In foreign affairs, symbolism matters. British Prime Minister Theresa May’s arrival at the White House last Friday as the first foreign leader to visit United States President Donald Trump sends a clear message to the world about the intimacy of the ties between London and Washington DC. It also shows that Britain’s sometimes-derided diplomats have done their job well and puts to bed the idea that the former leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party, Nigel Farage, or anyone else was needed as a go-between.

May will now be fresh from addressing congressional Republicans — another privilege that would be accorded to few other foreigners — and I predict she will get on well with Trump, even though their personal traits are as different as is possible among members of the same species. Try to imagine the British PM sending out angry tweets at three in the morning, or savaging Britain’s own intelligence agencies. Picture Trump reading files quietly for hours, then asking for more information and refusing to give any commentary on his thoughts. Both defy the imagination. It is the greatest contrast in styles between the holders of these offices, at least since Ulysses S. Grant overlapped with William Gladstone — and they didn’t have to meet.

Yet, Trump evidently is predisposed to find his “Maggie” and he will probably warm to her clarity and firmness. For her part, May is highly skilled at creating a warm relationship with colleagues when she really wants to, and never in her life will she have been more determined to do so than last Friday. She knows, as does anyone who has seen government in Britain from the inside at the top, that leaving the European Union (EU) is a risk, but estrangement from the US would be a certain disaster.

United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent may be the subject of controversy this week, but Britain only has missiles that work at all because America is happy to sell them to the UK — something it does for no one else. Britain’s ability to detect potential terrorist attacks is as strong as it is because British security and intelligence-gathering are tightly integrated with the US. Every day, all over the world, whatever Britain’s ambassadors and soldiers are doing, they are usually doing it in concert with their transatlantic cousins. And Britain’s business with America is greater than that with any other single country, even before attempting a special trade deal. The alliance with the US is the one relationship the UK has that is truly indispensable.

Since 1941, British PMs have generally maintained their influence over the policies of US presidents by differing only behind the scenes and giving support whenever it mattered. Sir Winston Churchill bowed to Franklin Roosevelt in accepting what he disliked in the post-war division of Europe; Tony Blair enthused about removing Saddam Hussain to be the most influential ally of George W. Bush. All have sought to avoid the fate of Anthony Eden over Suez, exposed and humiliated after being abandoned by Dwight D. Eisenhower. They have been helped by the fact that, ever since Pearl Harbor, the strategic thinking of Britain and America has usually been in natural alignment.

But in the Trump administration, May faces something no other recent predecessor has encountered in the White House: A different world view, a contrasting approach to a wide range of issues and a potentially serious divide on matters of fundamental importance. Her first priority has to be to persuade and influence the US president on those subjects on which he and his embryonic cabinet have not expressed a settled view. It is not at all clear, from their comments in recent weeks, what price they are prepared to pay for improved relations with Russia, or if they will ditch the nuclear deal with Iran. As they get to grips with these issues, forceful arguments from the British prime minister can make a difference, before major mistakes are made. For if Trump gives Russian President Vladimir Putin the cover to divide and intimidate Europe, or provokes a nuclear arms race in the Middle East, the security of all western nations will be seriously damaged.

The trickiest task of all, however, is to exercise that influence — and push for a US-UK bilateral trade agreement — while creating the space for public differences on other issues. This requires a recasting of the normal rules of how London and Washington work together. For instance, May has rightly dedicated herself and Britain to championing global free trade. That is something Trump is determined to destroy. A new understanding is needed that Britain will differ on this issue, without recrimination or accusation of betrayal.

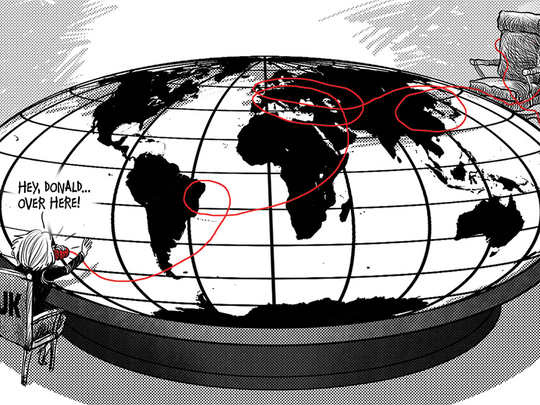

If trade were the only such difficulty, a vast and crucial matter though it is, this problem would be manageable without immense difficulty. But on a wide range of other matters, the “America First” philosophy reiterated in Trump’s inauguration speech threatens to open a split with long-standing allies. In particular, all the signs are that Trump and his advisers are set on a path of confronting the growth of Chinese power.

May is not exactly a starry-eyed fan of China, whether for its political system or its territorial claims against other Pacific nations. But she and most global leaders will doubt the wisdom of tearing up the main areas of cooperation between the US and China, such as on climate change and trade, abandoning the foundations of the West’s relationship with Beijing reached by former US president Richard Nixon in 1972, and intensifying rivalry across the board. Over the coming months, such differences may become very stark indeed. The necessary recasting of the special relationship will have to permit a wider divergence between British and American leaders on some major issues than most of us have known in our lifetimes.

That, like all problems between friends, is best explained early on to avoid resentment later. The British PM and the US president both need to show they can work together. If she influences him on some of these vital issues, both will get credit — her for persuading and him for listening. And in addition, as they contemplate the vastness of our common interests and heritage, they should quietly promise to avoid attacks on each other and their respective countries when they inevitably disagree. For they are now the custodians of a friendship between nations that is beyond price. In this volatile century, it will most certainly be needed again.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

William Hague is a former British foreign secretary and was Conservative party leader when the euro was introduced.