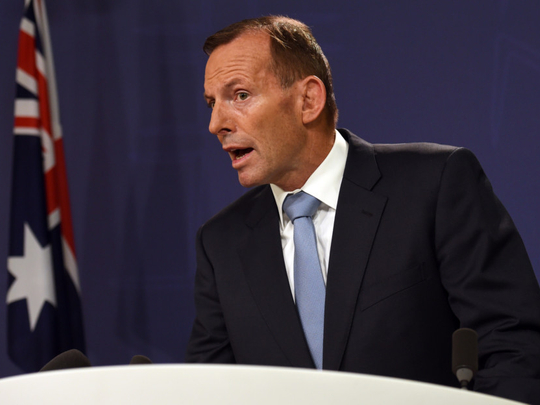

The Sun columnist Katie Hopkins’ call for gunships to send refugee “cockroaches” back to their own country, and United Kingdom Independence Party’s (Ukip) ploughing of the anti-immigration furrow are entirely predictable appeals to the chip-butty and pint version of Little England. What is most cringeworthy is that the Australian “solution” to boat arrivals is now regarded as best practice for the export market. Australians are repeatedly reminded, by both sides of politics, that a mixture of boat tow-backs and harsh detention centres on remote islands is the best-worst solution to destroy the business model of “evil” people-smugglers and prevent deaths at sea. Tony Abbott, the Australian Prime Minister, has been quick to recommend his approach to Europe after hundreds of migrants drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

“The only way you can stop the deaths is to stop the people-smuggling trade. The only way you can stop the deaths is in fact to stop the boats,” he said. “That’s why it is so urgent that the countries of Europe adopt very strong policies that will end the people-smuggling trade across the Mediterranean.”

While Hopkins was more concerned to appeal to the readership of “brilliant British truckers”, who get fined if they are caught with “feral humans” clinging to the chassis all the way from Calais, it is only a matter of time before Abbott’s advice is taken up and cruelty is presented as the only way to prevent further loss of life in the Mediterranean.

Since the election of the Abbott government, those people whose boats are not towed back to Indonesia are being held in detention camps, funded and managed by Australia, on tiny Pacific islands — the Republic of Nauru (formerly known more happily as Pleasant Island) and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea (PNG). Some are also on the remote Australian territory of Christmas Island. They have been advised that they will never be settled in Australia, even if they have refugee status. Instead, the government is seeking to resettle them in Camdodia, which has enough problems of its own, or in PNG. Others are being refouled back to Sri Lanka, Iran and even Vietnam.

The public disquiet is intensified by the repeated and inaccurate description of people seeking the protection of Australia under international law, as “illegals”. Much of this policy was set in place under the previous Labor government, which at one point sought to transfer the problem to Malaysia. The current government has taken it to an entirely new level of wretchedness in its determination to “stop the boats”. Speaking in Queensland earlier this month, Abbott boasted that “any other government, I suspect, would quickly succumb to the cries of the human rights lawyers”. “Our determination to save lives at sea is greater than [people smugglers’] determination to profit from putting people’s lives at risk.”

It is a distressingly hollow posture when saving lives at sea comes at the price of destroying them emotionally and physically on land. By now, you would think history would have taught us to see through such spurious moral justifications. Information to hand from the Australian Human Rights Commission and the Moss report, which examined allegations of physical and sexual abuse on Nauru and the failure of the authorities to exercise a duty of care, leave little doubt that human destruction is in full swing in the camps. It cannot be hidden by the pea and thimble game played by the Australian government, which claims the offshore detention camps are out of our jurisdiction and in the control of the Papua New Guinean and Nauruan governments.

The camps are entirely creatures of Australia, funded and managed under policies ordained by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The fate of asylum seekers returned to countries they fled does not seem to figure in Australia’s moral justification. Calls for a Royal Commission into immigration detention are growing louder, but are likely to fall on deaf government ears. Guardian Australia has reported the cases of asylum seekers who were tortured after being refouled, the prohibition of which under international law is steadfastly ignored by Australia.

And for that matter we do not know with any accuracy the numbers of people drowned at sea under the current policies, because they are “on water” operational matters subject to Kremlinesque secrecy.

The fate of asylum seekers returned to countries they fled does not seem to figure in Australia’s moral justification. Nor is there an adequate reckoning of lives lost in places of persecution because we have slammed shut the door on the escape route. The odd thing is that asylum seekers who can land at airports with papers intact are in an advantaged position. They are acceptable, because maybe there is some curious logic at play that they have not endangered themselves at sea.

European and British authorities can learn a lot about how not to handle the problem if they study the Australian “solution”. The only reason people get onto boats, with the high risk of drowning, is they have no hope. Human displacement is now such a massive problem that the boats will never really stop, no matter how hard we pretend to the contrary.

The Australian government policy is only tenuously glued together as long as Indonesia accepts tow-backs and as long as Nauru and PNG are bribed with enough money to roll over and handle Australia’s problem. If any of those ingredients collapse, then a more creative policy that gives people hope by a globally recognised resettlement response might have a chance. Australia’s current policy has been forged by a succession of drownings off the coast of Christmas Island, hand wringing by the major political parties, an expert panel headed by the former defence chief Angus Houston which, in 2012, recommended offshore processing in PNG and Nauru, cooperation with Malaysia and Indonesia and increase in the humanitarian intake.

The end game was a policy of “no advantage” — if you arrive by boat you should not be advantaged over people seeking resettlement by other means. Lives may well have been saved at sea, but at what cost if the cornerstone of the deterrent is based on transferring the human destruction from the sea to terra firma? The latest figures from the immigration department show that we are not really pulling our weight. In 2012-13, the Australian humanitarian programme was increased to 20,000 places from 13,750 places in 2011-12. A total of 20,019 visas were granted under the humanitarian programme, of which 12,515 were granted under the offshore component and 7,504 under the onshore component. It’ is a mere drop in the ocean.

We could comfortably treble that annual intake, with great advantages to the economy and nation-building — quite apart from the need to do something about restoring our humanity. It is not as though the government in Australia is without policy options. It could easily transfer its humanitarian intakes entirely to the near region, have agencies such as the UNHCR process the applications in camps in Indonesia and Malaysia paid for by the Australian government and shoulder a larger burden of the international crisis in human displacement. If refugees are given the hope of orderly resettlement, then there is no need for them to risk their lives on boats. Consequently, there is no need for policies that inflict another form of death by a thousand cruelties.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Richard Ackland publishes the law journals Justinian and Gazette of Law and Journalism.