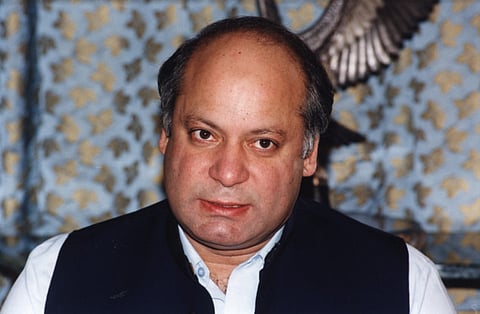

Pakistan’s elite should come clean on graft

Following the revelation through the Panama Papers of Nawaz Sharif’s children as offshore company holders, a thorough investigation is needed

In the wake of the global fallout from the Panama Papers scandal, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif reacted predictably and swiftly. He went on national television to defend his two sons, Hussain and Hasan who were linked to assets worth millions of dollars in offshore safe havens, which was revealed in the leaks, to buy top-of-the-line property in the UK.

The revelations have also exposed overseas assets worth millions of dollars belonging to Maryum, Sharif’s daughter, according to some his political heir apparent.

Sharif spoke at length about his family’s political history, their exile to Saudi Arabia following a 1999 military coup, and the subsequent resurgence of their family’s business through the establishment of a steel factory in Saudi Arabia. Faced with demands from opposition leaders for Sharif to come clean, the prime minister announced the establishment of an independent commission led by a retired judge to probe the allegations.

Though Pakistan’s opposition parties, one led by cricket legend turned politician Imran Khan, have demanded a thorough investigation by a more independent mechanism than the one offered by Sharif — there is indeed a risk of the issue being eventually shoved under the carpet.

The history of corruption allegations and their eventual fate in Pakistan leaves much to be desired. In Pakistan’s 69-year history, there has hardly been a sustained and long-term attack on corruption surrounding the rich and powerful.

Consequently, on the streets of Pakistan, a widespread acceptance of corrupt practices surrounding government functionaries, the police and elements of businesses must come as a powerful reminder of a problem too large to be curbed in one go. In brief, ending corruption in Pakistan appears to be an evidently uphill battle. But in the wake of the Panama leaks, the moment to tackle this problem aggressively may have now arrived. Meeting this challenge as a pre-requisite to saving Pakistan’s body-fabric from corruption becoming almost a cancerous ailment, must now be a top national priority.

For long, powerful individuals, notably politicians, businessmen and the landed gentry have taken pride in keeping overseas assets, without ever having to account for their wealth to anyone.

Ironically, Pakistan in the process has become one of the world’s poorest performers on matters related to collecting taxes. Although successive governments have talked about sweeping improvements to Pakistan’s tax collection system, none has succeeded so far in bringing about a badly needed radical uplift.

Now, the case of Sharif’s children is not immediately just about the issue of keeping illegal wealth in an overseas safe haven. The accounts in offshore havens themselves are supposedly legitimate. Yet, the key issue relates to forcing the prime minister’s children to not only provide full details of their assets. It is also absolutely vital for an independent investigator to verify exactly where the wealth came from, and share those details publicly.

In sharp contrast to the dismal track record of successive Pakistani regimes in battling corruption and coming clean, the resignation of the prime minister of Iceland in the wake of the Panama Papers, provides a timely insight to the way that national leaders ought to behave. Within days of the revelations and faced with a public protest, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson simply quit his job rather than fight back recklessly.

For Sharif, a failure to come clean on this issue will only reinforce the public’s view that the top elite in Pakistan routinely remain above the law. Consequently, the implications for Pakistan’s future can only be more severe than seen thus far.

If indeed this latest storm in Pakistan ends with the proverbial dust just settling without any casualties representing individuals in high places, the country’s ruling structure will simply not be able to lead any future initiatives to curb corrupt practices. After all, members of an already deeply sceptical public will have reason to ask, if indeed they ought to embrace progressive reforms against corruption while the top elite continue as usual.

Already, a range of Pakistan’s institutions dealing with daily life, from the police to different parts of government administration, function without tough reforms in place to end graft. Tragically, such institutions have only become immune to reform in recent years, as politicians have felt duty bound to curb their independence.

Cases such as that of Mohammad Ali Nekokara, a well-respected senior police officer posted to Islamabad, clearly proves the point. He was dismissed by Sharif’s government for refusing to use excessive force against opposition protestors including women and children gathered outside the parliament in Islamabad. On the contrary, a bloodbath involving harsh methods against unarmed civilians may have secured Nekokara his job, though not the widespread respect he earned across Pakistan for remaining conscientious while on duty.

Going forward, whether it’s the matter of remaining true to the best democratic traditions or abiding by the top most and globally accepted norms against corruption, Pakistan’s present day ruling structure is indeed failing. It is too early to know for certain if the controversy surrounding Sharif will eventually take its toll upon his government or blow over just like many previous storms in Pakistan’s history.

A failure to take Pakistan’s ruling elite to task will only lead to the country becoming financially, morally and ethically more impoverished with the passage of time.

Saving Pakistan can only be done if the embarrassment surrounding Sharif today leads to a long overdue and massive attack on corruption in the highest of places.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox