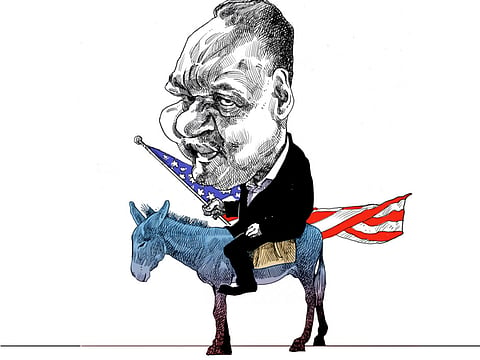

Jesse Jackson created modern Democrats

Can a white nominee, especially an ageing candidate, become the legitimate heir to Jackson’s politics of the empowered outsider, cutting across generational and other boundaries?

One of the more arresting moments in the American presidential campaign came last week, when Hillary Clinton had a spirited exchange with activists from Black Lives Matter. “Look, I don’t believe you change hearts,” Hillary said, when pressed about her support for their goals. “I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate.”

In that instant, Hillary did not sound like a “Clinton Democrat” — at least not the kind her husband implied he was in the early 1990s when he emphasised the theme of “responsibility”, and sternly told a black audience: “I cannot do for you what you will not do for yourself.” Bill’s words seemed more evocative of those used in 1984 by one of his adversaries, Jesse Jackson, who reminded voters how structural changes had come only through activism that had “ended American apartheid laws”, “secured voting rights” and “obtained open housing”.

Jackson, who is now 73, has quietly become part of the political landscape again. Early last week, Hillary’s chief rival at the moment, Senator Bernie Sanders, who has been drawing the largest audiences in the Democratic presidential field, made a pilgrimage to Jackson’s office. Sanders has been reminding reporters that he stumped for Jackson during both his presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988 — the second time helping him win the Vermont primary.

This interest in Jackson may seem anomalous, but in fact is long overdue. More than anyone else, he is the visionary of the current Democratic Party in its transition out of the 20th century and into the 21st.

Conventional wisdom says otherwise. Its account of the party’s rebound from the defeats of the 1980s treats Jackson sceptically and gives the saviour role to Bill. It is true that Bill’s appeal to working-class and middle-class voters — those “who work hard and play by the rules” — were effective in their time. The electorate was still overwhelmingly white (nearly 90 per cent, compared with about 70 per cent today) and the Democrats were desperate to lure back those people who had defected from the party amid the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s and voted for Republicans, beginning with Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Today, the 1990s strategy sounds archaic, while Jackson’s earlier appeal seems more closely in sync with where the party is now. Take, for instance, his speech at the 1984 Democratic National Convention, when he said of his Rainbow Coalition: “The Rainbow includes lesbians and gays. No American citizen ought be denied equal protection from the law.”

The “from” is apt in the context of the issues that preoccupy today’s progressives — police killings of young blacks; punitive laws that bar immigrants, even those who came to the United States as children, from attaining full citizenship; state and local ordinances that allow employers and landlords to discriminate against gay and transgender citizens; voter-registration restrictions in many states that seem aimed at minority populations.

Protection “from” such laws resonates in particular with millennials, who now form the nation’s largest population cohort (more than 80 million), 43 per cent of whom are nonwhite and 7 per cent of whom say they are gay, bisexual or transgender. These are the constituents the eventual Democratic nominee will need to attract in 2016.

Yet, Jackson’s two campaigns are rarely invoked today. Why? One reason is that he lost. The second is that he has often been blamed for pushing the Democratic Party to the left.

In this telling, rescue came from the centrists at the Democratic Leadership Council. But to Democrats in 2015, some of the brilliant strokes in the 1992 campaign of the DLC’s star, Bill, seem distinctly un-liberal — like his return to Arkansas to preside over the execution of a death-row inmate and the speech he gave to the Rainbow Coalition in which he sharply rebuked another participant, the rap performer Sister Souljah. As president, Bill signed the Defence of Marriage Act in 1996 (and has since apologised for doing so).

Today, those actions seem those of a Republican, not a Democrat. The Jackson outlook prevails. The change can be measured in the current attitudes of Stanley Greenberg, the Clinton adviser and pollster who made his name in 1985 when he surveyed disillusioned white voters in Macomb County, on Detroit’s outskirts, and argued that appealing to them was the Democrats’ way back to a majority. The “defector” Democrats he interviewed now believed the party was “preoccupied with the needs of minorities” — including gays and feminists — and “no longer responded with genuine feeling to the vulnerabilities of the average middle-class person”.

But in 2008, Greenberg renounced that old strategy. “I’m finished with the Reagan Democrats of Macomb County,” he wrote in the New York Times after Barack Obama’s first victory.

Greenberg urged analysts to study another Detroit suburb, Oakland County, “home to the affluent, business-oriented suburbanites of Birmingham and Bloomfield Hills, some of the richest townships in America”. While “just a quarter of Macomb County residents have college degrees,” he wrote, “more than 40 per cent do in Oakland”. What is more, “almost a quarter of Oakland’s residents are members of various racial minorities”.

This electorate helped make Obama the first Democrat elected president with more than 50 per cent of the popular vote since 1976, when Jimmy Carter squeaked by with 50.08 per cent. In 2012, when Obama received more than 50 per cent of the vote for a second time, he joined a select group that includes only three other presidents (Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan) in the last 100 years.

In a sense, Jackson’s role in laying the groundwork for a future majority might be likened to that of another so-called radical who was soundly defeated in his presidential campaign: Barry Goldwater.

Like Goldwater, Jackson rejected what was then called “me too” politics — that is, mimicking the other party — and instead ran as a proudly ideological candidate who made direct populist appeals to the party’s base. And Jackson swept in new voters, as Goldwater did for Republicans. Just as Goldwater’s brand of free-market economics and cultural conservatism led to the election of Reagan, so Jackson’s vision of culturally diverse liberalism opened the way for Obama.

Obama indirectly acknowledged Jackson’s legacy in his victory speech in November 2008. Jackson was in the audience at Grant Park in Chicago that night as Obama promised to lead the “young and old, rich and poor, Democrat and Republican”, and the “black, white, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, gay, straight, disabled and not disabled” — echoing Jackson’s words in 1984, when he itemised a diverse coalition that included “the white, the Hispanic, the black, the Arab, the Jew, the woman, the Native American”, along with Asian Americans and “the young, the old, the lesbian, the gay and the disabled”.

Can a white nominee, especially an ageing candidate such as Hillary or Sanders (or Joe Biden if he should decide to run), become the legitimate heir to Jackson’s politics of the empowered outsider, cutting across generational and other boundaries? It will be many months before we know the answer. But taking a fresh look at the legacy of Jackson, true architect of the modern Democratic Party, is one place to begin.

— Washington Post

Sam Tanenhaus, the author of The Death of Conservatism and Whittaker Chambers, is working on a biography of William F. Buckley Jr.