Germany looks uncomfortable with the unasked-for mantle of European leadership. Berlin was not the only villain during the Greek euro crisis, but it often seemed so to the rest of the world. Most saw a hapless Greek government humiliated by Teutonic bullying. Perceptions, as well as rules, count for something in international relations.

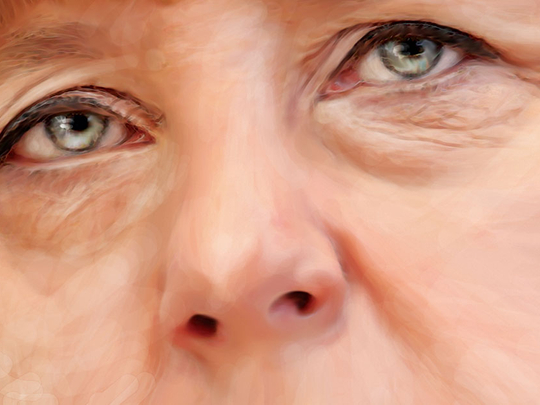

Now, though, German Chancellor Angela Merkel is getting it right. For the most part, the refugee crisis has shown Europe at its worst: Lofty rhetoric about collective action gainsayed by a fearful retreat into the narrowest of nationalisms. There have been exceptions. Sweden has been generous to a fault. And the German chancellor has shown she can grasp the other side of leadership.

For the past several years, Europe has kidded itself that it can shut out the world. Syria was someone else’s problem — and, anyway, America’s fault for invading Iraq. Any obligation to Libya ended with the removal of Muammar Gaddafi. The rich nations of the European Union (EU) had other things on their mind: Austerity, recession and the never-solved euro crisis. The victims of Bashar Al Assad’s Syrian regime or Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant)? Well, they could stay in camps in Jordan and Turkey.

The hundreds of thousands of Syrians, Iraqis and Eritreans fleeing death and persecution to cross into Europe in the largest movement of people the continent has seen since 1945 have shattered such illusions. Along the way, they have exposed a hollowness in the commitment to collective action — to solidarity, if you like — that, along with the euro’s travails, could yet foreshadow the unravelling of the EU enterprise. The moral imperative to offer succour to the wretched victims of war and terror speaks for itself. But there is also the matter of self-interest. Europeans wrote the international conventions meant to uphold human rights. Shorn of a shared allegiance to the universal values of freedom and security, the EU is nothing.

Merkel has been among the few ready to speak out about Europe’s obligations to the newcomers. My German friends tell me that, cautious as ever, she waited to catch the mood of her compatriots — the volunteers manning reception centres in North Rhine-Westphalia and the football fans waving welcoming banners. Never mind. She has understood what has to be done.

The very worst of Europe has been seen in Viktor Orban, the pocket-Putin who serves as Hungary’s Prime Minister. Ignorant of history, Orban sees the refugees as a threat to European civilisation. His answer is to build a 175km razor-wire fence. Sadly, he is not alone in such bigotry. The Slovak government says it will accept only non-Muslim refugees. There is something truly dispiriting about former Communist states recently welcomed into the EU slamming the door against refugees from other forms of tyranny.

At the other edge of the continent, Prime Minister David Cameron’s British government has scarcely shown itself in a better light. Cameron — driven to panic by a few thousand people camped across the channel in Calais — talked of “swarms” of migrants seeking to “break into Britain”. [On Friday, however, he said that Britain would welcome “thousands more” Syrian refugees ].

National mood

Cameron’s earlier indifference to images of corpses asphyxiated in the back of a truck in Austria or to the body of a young child washed ashore on a Turkish beach misreads Britain’s national mood. Ordinary Brits see the difference between desperate refugees and economic migrants more clearly than a leader living in fear of being outflanked by xenophobes.

Others in Europe also talk of the need to uphold “sovereignty” over their borders. Yet, it is obvious to anyone who thinks about it that such sovereignty is another of those illusions. No single nation can hermetically seal its borders against the turmoil beyond.

Responding to the crisis demands organisation and resources. The scale and speed of the movement would have overwhelmed even a well-prepared EU. The Schengen system of open borders has buckled under the strain. So too has the so-called Dublin convention, which says that asylum seekers must be registered at their first point of entry to the EU. What is needed now is a rigorous, well funded EU-wide system that offers succour to refugees while clamping down on people traffickers and applying manageable limits to the numbers of other migrants.

The imperative is leadership that understands that solidarity in such circumstances is not just some vague sentiment beloved of Europhiles or, for that matter, simply the compassionate and decent response to such terrible human misery. It is also the only practical answer. A large, rich and ageing continent can easily absorb such newcomers and, over time, will profit greatly from their energy and enterprise. But the initial dislocation must be equitably shared. Merkel has shown such leadership. We must hope that others are shamed into following.

— Financial Times