What kind of government breaks a promise to give shelter to 3,000 of the most desperate people on Earth, children fleeing war and devastation? What kind of government sneaks out an announcement that the 3,000 places it had reserved for child refugees will be shrunk to 350 and, after that, the doors to that peaceful and prosperous country will be slammed shut? The question is not rhetorical. The first answer is: A government that knows it has the Press on its side. Britain’s Prime Minister Theresa May reckoned she could get away with reneging on her pledge to Alf Dubs — himself a child refugee in 1939 — because the papers have switched sides on the issue, taking much of the public with them.

There was a time, traceable to that photograph of the small, lifeless body of Alan Kurdi washed up on a Mediterranean shore, when these children could expect the sympathy of Britain’s popular Press. In April 2016, even the Daily Mail endorsed the Dubs scheme to give 3,000 a haven in Britain. But then little Alan was erased in the public mind, replaced by images of children who were both alive and bigger, refugees arriving from Calais who the Sun and others believed looked older than 18. The “moral and humanitarian duty” the Mail had spoken of so eloquently was swiftly shrugged off. Refugee children? They’re all scam artists!

Dubs is surely familiar with this kind of thinking. These days, we look back on the Kindertransport — which saved nearly 10,000 Jewish children who, like Dubs, were fleeing the Nazis — as an act of noble British compassion. Compared to today’s miserly numbers, that pride is justified. But it’s worth remembering that the reason children rather than adult Jews were rescued was not only because fewer bureaucratic hurdles were placed in their way.

According to historian Anthony Grenville of the Association of Jewish Refugees, it was also because “small children were easier to get past hostile public opinion”. The government, he told me, “wanted to avoid Daily Mail photographers taking pictures of adults coming down the gangway at Harwich”. (In that same spirit, the Gestapo would closely inspect each Kindertransport train, making sure only children were on board.) Perhaps it’s the hardening of the British heart following those Calais pictures that explains why May felt confident she could break her promise to 3,000 despairing children.

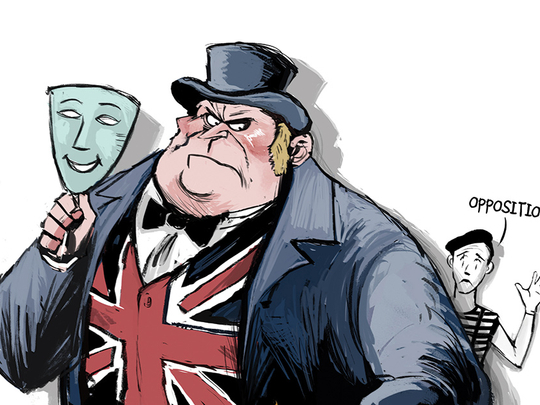

But there is another reason too. For hers is a government that knows it faces no coherent opposition. Note the attention paid to the archbishop of Canterbury — along with a few rebel Conservatives — for speaking out on the Dubs scheme, just as the Speaker, John Bercow, made waves by vowing, successfully, to block United States President Donald Trump from addressing the British parliament. They are stepping into a vacuum where the official opposition should be. The most obvious demonstration — and explanation — of how badly Labour is broken came with last week’s Commons vote on Article 50, triggering Britain’s exit from the European Union (EU). Labour was in pieces on the issue; even the whips defied the whip. Labour proposed a series of amendments, every last one of which was defeated.

And once they had been, Jeremy Corbyn — the Labour Party leader and a man so loyal to his conscience that he rebelled against a Labour government 428 times — led his MPs into the division lobby to vote in lockstep with a Tory government. As one Twitter wit observed, Labour’s position amounted to: “Give us everything we want, and if you don’t, we’ll give you everything you want.” Ah, but what else could Labour do? Surely the party was in an impossible position, torn between MPs representing urban, pro-Remain seats and those whose constituents were strongly for Leave. If the latter group had voted against Article 50, wouldn’t they have been damned for ignoring the referendum and frustrating the will of the people, turning their seats into easy prey for United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip)?

No. There was a way out. Labour could have declared from the start that of course it accepted the June 23, 2016, verdict to leave the EU. That’s what the people voted for. But that’s all they voted for. They did not vote to leave the single market. Indeed, Leave’s loudest voices were adamant that a vote for them did not mean a vote to leave the market. Nigel Farage, the former Ukip leader, regularly extolled the virtues of Norway: Out of the EU, but in the single market.

May’s Lancaster House speech last month gave Labour a huge opening. Once she had committed to taking Britain out of the market, they could have promptly said she had exceeded the referendum mandate. There was a ready-made slogan: “Nobody voted for this.” Framed like that, Labour would have had every right to block the triggering of Article 50. Sure, Brexiteers would have hit back, saying only leaving the single market would allow Britain to reduce free movement. But there would have been plenty of available responses, ranging from “you didn’t say that at the time” to “why assume our talks with the EU will fail before they’ve even started?”.

Such a stance might have been hard for Labour to maintain in government, but in case you haven’t noticed, that is not Labour’s current problem. Instead, all Labour needed was a position that would have kept members and MPs on board and that would have allowed it to present a united front. Then it could have made tactical alliances with the Lib Dems and the Scottish Nationalist Party, forming a coherent bloc that might have attracted anywhere between 15 and 20 Tory Remainers. “They were there for the taking,” says one Labour veteran. This is a government with a wafer-thin majority: As one former Tory cabinet minister told me: “It ought to be doomed to an early death.”

But Labour never got close to making a scratch. I’m told there was not even an attempt at coordination with the pro-Remain parties in the Commons: How could there be, when Labour was all over the place?

Corbyn and his left-wing comrades were so frightened of accusations they were thwarting the people’s will that they ended up as May’s little helpers — aiding and abetting a hard Brexit that could bring ruin. In a tweet both tragic and comic, Corbyn reflected on this disaster with a declaration that the “real fight starts now” — as if the parliamentary decision to trigger Article 50 were a pantomime, and what really matters is waving placards and all the shouting into a megaphone in Hyde Park that now follows. That’s his comfort zone, and he should be allowed to retreat to it. But it leaves the rest of Britons in a zone of discomfort and distress, watching as a government cruel enough to shut out the world’s most helpless children leads the United Kingdom off a cliff, unchecked by an opposition that isn’t worthy of the name.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Jonathan Freedland is a columnist and writer for the Guardian. He is also a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books and presents BBC Radio 4’s contemporary history series, The Long View.