“In life, there’s the beginning and the end,” John Carlos, the black American Olympic medallist who raised his fist in a black power salute from the podium of the 1968 Olympic Games, told me. “The beginning don’t matter. The end don’t matter. All that matters is what you do in between — whether you’re prepared to do what it takes to make change. There has to be physical and material sacrifice. When all the dust settles and we’re getting ready to play down for the ninth inning, the greatest reward is to know that you did your job when you were here on the planet.”

As tributes have poured in this week from world leaders and sporting figures, boxing fans and political activists following Muhammad Ali’s death, it’s clear that, from beginning to end, he understood he had a job to do while he was on the planet — inspire people.

And he did it brilliantly. United States President Barack Obama says he kept a pair of Ali’s gloves on display in his study under a picture of Ali towering over Sonny Liston after he knocked him out in the first round of the World Heavyweight title fight in 1965. “Muhammad Ali shook up the world,” said Obama. “And the world is better for it. We are all better for it.”

With former president Bill Clinton scheduled to deliver a eulogy, Ali’s funeral on Friday will in effect become an affair of state. Everyone, from the presumptive Republican nominee, Donald Trump, to the “democratic socialist” hopeful, Bernie Sanders, has lauded him. “When champions win, people carry them off the field on their shoulders,” said the Rev. Jesse Jackson, the civil rights leader and a long-time friend. “When heroes win, people ride on their shoulders. We rode on Muhammad Ali’s shoulders.”

As such, in a moment when America both enjoys a black president and is enveloped by a heightened black consciousness through #BlackLivesMatter, it will bid farewell not just to a man, but a symbol of unapologetic resistance and a radical template for what constitutes black achievement. At a time when black youth are being told that their bad behaviour, not racism, explains their disproportionate criminalisation, here was a black man who never knew his place. He is universally celebrated in death in no small part because he was always larger than life.

Ali’s prowess as a boxer was never in doubt. The way he moved around the ring was a thing of beauty — as though he turned up for an audition of the Soul Train line in boots and gloves. “If karate kicks had been introduced to boxing,” wrote Norman Mailer in The Fight, “Ali would also have been first at that. His credo had to be that nothing in boxing was foreign to him.”

But the widespread adulation that greets his passing stands in stark contrast with his treatment as a pariah both within his sport, by the entire political class after he joined the black separatist Muslim organisation, the Nation of Islam, and then came out against the Vietnam war.

When he announced his membership of the Nation of Islam and that he was changing his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, he told the press: “I’m no troublemaker. I have never been to jail. I have never been to court. I don’t join any integration marches. I don’t pay attention to all those white women who wink at me. I don’t carry signs. A rooster crows only when it sees the light. Put him in the dark and he’ll never crow. I have seen the light and I’m crowing.”

The World Boxing Association suspended him for “conduct detrimental to the best interests of boxing” and unsuccessfully moved to strip him of his title. Promoters recoiled; endorsement offers dried up.

But Ali continued to crow, both playfully, setting his braggadocio to rhyme and his opponents to ridicule, and politically. When it came to Vietnam, he didn’t dodge the draft, he defied it — openly, brazenly — not out of fear of dying for an immoral war, but as an affirmation of his life principles at a time when such opposition was not yet widespread, making the link between racial injustice in America and the imperialist injustice in Vietnam a year before even Martin Luther King would voice his full-throated opposition to the war.

Herein stood the sheer audacity of Ali’s stand at the prime of his career and why his memory — even for those who were not alive when he competed — resonates so widely and so deeply. His stand carried not risk but the certainty of exile from the one way he knew how to make a living — boxing. He could have had anything that America offered a black man by way of riches and fame at the time, and he turned his back on all of it to make a connection between his own freedom and that of the oppressed globally. He was stripped of his title the same day and his licence was suspended.

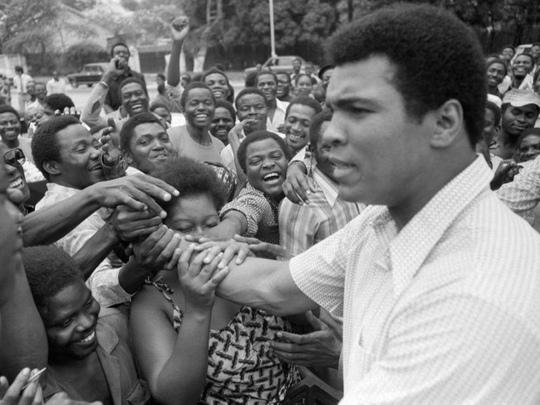

Standing his ground elevated his image internationally. “We knew Muhammad Ali as a boxer, but more importantly for his political stance,” says the artist Malick Bowens in the film When We Were Kings. “When we saw that America was at war with a third-world country in Vietnam and one of the children of the US said, ‘Me? You want me to fight against Vietcong?’ It was extraordinary that in America someone could have taken such a position at that time. He may have lost his title. He may have lost millions of dollars. But that’s where he gained the esteem of millions of Africans.”

But there was nothing inevitable about Ali emerging triumphant, still crowing, laden down with awards and ceremonial pride of place, with a funeral fit for the king that he was.

Esteem does not pay the bills. Nor does it offer any guarantee of readmission to national mythology — particularly for a black sportsman. After his celebrated Olympic victory before Hitler in Berlin, the sprinter Jesse Owens ran a dry-cleaning business, was a gas pump attendant and even raced horses for money and eventually went bankrupt. “People say it was degrading for an Olympic champion to run against a horse,” he said. “But what was I supposed to do? I had four gold medals, but you can’t eat four gold medals.” And Owens never tried to upset the apple cart.

Ali’s return in the 1970s, culminating in winning back his title and the Rumble in the Jungle was like a glorious karmic rebuke to his exile. His global appeal was only enhanced by the international venues that staged his comeback — Kinshasha, in what was then Zaire, for the Rumble in the Jungle, and “the Thrilla in Manila in the Philippines.

Throughout, the most powerful message Ali sent was one of self-definition — a freedom beyond the legal rights and formal equality that had been won as he rose to prominence. The ability to rise above the strictures of race, nation, class and the myriad constraints that regulate our behaviour and take the consequences for living your life as you see fit. “I am America,” he had once said. “I am the part you won’t recognise. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky, my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.”

Ali was a product of his time whose meaning transcended his time; a product of his sport whose significance transcended his sport; a product of his race whose appeal transcended his race. America, in particular, sees him differently now than it did 50 years ago — not simply because the world has changed, but because he did so much to change the world.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Gary Younge, a feature writer and columnist for the Guardian, is the author of No Place Like Home: A Black Briton’s Journey Through the American South, and The Speech: The Story Behind Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s Dream.