high-ranking members of the Alternative for Germany participated, but only a few dozen protesters showed up.

Police officers gated off a section in front of the building, enclosing the small and freezing crowd in the dark. The protesters were only a few kilometres from the mourners at Breitscheidplatz, but in a different world. Here we are, I thought, the angry and the sad, confined in their respective corners of the public sphere.

German public sentiment is polarised, but stabilised. Contrary to what was feared, the terrorist attacks this summer in Ansbach and Wuerzburg have not significantly increased Alternative for Germany’s standing in national polls. My guess is that the Berlin attack will not change much, either.

One reason for Germany’s fairly calm response is that Germans were prepared. New York, London, Madrid, Paris, Brussels — people in Germany knew something similar would happen to them someday. They had time to watch, and learn. How to mourn, how to not overreact.

Over the years, the western world has developed a set of rituals in response: The lighting of candles, the pilgrimage to the sites of the attack, the defensive occupation of public spaces, the public oath by our representatives to not succumb to fear, the public profession to our liberal values. Last Tuesday, the Brandenburg Gate was bathed in lights of the colours of the German flag. The posting of hashtags of solicitousness is the prayer of our secular times. Even the far-right expressions of wrath, the call for an eye-for-an-eye, are part of the ritual. The populists’ exploitation of the anguish over terrorism has become part of the western post-attack script.

Of course, while rituals are comforting, they risk losing their meaning through repetition. We do not succumb to fear, but as we repeat it, we risk ending up holding the empty shells of former truths.

The same is true for the political post-attack ritual of promising harsher security measures. “It’s always the same after something happened,” said a man at the Chancellery protest. “They keep promising change and doing nothing.”

He’s not exactly right: In recent years, Germany has introduced significant changes to its asylum laws, as well as to its security apparatus. But his sentiment is widely held on both the Left and Right. And the number of measures that could be imposed without changing the constitutional character of Germany is narrowing. Which means: The frustration of those demanding a strong state response is bound to persist.

For now, Germany remains in balance, but it ends a crazy year huddled in the cold comfort of petrified division, united in helplessness.

— New York Times News Service

Anna Sauerbrey, a contributing opinion writer for the International New York Times, covers German politics and culture.