Not lost in translation ...

It is imperative to promote the creative legacy of the Arabic language to non-Arabic speakers and foster an appetite for reading

One of the most captivating aspects about literature is its style. Writers imprint their work with a unique voice. I remember taking part in a quiz where we had to guess the writer from reading just a few sentences. The extracts from Ernest Hemingway, Du Maurier and Charles Dickens were obvious and unmistakable and their ink could come from no other author’s pen.

With each writer, it is not just the story or the characters, but the lilt of the narrator, the scan of the sentence and the creativity of the language that convey an atmosphere that is unique to each author. I grew to love the written word as soon as I could recognise the letters that made them up. To me, as with many, many young readers, books opened up an entirely new world with entirely new possibilities. What I didn’t realise at the time was that there was an almost infinite number of worlds to which I didn’t possess the key.

Whether we speak two, three, five or even ten languages, there is a wealth of world literature that will always be beyond our reach because of the language in which the writer has told his or her story. Unless ...

For native English speakers, some of the best-known and best-loved books have come from foreign tongues. The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Man in the Iron Mask are all schoolboy must-reads — thanks to Alexandre Dumas. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Don Quixote, The Alchemist, Crime and Punishment, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea are just the tips of the iceberg.

Unfortunately, there is a misconception that any book that can be read in English was written in English, despite resounding evidence to the contrary — Stieg Larsson, Miguel de Cervantes, Paulo Coelho, Fyodor Dostoyevsky et al do not roll easily from an English tongue.

Arabic literature has been a source of the most beautiful prose and poetry, but for much of the world, these remain hidden gems. The Arabic language has no Latin roots and is one of the most difficult to interpret for non-Arabs.

Until Egyptian author Najeeb Mahfouz became the first Arab writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988 — his wonderful novels virtually remained a secret to any non-Arabic reader. But with the Nobel Prize, publishers rushed to make his works available to a global audience — allowing us the wonderful chance to read one of the greatest novelists in translation.

Mahfouz was quoted as saying, “The Nobel Prize has given me, for the first time in my life, the feeling that my literature could be appreciated on an international level. The Arab world also won the Nobel with me. I believe that international doors have opened and that, from now on, literate people will consider Arab literature also.”

If we look further back into Mahfouz’s life, his own exposure to the literature of non-Egyptian culture began in his youth with the enthusiastic consumption of western detective stories, Russian classics and such modernist writers as Marcel Proust, Franz Kafka and James Joyce. So literary influences on this Nobel Laureate can be attributed in some part to the literature that was available to him in translation.

At this year’s Emirates Airline Festival of Literature, there was one comment that I felt summed up the power of classical languages in scripts and written dialogue. One Arabic member of the audience, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, said of the excerpts being acted on stage: “Shakespeare in any language is still Shakespeare.”

Later this month, the Emirates Literature Foundation, in partnership with the Executive Council of Dubai, will host the Dubai Translation Conference to celebrate the ideals of the National Reading Law, marking another step towards enriching the quality of Arabic literature. It is imperative to promote the creative legacy of the language to non-Arabic speakers and foster an appetite for reading.

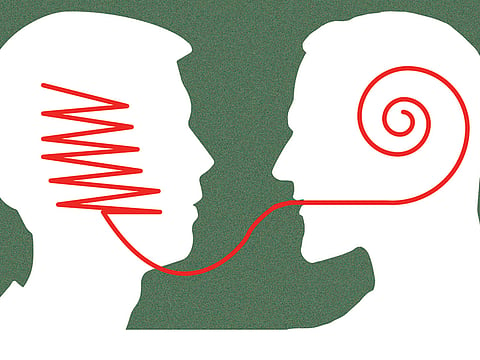

Despite being described as “translation”, there are many authors, journalists and other writing professionals who see the word far beyond the realm of ‘Google Translate’. Their craft is not to research the meaning of one word and replace it with an overseas dictionary definition of another. They are artists and can quite legitimately lay claim — to some extent — to the success of the original author’s work in a foreign market.

In the Middle East, it is called “Arabisation”. It is the skill of conveying meanings without losing messages and portraying content without losing context.

At our first International Translation Conference, we will not only be looking at spreading the Arabic word and translating into English, but also discussing which books are most suitable for translation and — hands up — we will look at those that are simply untranslatable. Any German speakers may well call it “schadenfreude”, the pleasure derived from the misfortune of others. Appropriately enough, it does not have a single word equivalent in any other language.

— Isobel Abulhoul is OBE, CEO and trustee of the Emirates Literature Foundation and director of the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature