Modi needs a new strategy in India

Premier needs to refocus his energies on using all instruments available to him outside Parliament. That means proceeding much more rapidly on two parallel tracks — in Delhi and in state capitals

An important parliamentary session in India — one that gets its name from the country’s monsoon rainfall season — is set to be a total washout. The session, which ends next week, has been disrupted, stalled and otherwise rendered non-functional by parties opposed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government. They’re insisting Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj and two state chief ministers who belong to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party resign on charges ranging from minor misdemeanours to serious corruption. Modi and the BJP have flatly refused.

To be fair, in India’s federal system, the fate of state chief ministers doesn’t lie in Modi’s hands. Swaraj is accused of a relatively minor transgression: enabling a fugitive Indian tycoon to obtain travel documents. And the opposition Congress Party can be accused of using only barely legitimate tactics — the speaker of Parliament has suspended 25 Congress legislators for unruly behaviour — to block a party which has six times as many seats in India’s lower house from enacting legislation.

Regardless, the reality is this: Modi’s government looks unlikely to be able to pass crucial economic legislation — including an amended land acquisition law and a new goods-and- services tax — anytime soon. The delays will have serious repercussions on India’s economy.

It’s Modi’s job to find a way out of this impasse before Parliament’s next session. In the meantime, he needs to refocus his energies on using all instruments available to him outside Parliament. That means proceeding much more rapidly on two parallel tracks — in Delhi and in state capitals.

The most crucial task before the government, for instance — ramping up infrastructure spending — doesn’t entirely depend on Parliament. It requires executive action and faster implementation.

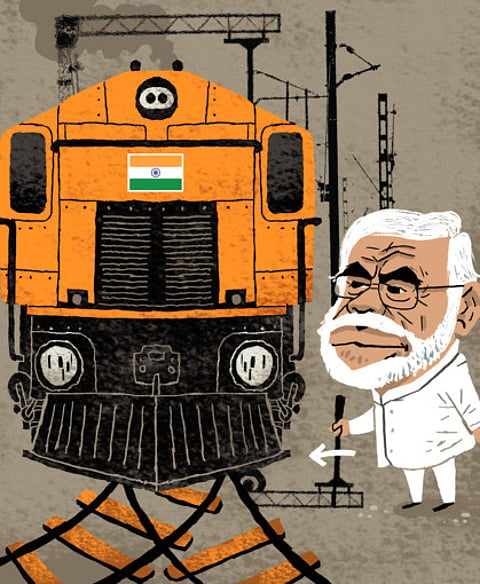

Consider the railways. The government-owned sector is hungry for investment. The railways ministry doesn’t need Parliament’s nod to lay new tracks (the amount of new land required for this is limited), to lease out stations to private- sector players for redevelopment, to introduce new and faster trains or to invest in better passenger amenities. Yet the ministry and its top bureaucrats have hardly set a scorching pace: Their preferred approach seems to be to appoint committees and await the recommendations before proceeding.

While the government has displayed greater energy in building new roads and highways, decisive executive action could speed up construction even more. Privatising India’s stagnant and inefficient ports would require legislation. But that doesn’t mean the government couldn’t restructure their management. Most of India’s major government-owned ports are organised as trusts. If they were converted into companies instead, they would be better placed to raise finance from the markets and monetise their most substantial asset — land. That would bring in much needed investment to boost standards and infrastructure.

At the same time, crucial areas of reform — whether in education, health, skills, farming, rural roads, irrigation, even land and labour laws — largely remain the domain of state governments. While Modi can’t simply issue orders to the states, he can use two avenues to influence them.

First, several of the biggest states are run by chief ministers from his own party or his alliance. Most of them preside over single-party governments that can pass legislation easily. They could give their local economies a huge boost by pushing ahead with investment-friendly, consumer-friendly policies. Rajasthan, a BJP-ruled state in western India, has already implemented several such policies, including new labour laws. States that host more established manufacturing sectors may be more reluctant to introduce such reforms. But hopefully if investment begins to flow to Rajasthan as expected, they’ll fall into line.

The second avenue is the government’s NITI Aayog — a policy commission that replaced the erstwhile Planning Commission. Modi chairs the commission and uses it as a forum where the central government interacts directly with all 29 chief ministers. He can use NITI Aayog to help states create templates for smarter governance, including on contentious issues such as land. After all, non-BJP states also have great incentive to come up with productive policies: Indian voters re-elect governments that deliver even a modicum of good governance. And if more states grow, India will grow.

Ultimately, the only way for Modi to counter the opposition’s obstructionist strategies is to ensure that he continues to execute policies that boost India’s economy. Otherwise, when he seeks a second term in 2019, he too may be washed away.

— Washington Post

Dhiraj Nayyar is a journalist in New Delhi.