We are not always a very united people, us South Africans, despite the hype about our post-apartheid dispensation.

Our divisions racial, economic, spatial and social run deep. Nineteen years after our first democratic election, and a peace that has held despite numerous doomsday predictions, we often fall into the comfort of our divisions.

When one reads in the UK’s Daily Mail that some South African whites believe that a “night of the long knives” (co-ordinated killing of whites by blacks) awaits them on the day Nelson Mandela dies, the reaction is not outrage. We know that such sentiments are common here.

When one hears political leaders who have failed to transform people’s lives despite 19 years in power blame whites for all our current woes without an iota of reflection on their own failings, we do not rush to question them. It is an easy scapegoat. It too has become one of ours.

We are slowly moving closer as a people, after these 19 years, but apartheid urban planning means blacks still live in Soweto and whites in Johannesburg’s northern suburbs, where I gaze out on my garden as I write this piece. The latest census figures released last October (2012) showed that white households earned on an average about six times more a year than black households despite an increase in the average black salary of 169 per cent since 2001. Last Sunday, as I sat watching Manchester City lose 2-0 to local, unfancied side Supersport United, the moaning among many of my black friends was that there so many white people at the stadium. “They only support the English teams, not the local ones,” they complained.

We forgot all this last Thursday. Across the country, on radio and other media, there was no stopping celebrations of Nelson Mandela Day and the outpouring of goodwill towards each other, the poor and the needy. Schools sang Mandela birthday ditties, assemblies were held, politicians elbowed each other out of the way and celebrities cut ribbons at new housing complexes, schools and creches. Ordinary citizens cleaned orphanages and cut grass at police stations. Corporations held out chequebooks.

It was crazy. We know that 67 minutes out of one day does not go that far, but something happens to us here when Mandela is involved. Perhaps it reminds us of that day, way back in 1993, when a rightwinger murdered Chris Hani (at the time arguably the ANC’s most popular leader after Mandela) and Mandela went on television and asked the nation to build peace and walk away from war.

I was 23 then and I remember people my age being so angry that they were talking about nothing else but taking up arms. Mandela pulled an angry, boiling nation back. Looking back, it is almost surreal, the stuff of movies. Mandela’s was a short address that began: “Tonight I am reaching out to every single South African, black and white, from the very depths of my being. A white man, full of prejudice and hate, came to our country and committed a deed so foul that our whole nation now teeters on the brink of disaster.”

His third line turned it around. He referred to the witness to the murder, who had called the police: “A white woman, of Afrikaner origin, risked her life so that we may know, and bring to justice, this assassin.”

The following year, almost to the day, South Africa voted in its first democratic elections. We did not go to war, as many had predicted.

There are other moments like this. The Rugby World Cup of 1995, when he turned a stadium full of rugby jocks into patriots when he wore the Springbok jersey and celebrated victory with the South African team.

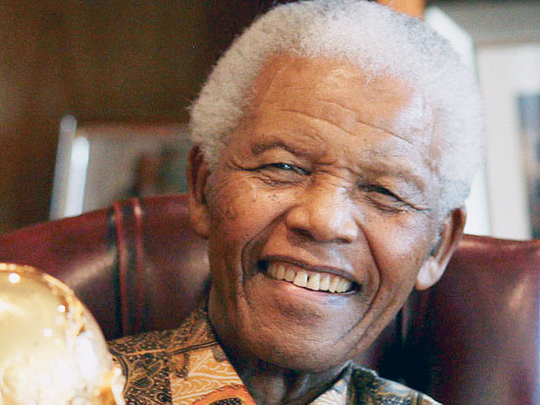

Mandela makes us remember that humanity can be better than much of what we see around us today. Sure, there are elements of Mandela Day which are Disney-esque in the extreme and make you want to squirm. The scandals which have wracked his family these past few months make us all hang our heads in shame.

Yet, amid all the fawning and the gooeyness, amid the scandals and the infighting, something shines through. Mandela is a special man and we are lucky and proud to call him our own, even as the past few weeks of his hospitalisation have reminded us that he will leave us someday soon.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Justice Malala is a political analyst in Johannesburg. He was founding editor of South Africa’s ThisDay newspaper, publisher of the Sowetan and Sunday World, and Sunday Times correspondent in London and New York.