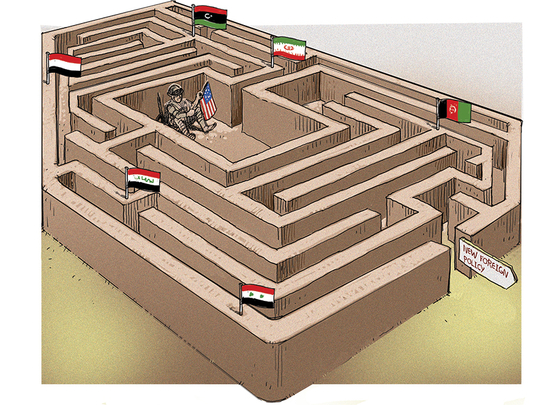

The new United States president will have to make a priority of establishing a new clarity of purpose for American policy in the Middle East instead of the present confusion of opportunistic interventions.

The US is supporting Shiite militias in Iraq, but fighting them in Syria; making war on Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), while largely ignoring the civil wars that allowed Daesh to flourish; and remaining deeply suspicious of Iran while also having eliminated two of its most forceful neighbours and forging a nuclear deal to Tehran’s great advantage. Not to mention Palestine where the administration has successively backed a two-state solution while doing nothing to stop Israel’s slow destruction of Palestine.

The new US secretary of state will need to make a serious effort to win back affection from America’s many would-be friends in the Arab world. This will need the US administration to abandon regime change and instead seek to restore the rule of law and reassert principles such as the inviolability of international borders, the repudiation of the acquisition of territory by war, the establishment of regional security structures and an end to unilateral military interventions.

Such a task is complicated for the US, owing to the loss of its previous domination as the sole superpower, with Russia’s arrival back in the region, as well as the potential arrival of China and maybe even India. But notwithstanding the difficulties, if there is no restart, there is a real danger that the US will continue to be dragged into a series of competing and conflicting wars and fail to support the more important growth of stability, economic prosperity and a strong civil society in the Arab world.

Whoever becomes the new US Secretary of State, he or she will have to look back at what has happened. Successive American-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq destroyed Iran’s most dangerous neighbours in the governments of the Taliban in Afghanistan and former Iraqi president Saddam Hussain in Iraq, and the subsequent chaos of decades of civil wars in both states gave Tehran a huge boost. This was followed by the successful conclusion of a nuclear deal, which allowed Iran to feel even more confidant and coincided with a more vigorous Iranian policy of dangerous regional meddling.

In Iraq, the toppling of Saddam was following by a decade of unplanned direct US rule and a weak Iraqi government as the country disintegrated. In Syria, the failure to enforce America’s own “red lines” helped Syrian President Bashar Al Assad’s regime gain the confidence to expand its brutality leading to the vicious and confused conflict that is destroying the country.

This chaos was to the great benefit of Daesh, which successfully launched the first terrorist state in a territory that spanned large parts of Iraq and Syria and after two-and-a-half years is still resisting the assorted international coalitions arrayed against it.

Sectarian nature of government

The American failure to nurture strong governance in Iraq allowed the Iranians to get their allies’ militias into dominant positions in the south and that raw power has combined with political influence to increase the sectarian nature of the government, despite the US remaining stuck in a close alliance with the government and therefore the Iranian militias. But in Syria, the US is fighting the same militias, as Iran has sent its allies from Hezbollah and its own Revolutionary Guards to fight for Al Assad, where they tipped the balance of power in his favour.

Further confusion dominates US policy in Libya where the Nato-backed operation toppled Muammar Gaddafi and replaced him with a civil war that is still dragging on, with the US supporting the internationally-backed government that has failed to attract any support for the other two governments.

In Yemen, the Saudis are leading the regional coalition, that includes the UAE, to resist Al Houthi rebels and restore legitimate governance and although the US backs the effort, it has done little on the ground to help bring about a quick end to the war.

It may be some consolation in the US State Department that the US is not alone in its confusion, as both Russia and China have deeply inconsistent alliances. Shireen Hunter observes in Lobelog that Russia wants a strategic relationship with Iran while at the same time reaching out to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Arab states. It wants to restore its damaged relations with Turkey while also keeping Al Assad in power. Meanwhile, as China takes the first steps to extend its regional reach, it is also facing similar dilemmas.

It wants to gain influence in Afghanistan, where pro-India sentiments are strong, but it is committed too much to Pakistan. It wants close relations with Iran while it is promoting the Pakistani port of Gwadar against Iran’s Chabahar, as well as seeking long-term access to the Gulf states’ oil.

And, of course, lest we become confused by all this superpower jockeying for access to the Middle East, the Arabs have their own plans and priorities. Given the superpower muddle, they are right to take their future into their own hands, which is the most important lesson for any new US Secretary of State.