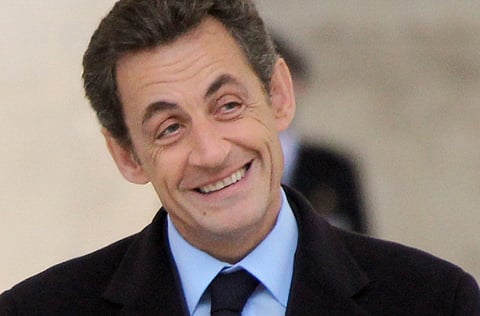

Much ado about Sarkozy

Rumours of extra-marital affairs, low ratings hound the French president

French President Nicolas Sarkozy likes to portray himself as a swashbuckling captain at the helm of le bateau France but even by his standards this is proving a challenge. First came rumours that his ex-supermodel wife Carla Bruni-Sarkozy had run off with a singer and he with a minister. To make matters worse, his right-wing party faces a debacle in regional elections seen as a mid-term litmus test of his popularity.

Halfway through his presidency, the talented Sarkozy remains an oddity to the French — personally and politically. They've had to contend with him becoming the first president to divorce while in office, followed by his whirlwind romance and marriage to an ex-catwalk queen who "finds monogamy boring".

If last week's rumours prove accurate, the electorate may be in for fresh turbulence. Politically, his rhetoric has lurched from near extreme-right to quasi-Che Guevara.

The president is certainly a caricaturist's dream. There is nothing easier than taking a pop at his serial bragging, his slightness next to his towering, femme-fatale wife, his platform shoes and his nervous tics. Few, however, question his dynamism or his bravery.

Strong impression

Sarkozy's alpha-male status was sealed back in 1993 as mayor of Neuilly-sur-Seine, France's richest town. He walked unarmed into a classroom and negotiated the release of dozens of children held hostage by a deranged man wearing an explosive belt. His only fear, he said afterwards, was of "doing a bad job".

Since his election in 2007, he has been at pains to keep up that dynamic image — with some success. France's turn at the six-month rotating European presidency in 2008 was deemed a triumph. He deftly handled the diplomatic repercussions of the Russia-Georgia stand-off that year, brought France fully back into Nato, acted decisively when the financial crisis struck, and was instrumental in creating the G20.

He has kept up a furious pace of reform, brought high-profile left-wingers into his "open" government and recently threw political correctness to the wind by launching a debate on French identity and suggesting a possible ban on burqas. His campaign promises included slashing France's bloated public sector by replacing only half of all retiring civil servants.

So, midway through his five-year term, Sarkozy has set in motion almost 80 per cent of his promised reforms, according to the Brussels-based Thomas More Institute. Impressive, n'est-ce pas?

A growing chorus of critics, however, argues that the result is little more than a "Sarko circus", full of sound and fury. He charges around, they say but, to quote a French expression, "the mountain" invariably "gives birth to a mouse".

In its report, published late last year, the Thomas More Institute says his Bonapartist habit of "advancing on all fronts" has meant many reforms are ill-prepared, and that he is prey to lobbyists. The most glaring recent example was the rejection by France's highest constitutional body of a flagship carbon tax on polluters, which was supposed to seal Sarkozy's green credentials.

The suburban Marshall plan never left the ground. And for all his promises of cost-cutting, state expenditure has been reined in by a modest 7 billion euros (Dh35.38 billion) a year.

In his book, It's Nothing, political commentator Thomas Legrand rejects the idea that the president has changed the face of France. "Perpetual motion has taken the place of action and energy has replaced coherence. Nicolas Sarkozy is a Chirac who sweats."

Slowing down

In an interview in the Le Figaro newspaper, the president indicated that he had received that message. For the first time since taking up office, he announced a "pause" in his exhausting reform drive in 2011, so that those already enacted could be properly followed through.

Perhaps the most slippery facet of ‘Sarkozyism' is its economics. In November, the president announced that "France must cease being the world champion in state spending" the day after announcing a 35-billion-euro "grand loan" for state investment. Right-wing economists question his stomach for tackling chronic deficit and debt.

"I'm not sure Britain would cope with Sarkozy's bling-bling statism for long," says Dominique Moisi, a political analyst. As for the French, "they like the fact that he's so active, but they don't like him".

Polls suggest Sarkozy's UMP party is facing humiliation in regional elections. Today only two regions from the 22 in mainland France are controlled by the right. There is a chance even these may fall, in which case the once indefatigable Sarkozy — who in August had a malaise while jogging may once again start running on empty.