No one gets, or should for one moment get, a pass on plagiarism — not even the wife of a presidential nominee whose impulsive bluster as a public speaker, and unfaltering proclivity for fabrication, are by now legion.

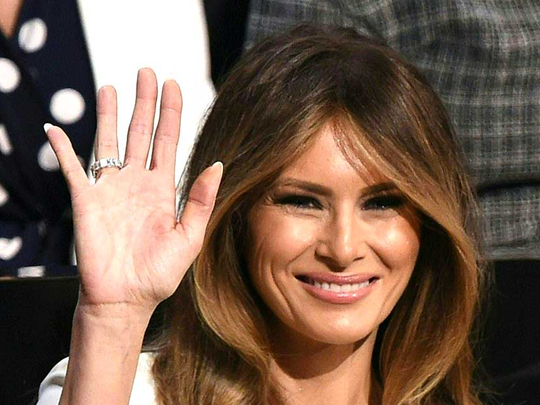

Last week, the wife of Donald Trump, Melania, appeared to believe that she indeed was entitled to that pass, after she took centre stage at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland and delivered a speech that brought conventioneers to their feet. Only it turned out that several portions of that speech were plagiarised unabashedly, in some instances word for word, from the address that in 2008 Michel Obama, then wife of presidential nominee Barack Obama, had delivered at the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado.

There is something innocent, almost child-like, in the spectacle of this 44-year-old model from Slovenia, a non-native speaker of English, composing a speech for delivery at a national convention watched on television by 40 million Americans, seemingly unaware of the serious implications of plagiarism in American culture and of the ease with which, in today’s wired world, a plagiarist can be exposed — and Melania’s indiscretion was raw and brazen.

No one, I say, gets or should get a pass on plagiarism, for it is not, as the saying goes, the sincerest form of flattery. It is outright theft. Lift other people’s work — their ideas, their turn of phrase, their research — and you are taken to task. A student caught in the act will face disciplinary action, perhaps expulsion, by his university. A writer will find his or her books pulled off the shelves at libraries and bookstores. A journalist will get fired, no questions asked, no explanations given and we all know what happened to the likes of Janet Cook at the Washington Post in 1981 and Jayson Blair at the New York Times in 2003.

Academics? Just as equally vulnerable. Consider Stephen Ambrose, the historian and biographer of Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon, who was revealed to have lifted passages without attribution from other historians’ works. The man was left disgraced, not to mention, reportedly with a writer’s block. Remorse — and surely Ambrose felt it — will bring it on.

Notoriety as a plagiarist can effectively doom your reputation, your career, your life. But, let’s face it, there is something seductive about the act of lifting — read, stealing — other people’s work. It is like a disease and no one, not even the high and mighty, is immune from it or is above it, not even celebrated or revered political figures, civil rights leaders, authors and the likes, folks who should know the costs they would incur if exposed.

In 1987, for example, Joe Biden had to drop out of the presidential race after it was revealed that he had appropriated several portions of a speech delivered by the then leader of the British Labor Party, Niel Kinock, without attribution. In 1977, Alex Haley, the African-American author of the ground-breaking book, Roots, was sued by the writer Harold Courtander, who was white, for lifting large chunks of his book, The African. The case was settled out of court and it cost Haley $650,000 (Dh2.39 million), equivalent to $2.4 million today.

Haley never recovered from the shame of being exposed as a disgraced writer who had to acknowledge that a large section of his book (whose adaptation as a TV miniseries mesmerized America at the time), including the plot, main characters, and scores of whole passages were stolen from The African.

And happily, when the Rev. Martin Luther King was found guilty of plagiarising the works of others in his 1955 dissertation, he had been dead for several years. In 1991, a committee of scholars appointed by Boston University found that King, a man of the cloth, was as guilty as sin. “There is no question”, the committee said in a report to the university provost, “but that Dr King plagiarised in the dissertation by appropriating material from sources not explicitly credited in notes”. The Rev. King, whose Ph.D was about conceptions of God by Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman, was nevertheless allowed to keep his degree posthumously.

Back to Melania. The plagiarism in the speech she delivered last Monday at the Republican National Convention should not really be an issue. I, for one, am willing to let this under-educated immigrant from Slovenia off the hook. The story, though most network news outlets were leading with it on Tuesday, is too nebulous to have legs. The issue is rather what the Republican Party at this time in American history has become — a party whose leaders, propelled by populist passions, have polarised Americans by the schisms they continue to insinuate into their political culture and into that culture’s common context and communal sense of reference.

Plagiarism of the kind Melania is guilty of pales when measured against all that. It is the venality and racist rhetoric of a man like Donald Trump that we have to fear, a man who may, just may, occupy the White House in January 2017. And plagiarism, well, maybe it is, after all, the sincerest form of flattery.

Hillary Clinton to Melania: Thanks, dear.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.