A decade or so ago when George W. Bush was United States president, a consistent critique of American foreign policy was that the US tended to plunge into problems without much forethought — that being seen to do something often seemed to be a greater concern for policymakers than doing the right or smart thing.

Today, the common criticism is that the US is too slow to act, too prone to being careful, often lengthy, deliberation which is sometimes indistinguishable from inaction. Russia’s new, and growing, involvement in Syria is the latest issue to bring this to the fore.

Syria, of course, is the Middle East’s Great Unsolvable Crisis — a civil war whose impact is felt far beyond its own borders, a disaster that cries out for a solution on both the military and humanitarian levels, but for which there are no obvious or realistically achievable answers.

Over the last few weeks many foreign policy strategists in the US have been wondering why Russia would want to get involved in a mess like this in the first place.

Clearly, it is not simply to prop up Moscow’s longtime ally, Syrian President Bashar Al Assad. If that were the main goal, it is difficult to understand why Russia did not either get involved earlier or do so now in a much bigger way.

For US President Barack Obama, however, the immediate question is what, if anything, he should do in response. Many people in Washington, not just the president’s opponents, believe that Russia’s involvement in Syria should serve as the spark for a deeper American commitment to the conflict.

Different view

In his recent interview with CBS News, however, Obama made it clear that he sees the issue quite differently. When the interviewer, Steve Kroft, characterised Russia’s moves into the Middle East as a challenge to US leadership, Obama dismissed the premise of the question.

“If you think that running your economy into the ground,” he said, referring to Russian President Vladimir Putin, “and having to send troops in, in order to prop up your only ally, is leadership, then we’ve got a different definition of leadership”.

At the heart of this debate is a broader, more philosophical question: What role should the US play on the global stage? Also (important in a presidential election season): How involved in the wider world do Americans themselves really want to be?

Among Republicans it is axiomatic that the international community has lost respect for America because the country no longer swaggers on the world stage.

Few GOP candidates have anything good to say about George W. Bush, yet it is clear they all miss his ‘because-I-said-so’ attitude toward foreign policy. Listen to any Republican candidate and the message is basically the same: Obama’s deliberative style has led to a loss of respect for America. Other countries no longer fear the US and, as a result, America no longer automatically gets its way.

Leave aside for a moment whether this was ever really an accurate description of how America functioned in the world, as an ideology it is surprisingly reactive.

The news last week that Russia had begun to bomb targets in Syria was treated in US political circles as a crisis.

Nor is the view that Washington needs to do more confined to Republicans. Last year, Hillary Clinton criticised her former boss, telling an interviewer: “Great nations need organising principles, and ‘Don’t do stupid stuff’ is not an organising principle.”

Since leaving office three years ago Hillary has quietly but firmly put out the word that she advocated for a more activist US approach to Syria.

When asked at a recent news conference to comment on Hillary’s more recent criticism of his Syria policy, in particular his reluctance to impose a no-fly zone over that country, Obama said: “Hillary Clinton is not half-baked in her approach to these problems ... But I also think that there’s a difference between running for president and being president and the decisions that are being made and the discussions that I’m having with the Joint Chiefs have become much more specific and require, I think, a different kind of judgement.”

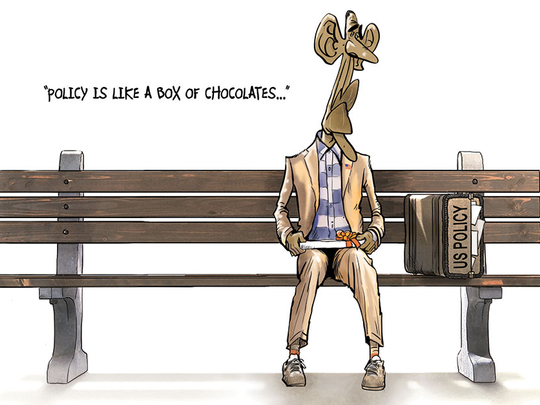

Which brings us back to the original question: How does one avoid the temptations of both action for its own sake and of using thoughtfulness and care as excuses for doing nothing? The burden of being a global power is that it requires a country to have a policy on literally everything.

Obama won the presidency in part because the country was tired of a president for whom swagger often seemed to be a policy all by itself. People liked the idea of a more cautious figure in the White House, with a more deliberative approach to global affairs.

Neither Obama nor anyone else is going to get that balance right all the time, but frustration with the results doesn’t change the fact that America does better with a foreign policy built on persuasion. The careful approach will always have much to recommend it.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches Political Science at the University of Vermont.