Claiming that the military campaign in Syria had “achieved most of its objectives”, Russian President Vladimir Putin decided last week to withdraw the bulk of his air force from Syria; leaving many to wonder about the true motives behind his unexpected move. Although he denied that the withdrawal of Russian forces was a measure aimed at pressurising Syrian President Bashar Al Assad into more forthcoming attitude concerning the Geneva peace process, the Kremlin press spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, did point out that Russia’s immediate aims in the Syrian conflict at this stage requires “intensifying [Russian] efforts to achieve a settlement in Syria”.

When Russia launched its military campaign in Syria last September, the official reason given for the intervention was to break the backbone of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) before it could “strike at Russia” — a reasonable proposition given that hundreds of Russian nationals have reportedly joined the group. Yet, the course of the Russian campaign shows that the real objective was to address the balance of power on the ground; which had largely tilted in favour of the opposition around the summer of 2015.

While trying to drive back the Syrian opposition, the Russians sought to resume political efforts to solve the conflict. The aim here was two-fold: Prevent any possibility of becoming embroiled in a war of attrition; and secure channels of communication with the United States. Establishing cooperation with Washington over Syria would grant Moscow a place as a key partner in any wider Middle East arrangements. Indeed, the Vienna peace talks for Syria were launched within a month of Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian conflict. Multilateral negotiations rapidly evolved into bilateral talks between the US and Russia, which saw all of the other parties sidelined — including the major European powers and Iran. In fact, Russia had previously insisted on Tehran being involved in any peace settlement over Syria.

Joint US-Russian efforts resulted in the adoption of United Nations Security Council resolution 2254, which included a roadmap to resolve the Syrian conflict. The resolution called for the establishment of a non-sectarian governing body; a ceasefire/cessation of hostilities; an amendment of the Syrian constitution; and the holding of UN-supervised elections within 18 months of the ceasefire.

On February 11, 2016, during the Munich Security Conference, Russian and US representatives reached an agreement on the cessation of hostilities. The final details covering the scope of the ceasefire and, in particular, those opposition groups that would not be covered by its terms, were ironed out in a phone conversation between US President Barack Obama and Putin on February 22, paving the way for the ceasefire to take effect on February 27. Notwithstanding multiple major infractions, the ceasefire has largely held in the days since, reflecting Russia’s increasing interest in solving the Syrian conflict.

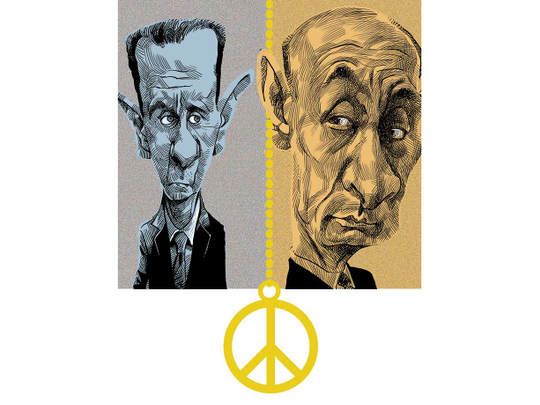

Hence, the decision to partially withdraw from Syria came on the eve of the second round of Geneva peace talks on March 14. The way Putin chose to inform Al Assad of his decision revealed Moscow’s discontent with the Syrian regime’s indifference to the US-Russian roadmap to peace in Syria.

In fact, differences between Moscow and Al Assad broke into the open in recent weeks. Russia’s UN ambassador, Vitaly Churkin, criticised Al Assad’s statement that he would try to “reclaim every inch of territory he lost during the past five years of conflict”. Russia “has invested very seriously in this crisis, politically, diplomatically and now also in the military sense. Therefore, we would like Mr Bashar Al Assad to take that into account”, Churkin said. Moscow was also unhappy with the Syrian regime’s unilateral decision to hold parliamentary elections in April 2016. An unnamed Russian official was quoted as saying, “this announcement goes against UNSC 2254, which envisages all elections be part of a final resolution of the Syrian crisis”.

Combined, these developments suggest that Putin’s decision to partially withdraw Russian forces from Syria on the eve of the Geneva talks was a consequence of growing discrepancies with his Syrian protege. The Russian move, many hope, will make Al Assad more amenable to open and serious negotiations at Geneva. Although very few expect immediate results from the present round of negotiations, it is clear that an international consensus on the need to end the conflict in Syria is emerging. Such international resolve was the crucial factor missing from previous rounds of negotiations. Furthermore, the determination of the world community to resolve the five-year old Syrian crisis through political and diplomatic means will build momentum for the next round of negotiations which will take place around mid-April, time which will be useful to further understand Russian aims and motivations, as well as the nature of the secret deals that Moscow has arrived at, along with the Washington.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is a Syrian academic and writer.