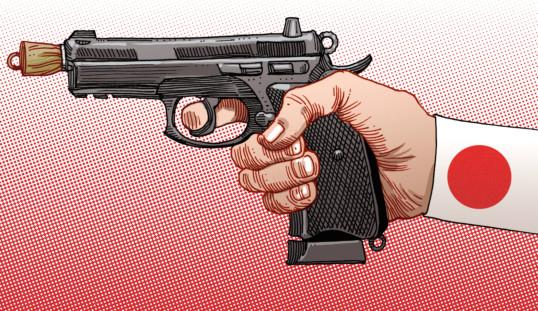

Japan’s Diet has begun the process of passing legislation that would authorise the country’s self-defence forces to fight in foreign conflicts, in apparent violation of the country’s pacifist constitution. And that’s a good thing, despite the apparent danger it poses to the rule of law. Behold the power — and the danger — of a living constitution.

The provision in question is Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, which says “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation” and promises that “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained.”

No other country has such a remarkable pacifist guarantee in its constitution. It was imposed by the US occupation after the Second World War. Even if a whole people wanted to be at peace with the world, there would ordinarily be no good reason to renounce the right to fight. But General Douglas MacArthur wanted a definitive and clear message sent to the Japanese that their imperial ambitions were being permanently shut down. Forcing them to renounce war as a legitimate tool of foreign policy was akin to forcing the emperor of Japan to renounce his divine character.

Remarkably, Japan’s constitution has been a resounding success, notwithstanding the fact that it was written by Americans in English, translated hastily to Japanese (with some errors), and promulgated under conditions of occupation.

In this sense, the Japanese constitution poses a fascinating puzzle for constitutional theorists who think such a document can only be legitimate and effective if it reflects the will of the people. At the time it was adopted, the Japanese charter very clearly did not reflect the will of the nation — only its acknowledgement of its defeat. Yet over time, it’s achieved the respect we associate with popularly adopted constitutions.

Now, under the prime-ministership of conservative nationalist Shinzo Abe, a majority of the legislature’s lower house is acting in apparent violation of the venerated constitution — and there’s reason to think the legislation will pass. Abe has spoken of Japanese hostages captured and killed by Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), but that’s just window dressing. Everyone understands that the real reason for Japan to develop offensive military capabilities is the rise of China.

Since the Second World War, Japan has relied on the United States to defend it from the much larger China. What’s changed is that China’s military is getting bigger, its regional posture is increasingly aggressive, and the US seems increasingly uncertain about its commitment and capacity to defend its Asian allies if push comes to shove. Geopolitically, increasing military capacity makes all the sense in the world for Japan. Any country in its situation, with its economic capacity, would be taking steps to grow its military.

The catch is Article 9 of the constitution. It would seem to leave no room for such increased military capacity.

What’s to be done when a constitutional provision conflicts with a country’s pressing self-interest? Two plausible options present themselves. One, preferred by legal logic, is to amend the constitution to fit the new circumstances. The trouble is that once a constitutional provision has achieved the respect that comes with time, it can become very hard to change. And because a constitution can come to be seen as a coherent whole, changing one provision can lead to unsettled expectations about whether other provisions might be changed. Finally there’s the problem of whether a supermajority can actually be persuaded to take national interest into account.

To strict constructionists everywhere, these difficulties in amending a constitution are part of the whole point of the document. Written constitutions tend toward conservatism of the small-c, Burkean variety. Because they’re hard to change, they promote the status quo.

But as US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson once put it, the Constitution is not a suicide pact. Jackson was an inveterate pragmatist who knew something about geopolitics after serving as chief prosecutor at Nuremberg. His point was that a constitution must be interpreted pragmatically, to serve the nation’s interests and help it avoid existential threats. It applies equally to Japan as to the US.

That leaves the second option: interpreting the constitutional provision flexibly so as to accommodate the change that the nation acknowledges to be necessary. In the case of Article 9, the argument should be that Japan’s existing self- defence forces already count as “land, sea, and air forces.” Thus, the literal meaning of the provision has already been abandoned in favour of its spirit.

And that spirit remains the spirit of self-defence. After all, Japan isn’t planning to invade China or anybody else. It just needs expanded military capacity to recognise the growing threat of China. In military affairs, sometimes the best defence is a good offence.

If Article 9 can’t be amended, then Japan’s legal authorities can — and should — move in the direction of interpreting it to allow expanded military forces in the spirit of self-defence. There’s nothing magical about using troops abroad — it can be defensive as well as offensive. In this way, the spirit of Article 9 can be preserved, even as its letter is limited.

This approach of the living constitution bears risks. Thus flexibly interpreted, a constitution can be interpreted out of existence. The only protection lies with the nation’s legal-constitutional actors, whose influence inevitably grows under a living constitution.

But the risk is worth the benefits. In the end, there’s only one alternative to a living constitution — and that’s a dead one.

— Washington Post