May has called a snap general election. What happens next?

The British prime minister goes to the country on June 8 hoping to strengthen the Conservative majority

Zoe Williams: We need to cooperate, work with unfamiliar allies

The vital thing about this election is that we don’t approach it like a regular election. The timescale, the process, the atmosphere, the challenges, the stakes, the personalities, the possible range of outcomes, all the territory is new. I used to think all elections felt distinctive and special, in a bad way — especially difficult, with particularly negative potential. That was because I’d never encountered a situation like this one.

Anyone on the progressive side, who opposes cliff-edge Brexit and unending Tory dominance, and approaches this in the regular way is going to lose. Scoring points off May’s government is both too easy — they are barely holding it together by any normal governmental standards — and too hard; the levers by which they are held to account aren’t working, and attacks do nothing to douse their impunity. Attempts to drum up support for one party, then jealously guard it from encroachment by a similar party, are a waste of energy. Even if it’s sometimes a pinch to see it, the Tories and Ukip are on one side, and everybody else is on the other; we need to cooperate, cede to a stronger progressive candidate where there obviously is one, work with unfamiliar allies, think strategically about what’s winnable and what isn’t, and make a progressive alliance an electoral reality.

Compass has the data on the seats worth contesting, and will map the war zone within the week. It, along with Crowdpac, Something New, More United and others have the online platforms to raise money and get involved. Political insiders find it hard to adapt and be agile; they need more than the energy of the grassroots, they need its leadership.

— Zoe Williams is a Guardian columnist

Matthew d’Ancona: Feeling sorry for Jeremy Corbyn

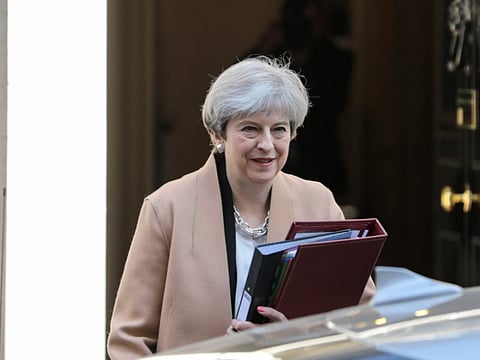

Theresa May’s statement was striking for many reasons but two stand out. First, that she spoke so readily in the first person, as if to leave no room for doubt that this early general election will be about her personal authority at home and in negotiations with the EU.

Second, she claimed more than once that she had made the decision “reluctantly”. This will do nothing to diminish the raging allegations of the opposition parties that this is a nakedly political, deeply cynical U-turn. But I believe her claims to be true.

Spontaneity is simply absent from this prime minister’s DNA. She likes what her aides call “consultative and deliberative” politics: organised processes, timetables, patient evaluation. She has nothing but distaste for those who busk it, who prefer to swashbuckle their way through Westminster and Whitehall instead of doing their homework and taking their time.

So it will have required much persuasion to get her to this point. But there are times when inexorable logic defeats the best-laid plans of mice and Mays. Labour’s position in the polls is historically dire. The Tories are governing with a dangerously slender majority, a weak position from which to be negotiating with our 27 soon-to-be-ex EU partners. If not now, when?

A snap election resulting — May hopes — in a stronger Tory government and an unambiguous personal mandate is self-evidently the smart option. Such a victory would kill off the idea of a second referendum, and close down the argument that the electorate had not given consent to withdrawal from the single market. This will be a verdict on May, her version of Brexit and her vision for the country. I never thought that I would feel sorry for Jeremy Corbyn, but today I do.

— Matthew d’Ancona writes a weekly column for the Guardian. He was previously editor of the Spectator and also writes for the Evening Standard and GQ

Martin Kettle: May has trashed her own brand

Theresa May in Downing Street sounded like Turkey’s authoritarian president Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Give me the unfettered authority to secure the Brexit I want, she said. Any attempt to stand in my way is disruptive and frivolous. So give me the power to act in the name of the people against parliament’s interference. It’s not a nice parallel. May has trashed her own brand.

May has acted like a prime minister who can call an election. But there’s a small but significant problem with that. She can’t. She is subject to the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, passed by the coalition. This means that she needs parliament to vote for a dissolution tomorrow by a two-thirds majority. This in turns means that the opposition parties can still stop the election if they want to.

But it won’t happen. The Liberal Democrats, with only nine MPs, will vote for the election in the hope of getting a bigger Westminster base. The SNP will want an election too. Labour’s position is crucial. But since Jeremy Corbyn put his party on election footing last September he will be hard put to oppose it, whatever the damage the election does to Labour.

One final point. An election on June 8 will be an election on the existing boundaries, with 650 MPs due to be returned until, in principle, 2022. One of the minor effects of this decision is that all the talk of deselection among Tory and Labour MPs is dead, at a stroke.

— Martin Kettle is an associate editor of the Guardian and writes on British, European and American politics, as well as the media, law and music

Sonia Sodha: This is a decision made in May’s own political interest, not in the interests of the country

Despite the countless protests we’ve heard from Theresa May since last summer that there would be no early election, perhaps the real surprise is how long it’s taken her to make this call. The deeper we go into her premiership, the trickier things will become. There are economic headwinds looming: we’re likely to see inflation and the cost of living continue to rise, dampening wages. Hospitals will continue to struggle to cope with increasing demand, and we’ll see more stories about schools in Conservative constituencies considering drastic solutions like opening for four days a week as a result of budget cuts. And the longer Brexit talks go on, the more vulnerable she’ll be to hardline Euro-sceptics from her party saying she hasn’t delivered. The prime minister has just bought herself an extra two years before the country will be asked to deliver a verdict on the Brexit she’s negotiated.

But make no mistake, this is a decision made in her own political interest, not in the interests of the country. May has faced little real opposition from a Labour Party that’s been languishing in the polls in recent months. The only grim question facing the Labour Party is how many seats will it lose? And where will that leave Jeremy Corbyn? Will he resign, or choose to cling on against the odds as he has done in the past?

One thing is clear, this election certainly won’t deliver a clear mandate on various options for Brexit: it can’t when the main choice people face is between a Conservative prime minister talking up a hard Brexit, and a Labour Party that’s completely split on the issue. The election campaign will no doubt be dominated by the divisive political rhetoric of recent months. I can barely wait.

— Sonia Sodha is chief leader writer at the Observer

Simon Jenkins: For Labour the news is nothing but good

Normally a prime minister’s case for another election within two years of receiving a working majority is weak. In Theresa May’s case it has become increasingly strong. Her government is dominated by Brexit. The phase of hard-Brexit grandstanding is clearly coming to an end, and the more delicate phase of compromise is starting. Reality will be “softening” Brexit by the month.

The Tories’ hard-Brexit backwoodsmen thus stand poised to undermine May’s team. Parliamentary spoilers will be looking over the negotiations by the day. May cannot rely on the support of an opposition in disarray and risks constant disruption to her tactics. She will need all the loyalist support she can muster. To this is added her undoubted weakness in lacking a personal mandate for personal policies, such as on grammar schools, which are already costing her party support.

Were an election unlikely to improve May’s slim majority, going to the country might seem reckless. With a poll lead which, at the weekend, was hovering round 20 per cent, an election is more than appealing. It would seem reckless to reject it. While the public response to a third national vote in two years will be a groan, at least the campaign will be short.

For Labour the news is nothing but good. An election under Jeremy Corbyn is certain to be painful. But by autumn its sad flirtation with the archaic left should be over. A new era under a new leader can dawn.

— Simon Jenkins is a journalist and author. He has edited the Times and the London Evening Standard

Ruth Wishart: A snap election raises questions for all the Scottish parties, though very different ones

The SNP, having formally demanded a second referendum, will find it difficult to produce a manifesto which does not make that its central plank. Failure to do so would disappoint its core support, although the party so recently said the ideal timing for indyref2 (second independence referendum) would not be until the shape of the Brexit negotiations was known.

But another general election might give them majority rather than minority government in Holyrood.

The prospect of another general election will hardly be greeted with enthusiasm by the Scottish Labour Party, having slipped to third place, and boasting just one Westminster MP. Added to which there are real tensions between its leader, Kezia Dugdale, and Jeremy Corbyn, whom she didn’t support in the leadership election. There is tension too between her and her own deputy Alex Rowley, who is more relaxed about independence.

The Scottish Tory party finds itself in the unusual position of being the second largest force in Scotland at the moment, and its leader, Ruth Davidson, has gained a good press, especially in England. But her recent support of the “rape clause” in welfare cuts has attracted across the board dismay. And the Scottish Lib Dems are barely polling more than the Greens at the moment — setting their face firmly against independence has not played well with their “nationalist” wing. Ukip has never been a force in Scotland running at around 2 per cent. Its solitary representative is MEP David Coburn, a household name only in his own house.

But from a Scottish perspective this now has the appearance of a bizarre game of high stakes poker between mesdames May and Sturgeon.

— Ruth Wishart is a Scottish freelance columnist and broadcaster, who has spoken in favour of Scottish independence.

— Guardian News and Media Ltd