Ali Shamkhani, the head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, visited Moscow a few days ago, ostensibly to continue his talks with Russian officials about the “War for Syria”. As the designated Iranian interlocutor who is empowered to coordinate his country’s policy with Moscow, Shamkhani is presumably anxious to find or accelerate a political solution, now that everyone conceded there would be no military solution to the conflict. Will casualty levels reach the “million” figure before the international community musters the courage to reach an accord? Can Tehran alter its outlook and, equally important, will the next American administration adjust its policy towards Damascus?

Notwithstanding Shamkhani’s visit, and the broader reshuffling in Tehran as the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs Javad Zarif replaced Hussain Amir Abdollahian as his deputy for Arab affairs with Hossain Jabari, little is likely to occur for the balance of the year as the world awaits the results of the presidential elections in the United States. Abdollahian, whose very close ties with the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps — the super hawkish body that steers Tehran’s military campaigns throughout the Arab world — shaped Iranian policy, was muzzled. Jabari, a man who expressed reservations about his country’s Syria policy may have a different outlook, although everyone understands that the sole decision-maker in Iran is the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and he is inflexible. That will not change.

Still, it is entirely possible that Shamkhani’s conversations with the Russians aim to prepare for a potential political transition in Syria, where Iran can position itself as a key player and not become a spoiler during various negotiations. Indeed, Tehran is anxious to clean its soiled reputation and reintegrate into the international community, even if the process may be hazardous, as long as it promotes armed militias and supports terrorist groups. How fast it moves along those tracks is impossible to know, though all are clearly doable.

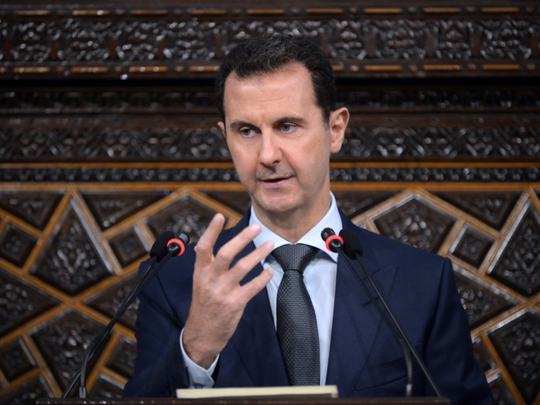

Equally important are the changes that are likely to occur in Washington. Should Hillary Clinton win the US presidency in November, Michele Flournoy, Hillary’s likely secretary of defence may well be entrusted with the Syria file, which could mean fresh US military deployments to push President Bashar Al Assad from power.

Flournoy, who heads the Centre for a New American Security (CNAS) think-tank, said “limited military coercion” might be necessary to drive Al Assad out. Among several recommendations made in ‘Defeating the Islamic State: A Bottom-Up Approach’, the CNAS report she helped produce, one called to widen American goals in the Syrian war, including “arming and training local groups that are acceptable to the United States, regardless of whether they are fighting Syrian President Bashar Al Assad or [Daesh]”. This approach differs from the Barack Obama administration’s preferences, which demand that Syrian revolutionary forces pledge to only fight Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) — in exchange for US support.

In fact, the Obama administration rejected various military options since 2011, presumably because the creation of no-fly zones, targeted strikes or other military options did not promote US interests or to even promise to stabilise Syria. Obama concluded some time ago that his sole objective was to increase pressure on Al Assad that would, in turn, make him more amenable to a negotiated solution. Of course, the American commander-in-chief misread his Syrian counterpart, as Al Assad dismissed a negotiated solution, much less a voluntary departure from the scene, something that serious analysts understood quite well. Simply stated, and even at his worse moments, Al Assad publicly repeated that he intended to die in Syria and that he would never leave. No ifs and or buts about it.

To be sure, Russian and Iranian resolve to help Al Assad prevail effectively means that the war for Syria will continue for the foreseeable future, and that there will be no regime change anytime soon.

Obama, along with much of the US, made his choice not to fight. Despite Flournoy’s pre-election prognostications, Hillary Clinton is unlikely to change course either, though she may bargain with Moscow on the best means to end this tragedy — something that Obama and Russian President Vladimir Putin seem incapable of doing for personal reasons.

For now, few ought to expect the US to forsake Syria or admit failure, though the 51 mid-level Department of State officers — who recently wrote a dissent cable that advocated the use of force against the Syrian regime — believed the time was long overdue to change policy. Regrettably — and at a time when conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Libya and elsewhere amply illustrate — what motivates global powers is risk management, not necessarily conflict resolution. In 2021, on the 10th anniversary of the war for Syria, many will look back at the sheer destruction, including upwards of a million dead, and wonder why such mayhem was tolerated.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of the just-published From Alliance to Union: Challenges Facing Gulf Cooperation Council States in the Twenty-First Century (Sussex: 2016).