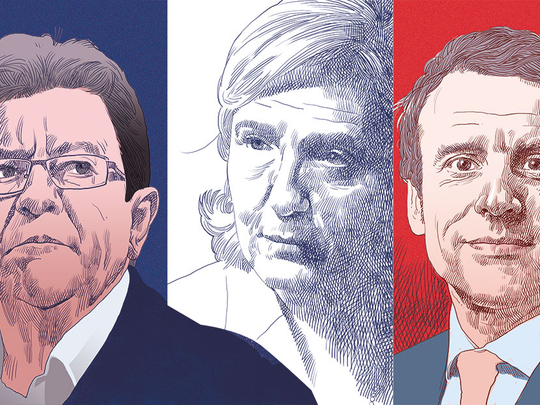

One man gives shivers to banks, businesspeople and the bourgeoisie. One man has been rising rapidly in polls, threatening the front-runners a week before the first round in France’s presidential election. One man has suddenly turned the French contest, locked for months between two favourites, into a four-man race.

That one man is Jean-Luc Melenchon, admirer of Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, sworn enemy of Nato and high finance, and candidate of his own ‘France Unsubjugated’ movement, who has been drawing tens of thousands to his rallies, especially the young, as he did here Sunday at Toulouse on the banks of the Garonne River. They came to hear a veteran French politician give them a dousing of old-fashioned Robin Hood-revolutionary rhetoric, with promises to tax the rich hard, give to the poor and start a “citizen revolution.”

The formula, delivered in fiery anti-capitalist phrases, and peppered with learnt philosophical abstractions, has put him within spitting distance of earning a spot in the election’s decisive second round on May 7.

‘Melenchon: The Insane Programme of the French Chavez,’ the right-leaning newspaper Figaro blared in a front-page headline last week. The candidate was delighted by this jittery jab.

“What is the liberty of the employee who is fired for not working on Sunday?” he asked the crowd, delivering repeated thrusts at capitalism. “What is the liberty of 120,000 families whose water is cut off because they can’t pay the bill?”

His advisers depict him as a kind of French Bernie Sanders. Unlike Sanders, though, he has no vigorous party establishment to block his way.

“Masters of the earth, you have good reason to be uneasy!” Melenchon yelled at the festive, youthful crowd Sunday, some wearing revolutionary Phrygian caps, as he stabbed the air with his fist and paced back and forth on the stage. “Give it up! Give it up!” the crowd yelled, a message clearly intended for Melenchon’s opponents.

“There must be decent salaries,” Melenchon shouted into the microphone. “That’s why the minimum wage will have to go up!”

Contest between two radical outliers

If this veteran of French politics — he started as a young Socialist senator in 1986 — pulls it off, France’s election could end up a contest between two radical outliers. Both Melenchon and Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Front gleefully promise a top-to-bottom shake-up, rejecting the country’s European Union membership, blasting its budgetary and deficit rules, and injecting France with huge doses of public spending.

The prospect of a Melenchon-Le Pen runoff, written off several weeks ago, no longer seems impossible. In a poll published in Le Monde on Friday, Melenchon had pulled to within 2 percentage points of both Le Pen and her nearest challenger, the centrist Emmanuel Macron, a former economy minister.

Melenchon’s advisers speak admiringly of Sanders. Their candidate’s score among 18- to 24-year-olds has shot to 44 per cent from 12 per cent in one month, according to Le Monde. Among 25- to 34-year-olds it has almost doubled, to 27 per cent.

Analysts say Melenchon has the momentum at a time when others, like the mainstream right candidate Francois Fillon, stagnate or fall in the polls. “He’s a total campaign warrior,” the political scientist Pascal Perrineau said.

Melenchon has come so far so fast that the other candidates spent part of the last week attacking him for the first time. Even the widely unpopular incumbent, President Francois Hollande, called him “simplistic.”

But as Hollande’s mainstream Socialist Party has collapsed, Melenchon, an ex-Trotskyist, has been the big beneficiary, making the Socialists look like pallid imitators of his own robust promises to cut back the workweek, lower the official retirement age to 60, raise taxes on the rich and hire many more civil servants.

What remains of the once-powerful French Communist Party backs him; Melenchon is not unhappy. “Mr Fillon reproaches me for being a Communist,” he said Sunday. “It’s a reproach I find totally tolerable,” he said, mockingly promising the right-wing Fillon a “handmade electoral jacket” in a reference to a recent scandal over his opponent’s expensive clothing habits.

Powerful resonance

In a country winded by 10 per cent unemployment, a plethora of unstable part-time job contracts for the young, a frozen job market and rising inequality, Melenchon’s message has powerful resonance. His supporters — the campaign said 70,000 turned out Sunday — speak of him with a fervour that surpasses that of all the other candidates, with the exception of Le Pen.

Yet the racially diverse crowd at Melenchon’s rally is nothing like the all-white, all-French one that comes to hear Le Pen.

“I work a lot and I’m badly paid,” said Inti Gomez, 40, who said he was a night receptionist in a Toulouse hotel, existing below the poverty line as he supports three on a salary of about $2,100 a month.

Although he works from 10pm to 7am every night, he had come out to hear Melenchon. “What’s really hard is this inequality that I’m forced to submit to,” Gomez said, bemoaning the fact that his education had gone for naught. “Change is possible,” he said. “I’m just taking advantage of this collective joy.”

Rene Amando, 60, said he had spent a lifetime working in chemical factories but retired early because his health had been damaged. “It’s his attitude of refusal,” Amando said, waiting for Melenchon to appear. “There is such a huge split between the big financiers and the people, who get poorer and poorer,” Amando added. “He gives us hope for a new kind of society, a more socialised and humane society.”

When Melenchon said the “presidential monarchy must be abolished,” he was tapping into an old French revolutionary tradition, one that sees revolution itself as an inherent good. The revolutionaries of 1789 France created a kind of civic religion around their revolution; Melenchon tries to do something similar. Even so, the crowd Sunday appeared a little bewildered by his abstruse references to heretics who had suffered for their beliefs, his advocacy of an obscure Latin-American alliance he is keen on and his admonition to “not let anybody exercise police power over thought.”

It roared though when he attacked President Donald Trump over the missile attack on Syria. “No Frenchman can accept a global gendarme who decided all by himself the good and the bad,” Melenchon said.

— New York Times News Service

Adam Nossiter has been a Paris correspondent for The New York Times since July 2015.