Learning to live with a cold peace

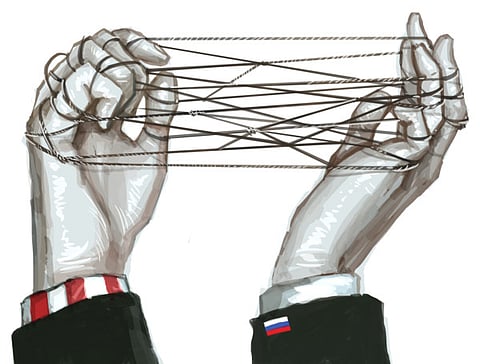

Russia’s annexation of Crimea may be a shock to the international system. But it need not be the beginning of a new Cold War

Senior US officials are deeply troubled by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, but self-interest may drive both sides to freeze this crisis before it gets too hot.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea may be a shock to the international system. But it need not be the beginning of a new Cold War — or even a watershed moment.

The officials I have spoken to in the US government are incensed by Russia’s disregard for international law and adamant that further violations of Ukrainian sovereignty will bring ever-increasing penalties from the West. Nonetheless, there is a sense among diplomats that an eye must be kept on the long view and there is hope that they can help contain the crisis and stabilise the situation.

“We’re focused on de-escalating,” one senior State Department official said to me in a conversation recently. “Getting onto this track where we can sit down and figure out where we’re going with Crimea, what’s going to happen. But we have to make sure that further provocations are not occurring, that people are pulling back, that no further moves take place in Donetsk or Kharkov or any of these places [in eastern Ukraine]. We’re going to do major things to try to prevent that from happening.”

One reason they will make that effort is because of the importance the Obama administration accords to initiatives like bringing peace to Syria and to halting Iran’s nuclear weapons development programme. At top levels within the State Department there is an understanding that Moscow has a central role to play in those talks with both regimes as well as a vested interest in keeping them on track, working alongside the US and the international community.

As to whether Russia’s interests in the Middle East may give the US and the West any leverage in trying to resolve the Ukraine crisis, the senior official with whom I was speaking said, “We’re going to find out. We don’t know the answer right now. It’s certainly one of the things driving them to consider what’s in the balance here. If we didn’t have those things going on, it would be a lot easier for them to say ‘screw this, we don’t have anything at stake.’ But because they are engaged in those other things, it may temper them a little bit.”

Constructive role

The issue, of course, is balancing toughness on Crimea and the desire to keep vital channels open. That’s part of the reason why the sanctions programme developed by the administration was designed so it could be escalated, as needed. “You don’t want to do so much in the first instance,” said the official (who is intimately familiar with the deliberations that led to the programme’s development) when we spoke last week. “You want it to be strong enough. And we’ve also sent a strong message that if Putin goes further, there are further big slugs of sanctions to come. So one day’s actions are not the measurement of our determination at all. And if he were to go into the east of Ukraine, then there’s going to be some real pain for some period of time.”

That, however, would lead to a breakdown in diplomacy elsewhere in the world that is clearly in neither side’s interests. “Obviously, that’s a risk you take,” the official said, “But you can’t be cowed by it.”

There is a strong sense that this is a message being delivered at the highest levels in the Kremlin, and that US Secretary of State John Kerry and US President Barack Obama have “no compunctions” in emphasising to the Russian leadership that further aggressive behaviour with regard to Ukraine will undercut their international legitimacy. At the same time, there is a feeling among top US policymakers that if Russia wants to restore its relationships with the international community after this crisis, one way it might be able to do this is actually by playing a more constructive role on issues like Syria and Iran.

“Besides, it’s also deeply in their interests to make those things happen,” said the State Department official, “because they have terrorist threats and they’re worried about those weapons falling into the terrorists’ hands and they’re worried about Iran going nuclear because they know what it can do to the region. So they have interests here and hopefully those interests combined with good diplomacy will bring them in. That’s the hope.”

In such conversations, one gets the unmistakable sense that the United States feels the Russians not only have a role to play both in Syria, in helping to find a way to ease Al Assad out of office, and in bringing the Iran talks to a successful conclusion, but that this role is very important to both of the processes. Diplomats are ready to proceed without them if need be, but they would prefer not to.

According to US calculations, perhaps as many as four or five countries are key to a successful outcome in Syria, including the Saudis, the Iranians, the United States and the Russians. Some may take the need for such coalitions as a sign of waning US clout, but it’s just realism. Progress on complicated international issues has always required the involvement of multiple actors — just as it always requires clear-eyed leadership about what’s possible and how to achieve it.

When asked about whether the Crimea issue might negatively impact the Syria and Iran talks at a town hall meeting for university students from around the US held at the State Department last Tuesday, Kerry said: “Well, obviously, we really hope not. We hope that Russia will realise beyond what is happening in Crimea that it has serious interests that haven’t changed. The interests that brought it to the table originally to work with us are the same interests today. And so if you’re serious about nonproliferation, then you shouldn’t walk away from the responsibility to make sure Iran does not have a nuclear weapon. If you’re serious about wanting to end a war in Syria and keep chemical weapons out of the hands of terrorists, then you shouldn’t walk away from your responsibility to help finish the deal that you helped to broker. What’s significant is we’ve been able, despite differences with Russia, to find areas of significant cooperation on the big-ticket items: Afghanistan, the START Treaty, nuclear weapons. On Iran, on Syria, on other things we’ve been able to cooperate, even as we have some differences and serious differences on other things.”

Another red line

“That’s the tragedy of what has happened with respect to Crimea,” he continued, “Nobody that I know of who reads the facts doubts Russia’s interests in Crimea. That’s not the issue here. Russia has an enormous historical connection to Ukraine. Kiev is the ... birthplace of the Russian religion. It has extraordinary connections. We know this. But that doesn’t legitimise just taking what you want because you want it or because you’re angry about the end of the Cold War or the end of the Soviet Union or whatever it is.”

There is also a sense within the top levels of the US diplomatic corps that recent speculation about whether this is the beginning of a new Cold War — as in Peter Baker’s article in the New York Times — is unconstructive. They would also like to move beyond what was seen as the unconstructive “zero-sum” arguments that helped trigger the Ukraine crisis in the first place — the message that Kiev must choose between East and West.

Even though this administration has had some bad experiences recently with declaring and then enforcing red lines, one gets the sense that with this crisis, there is yet another red line that has developed. If the Russians stop where they are right now, having annexed Ukraine, the US will decry it, exact penalties, and Russia will go through a period of turbulence and a degree of isolation on the international stage. But because there are shared long-term interests, ultimately, stabilisation and normalisation remain possible. However, even the cautious, canny diplomat with whom I was speaking, when asked whether that was still possible at this point, whether this might be seen not as the start of a new Cold War but perhaps simply as residue of the last one, said, “Thus far. As long as he doesn’t go in [to Eastern Ukraine]. If he goes in he has created a very different dynamic. Then we’re back to the very difficult place, very ugly. If he goes into the east ... if he goes any further than he’s gone now, it could signal a very ugly period. A very difficult period.”

For these reasons — based on conversations like this one and what I see as the calculated rationality behind what Putin has done (principles of international law and treaty obligations aside) — it’s my sense that it is more likely that this crisis soon stabilises and that in a matter of months the United States and Russia, pursuing their self-interests as ever, will be back to collaborating on the major issues that were the focus of most of their diplomacy in the months before the upheaval in Ukraine began. It is not just my optimism at work here. It is a still hopeful spirit I heard expressed at the highest levels of the US government even among those most scarred and angered by recent events.

While it is, of course, possible that Putin ups the ante with more aggressive action in eastern Ukraine —which would clearly be a game changer — if this crisis is contained and frozen roughly at the point it is now, it would not, in my view, constitute the beginning of a new era. Indeed, since the Balkan wars through the effective annexation of South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2008, from Russian support for Bashar Al Assad to its embrace of Edward Snowden, the relationship with Washington has been tense and turbulent for years. But pragmatism has also led the two sides to identify ways to work together. It is not so much that we should be focusing on the beginning of a new Cold War but rather that we must become better at handling the realities of an enduring and difficult Cold Peace.

— Washington Post

David Rothkopf is CEO and editor of the FP Group. His most recent book is Running the World: The Inside Story of the National Security Council and the Architects of American Power.