Bernie Sanders may be an astonishing phenomenon, but what is even more astonishing is how America, including in particular its young, its liberals, its independents, and its progressives, has embraced a figure who was unknown outside the state of Vermont a mere eight months ago — a figure who, nevertheless, virtually tied with the mighty Hillary Clinton at the Iowa caucuses last Monday — Hillary’s win by a pathetic 0.2 percentage point-margin is no win and who may very well beat her in the New Hampshire primaries early this week.

Were Bernie — as his supporters are wont to call him — to win his party’s nomination, and in November the general election, he would be the first socialist, the first Jew and the first septuagenarian to occupy the White House (Ronald Reagan was 69 when he was inaugurated in January 1981).

Sanders, President of the United States? That’s a long, very long, shot, you say. Yet, that’s also what we all said about his seemingly slim chance of going anywhere when he launched his campaign in late April last year. Indeed, a leading online gambling site at the time put the odds of the man staying the course at 50 to 1. Needless to say, few people bet the family jewellery on what then seemed like the quixotic venture of an obscure senator from an obscure state in New England with Buckley’s chance of beating or even nipping at the heels of the invincible Hillary Clinton.

A socialist president who pledged, among other provocative promises, to cut Wall Street down to size and teach those greedy banks a lesson? Come, come now, the man was meant as a sideshow.

Yet, the hour met the man, for he appeared to tap into a long dormant undercurrent in the psyche of a large segment of everyday America, a segment that sought something innovative, daring, different, perhaps even revolutionary, in American political culture. And in Bernie Sanders these folks found a leader whose brow, like theirs, was middle, but whose message was suave.

A few days after his announcement to run as his party’s nominee for president, on May 26 last year, Sanders was in Minneapolis on his way to address his first rally outside his New England turf. The car he was being driven in appeared stuck in traffic. According to a news report in the Washington Post, the senator, anxious not to arrive late to the event, asked the field director accompanying him: “Is there a wreck ahead?”

No, came the response, they’re here to see you — all 3,000 of them, many standing outside because the hall was full. And the crowds kept growing as he kept on campaigning, even in red-state strongholds like Texas, putatively enemy territory.

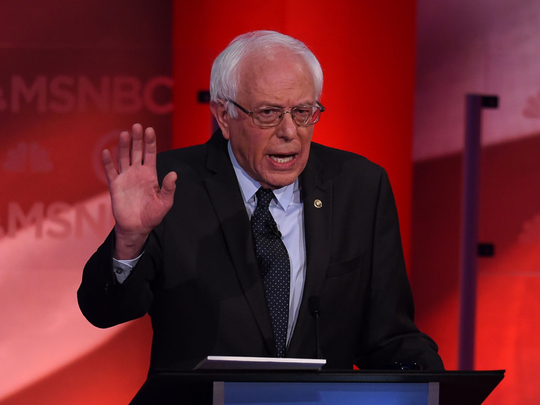

Let’s face it, there was always something engaging about this dishevelled septuagenarian (Sanders will turn 75 six weeks before the general election), with his mop of unkempt Albert Einstein hair, as he railed, at rallies across America, against “tax breaks for the wealthy”, an improbable presidential aspirant who went from single digits in the polls six months ago to a virtual tie with Hillary in Iowa last Monday, an unknown who started from nothing, with nothing, to a serious Democratic contender for president of the United States. And the money poured in, most of it — since he spurned “big money” — from supporters whose contributions averaged $40 (Dh147).

How do we explain this phenomenon? Modesty aside, we explain it easily. Here’s a new kid on the block, and he is possessed of, possessed by, a message about how the inequalities in social life, the brazenness of the one-percenters, the excesses of Wall street, the arrogance of the “establishment (a dismissive term evocative of the radical chic lingo of the 1960s) and the costly foreign entanglements approved by Washington, are secreting a poison in the blood of the American body politic.

The analogy he was evoking of America was of a man who had missed a step in a dark staircase, and now it is time for Americans to engage in the idiom of the highest ideals. With that, he was saying, new possibilities open up in society and Americans’ collective imagination expands. It is a message, both candid and direct, that appears to have found an audience, even if, on one level, subliminally.

But that’s not all. Some Bernie supporters may have turned to Bernie because they had opted to turn away from Hillary. The first woman aspiring to be president has run a campaign that emphasised her accomplishments over the last two decades. The end result was not just a me-me message, but a message that threw a furtive glance over her shoulder to the past. The first socialist aspiring to be president, on the other hand, has run a campaign that eschewed the me-me factor — Bernie, for example, never gloated over or ever reminded his audiences, not once, of his days as a young idealist and activist in the 1960s who was out there in August 1963, joining The March on Washington, when Martin Luther King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech — but rather focused on the future.

And Americans prefer, instinctively, to focus on the potentiality of their future rather than to dwell on the actuality of their past. It’s in their national character, their cultural DNA. To that extent, Bernie, from the outset, had it right. Hillary did not.

After watching the first Democratic debate in October last year, I wrote a column in which I effectively dismissed Bernie Sanders as a grumpy old man. I was wrong and, yes, I got ‘Berned’ in the process.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.