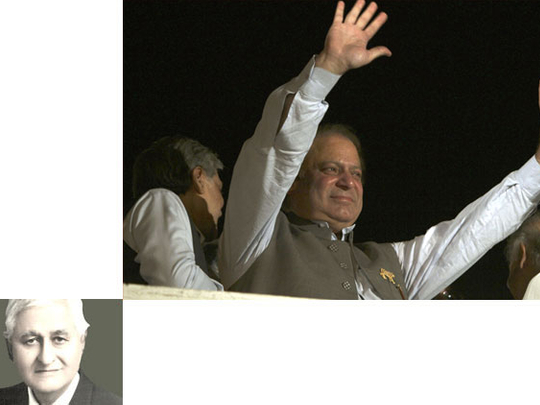

While all the official results were yet to come in yesterday, the trends were clear. Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) party, though short of getting an absolute majority in the National Assembly, was poised to head the new government in Pakistan.

Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehrik-i-Insaf (PTI) party looked set become the second-largest party in the National Assembly, edging out the ruling Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). The PTI has done well, even if not to the extent expected by its now anguished, youthful supporters.

The PPP, the only party with a significant presence in all provinces, dominated in Sindh as expected, but failed at the national level by losing seats elsewhere. The PTI has not done well in Punjab’s provincial elections, but will be the largest party in the Khyber Paktunkhwa provincial assembly elections, replacing the Awami National Party (ANP). It could form the provincial government, gain experience and showcase its suitability for national governance.

What are the implications of the election, and what does it portend for the future of this nuclear regional power of 180 million people? The election exercise, involving 86 million voters, 15,629 candidates contesting 848 federal and provincial assembly seats, 645,000 polling staff, 600,000 security personnel and 69,801 polling stations, went off well despite the worst pre-election terrorist violence in Pakistan’s history.

The highest-ever turnout of 60 per cent shows the importance voters gave to the elections by defying terror threats. Sadly, some incidents of violence occurred on polling day. The Pakistan Taliban’s selective targeting of progressive parties did not provide them with a level playing field. To an extent, their complaints are justified, but in the case of the PPP, which ruled at the federal level and the ANP, which led the provincial government in Khyber Paktunkhwa, the results reflect the public’s unhappiness with them.

The new factor is the rise of Imran Khan’s PTI as the third force in what used to traditionally be a two-horse race. Imran’s charisma, his reputation untouched by allegations of corruption, a desire for change from 42 years of misrule and support from the educated/liberal circles and youth is clear. So why did the PTI not do even better?

Perhaps Imran did not have the time to put together a nationwide party organisation or to field candidates for every seat in the national and provincial elections.

The youth surge is perhaps the most significant factor in the elections, but with inadequate educational opportunities, joblessness, growth of religious conservatism and lack of cable penetration in the rural areas, the percentage of youth supporting the PTI is more than matched by those supporting the PML(N) and the religious parties.

Punjab, Pakistan’s largest province, has the largest number of seats in the National Assembly and the biggest provincial legislature. Sharif, whose party — with brother Shahbaz Sharif as chief minister — has governed Punjab for the past five years is an old campaigner and his well-oiled party organisation did well.

While their transport projects have taken the limelight, improving the state educational system in Punjab with catalytic support from the UK’s development assistance programme is a noteworthy achievement requiring follow-up and replication elsewhere in Pakistan. Education and infrastructure are key to Pakistan’s progress.

While hoping for an absolute majority in the 272-seat National Assembly, Sharif has invited all parties to work together to face challenges such as the energy crisis and poverty. The reality is that Pakistan will need to be governed by a coalition approach, if not a formal coalition. The PTI will not join Sharif as Imran has made it clear that he will not join either the PPP or the PML (N) as he regards them as birds of a feather. Hence an arrangement will probably be worked out with the PPP.

In any case, the PPP will control Sindh, which cannot be alienated as it is the second-largest province. In Balochistan, the PML (N) is now represented and a coalition will be the outcome. With the PTI as the largest party in Khyber Paktunkhwa, the fact that both the PML(N) and the PTI have similar positions on reaching political rather than military solutions to resolve the Taliban problem should facilitate a working accommodation.

The apprehension of a hung parliament is now over. A strong government which will now emerge, run by capable politicians ready to appoint and be advised by competent bureaucrats of integrity, is well positioned to take back space on foreign policy, security , defence and nuclear policy from the military which had moved into the vacuum created by weak governments and politicians unversed in these crucial issues.

An active opposition in the National Assembly led by Imran will also be a healthy development and accountability check.

To overcome the energy crisis, revive the economy, restore foreign exchange reserves and combat extremism and terrorism, Sharif will need to create national consensus where possible, or at least coalitions of the willing. With that base he will be better poised to tackle issues in external affairs, engage with the US wary of his position on terrorism, improve relations with India without compromising Pakistan’s national interests, and meet the challenge increasingly presented by Afghanistan as the US withdraws.

Sharif has the gravitas and should have learnt from what he has undergone in the last two decades. He also has the PPP’s example before him of the fate of a government that disappoints its electorate.

Ambassador Tariq Osman Hyder is a former Pakistani diplomat.