On foreign policy, Paul is as good as Mitt

He is prone to making tall statements without checking to see if they make sense

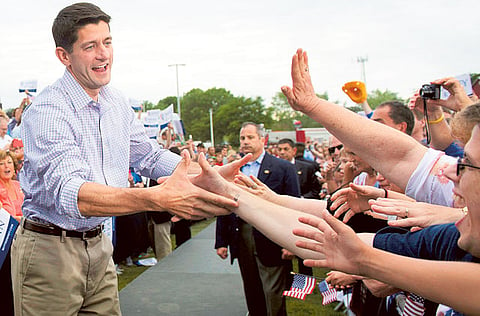

By choosing Paul Ryan as his running mate, Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney has sent out many messages, one of which is that foreign policy will not be a prominent (or, if he can help it, even a visible) element of his campaign.

The few statements that Romney has made have been collages of sheer ignorance: His attacks on President Barack Obama’s new START treaty with Russia, for instance, amount to the most ill-informed articles on arms control that I’ve read in 40 years of following the nuclear debate.

His recent European tour, usually a routine exercise for a presidential aspirant to establish global credentials, proved a disaster from start to finish.

Had he wanted to challenge Obama in this arena, he might have chosen a vice-presidential candidate with a strong foreign policy record, as Obama himself did when he picked Joe Biden. Instead, probably wisely (on political grounds anyway), he pretty much surrendered the realm, as Ryan also appears to know next to nothing about international affairs. Or does he?

Ryan is chairman of the House Budget Committee. National security spending accounts for roughly one-fifth of the federal budget; one might therefore assume that he has some grasp of its dimensions. It also turns out that Ryan delivered a lengthy speech on foreign and defence policy at the Alexander Hamilton Society last June, the opening line of which suggested that he’d mulled over the links between his alleged expertise and the subject at hand.

“Our fiscal policy and our foreign policy are on a collision course,” the address began, “and if we fail to put our budget on a sustainable path, then we are choosing decline as a world power.” An intriguing, if not very original opener — but he took it nowhere. In his speech, Ryan spelled out no path for avoiding this collision, never quite explained why the collision was inevitable, displayed no understanding of the size or contents of the defence budget, and, here and there, recited every vague cliche of George W. Bush’s “freedom agenda” while failing to recognise its contradictions.

It’s true, Ryan was born in 1970. He thus has no personal memory of what was going on then. But he could learn from history books that nearly 400,000 troops were at that point fighting a war in Vietnam, a US-Soviet nuclear arms race was spiralling upward, and a buildup of conventional arms was also getting under way along the East-West German border.

Throughout the Cold War, the US maintained a massive garrison of troops, tanks, artillery, fighter jets, helicopters and much else all across western Europe. Yes, there’s a war on terrorism now, but it’s being waged, for the most part, by small bands of troops and unmanned aerial vehicles.

It would be shocking if defence spending did not consume a smaller share of the budget or gross national product today than it did 20, 30 or 40 years ago. Even so, look at the amount that the US is spending on defence (a figure that Ryan never cites in this speech), and the difference isn’t as large as you’d expect.

At its Cold War peak, in 1985, the US military budget (adjusted for inflation, to make it comparable to today’s dollars) totalled $575 billion. The military budget today: $525 billion — and that’s not including money for operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and other theatres in the war on terror. In other words, Obama’s defence budget (again, not including the direct costs of the war on terror) is just 9 per cent smaller than the budget at its Cold War peak.

Ryan could have noted (but didn’t) that the $400 billion in defence cuts were to be spread out over a 10-year period. Second, while it’s true that the budget came first and the strategy came later, that’s what always happens. That’s the defining nature of strategy; it involves setting priorities and amassing tools of power given a certain set of resources. Without a limit on resources, there is no strategy, there’s only an indiscriminate spending spree. Third, neither in fact nor “in effect” did Obama say that he’d “figure out what those cuts mean for America’s security later.” Throughout 2011, into the start of 2012, Obama, his top White House aides, the secretary of defence (at first Robert Gates, then Leon Panetta), and the entire Joint Chiefs of Staff conducted a joint ‘strategy review’ to set US defence priorities not only for the post-Cold War era, but for the post-Iraq war era as well. During this review, the budget and the strategy were assessed in constant tandem.

Finally, on broader issues of foreign policy, Ryan waxed on about Bush’s “freedom agenda” and the theme of “American exceptionalism”, stating that a “central element of maintaining American leadership is the promotion of our moral principles — consistently and energetically — without being unrealistic about what is possible for us to achieve.”

Some commentators have taken this passage as a sign of Ryan’s wisdom: the embrace of an idealist agenda, tempered by the realism of American limits. It is no such thing. As the rest of the speech reveals, it is more a sign of his failure to think through the implications of the ideas he’s reciting or to grapple with the tensions — between the nation’s ideals and its interests.

On the Arab Spring, Ryan is simply baffling. After hemming and hawing about the uncertain future of these rebellions and their governments, and acknowledging the need for democratic institutions to pave the way to a pluralistic society (and the limits of American ability to shape such things), he concludes, “What we can do is affirm our commitment to democracy in the region by standing in solidarity with our longstanding allies in Israel and our new partners in Iraq.” OK, but it’s not at all clear how doing so will bolster US support for, or otherwise appeal to, the fledgling democrats in Egypt, Tunisia, Syria and elsewhere.

For some time now, Paul Krugman has been blasting away at the widespread notion that Ryan is a “brave” and “serious” thinker on the budget and economics. In fact, Krugman recently wrote “Ryan hasn’t ‘crunched the numbers’; he has just scribbled some stuff down, without checking at all to see if it makes sense.” His plan, Krugman writes, “is just a fantasy, not a serious policy proposal.” The same is true of his “ideas” about foreign and defence policy.

— Washington Post

Fred Kaplan is Slate’s ‘War Stories’ columnist, a fellow at the New America Foundation, and author of the forthcoming book The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War.