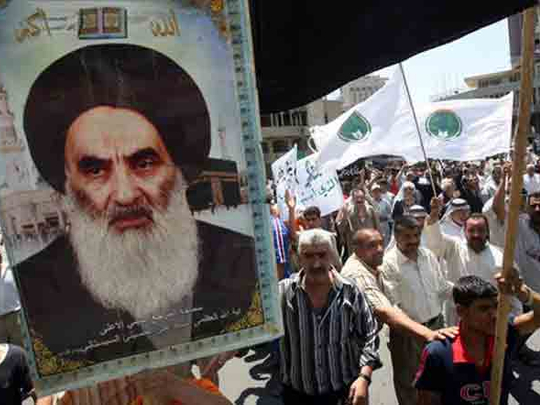

Is the Grand Ayatollah Ali Al Sistani Iraq's Grigori Rasputin? Needless to say, there are so many differences between the two men that it seems illogical to compare them. However, it seems that the utmost faith of the Russian Tsaritsa Alexandra Feodorovna, wife of Tsar Nicholas II, in the healing powers of the man who was called, among other names, the mad monk, is matched today by the belief of Iraqi politicians in Al Sistani. The major difference is that Al Sistani did not place himself on such a high pedestal.

All Iraqi politicians, be they Sunnis, Shiites or Kurds, head for the cleric's humble house in Najaf whenever a problem arises or they want to prove a point or make a political decision.

All of them drop his name in their statements to enhance their position, and most of them give the impression that they have gained his blessing for their endeavours.

After the State of the Law coalition headed by Nouri Al Maliki and the National Iraqi Alliance decided to unite in a front that will presumably give them the power to establish a government, both entities agreed that they would defer to Al Sistani should any dispute arise between them.

Following this announcement, however, a source close to Al Sistani told news agencies that the cleric was not aware of the agreement, and had not been consulted.

The questions that should be asked are: Who is Al Sistani, how did he become so powerful in a country where virtually every street needs a military force to keep the peace, and each and every governorate may call for independence at any given moment?

Al Sistani was born in Mashhad, Iran, to a family of religious scholars. In 1951 he went to Iraq to study in Najaf under the late Grand Ayatollah Abu Al Qasim Mousavi Khoei. Al Sistani rose in religious rank to be named a marja in 1960. At the unusually young age of 31, Ayatollah Al Sistani reached the senior level of accomplishment known as ijtihad, which entitled him to pass his own judgments on religious questions.

What makes Al Sistani so special to Iraq in these very difficult post-Saddam days?

Sistani opposes the partitioning of Iraq, and in particular the ceding of Kirkuk to the Kurds. In fact, were it not for Al Sistani, the Iraq map would today look very different. The cleric also opposes sectarian strife, and stood with the Sunnis after the bombing of the Imam Al Askari shrine in Samara, protecting them from possible revenge attacks. He urged Iraqis not to resist the invading forces because that would only prolong their stay. He has pointedly refused to meet with US government representatives. It was his opinion that prompted the US to allow the UN a greater role in Iraq's reconstruction, as well as to allow a constitution to be written prior to elections, which he urged be held in 2004. He insists that Iraq is a part of the larger Arab world, and — somewhat surprisingly — opposes Iran's attempt to dominate the country. Most importantly, he is against the notion of velayat-e-faqih, or rule by Islamic jurists.

Moreover, Al Sistani has opposed efforts to move the Shiite theological school, or Al Hawza, to Qom, Iran, and insisted that it remain in Najaf despite the unstable state of affairs in Iraq.

Al Sistani has emerged as a wise cleric who has opposed moves that could might have made Iraq's future even more unpredictable. However, Iraq's current politicians are not as wise as he is.

Wrong path

Whenever there is an obstacle or a hurdle that has to be overcome, the Iraqi politicians start their trek to Najaf. The danger is that these politicians are falling into Iran's trap, seeking — despite Al Sistani disavowal of velayat-e-faqih — the creation of a state in which political Islam rules.

Given Iraq's multitude of sects, religions and ethnic groups, applying velayat-e-faqih is like embracing a Molotov cocktail that is likely to explode into a civil war.

Time and again, Al Sistani has emphasised that he distances himself equally from all Iraqi political blocs, parties, groups and individuals.

He also understands the importance of Iraq's constitution, for without it, what is the use of Iraq's newfound democracy?

In the words of Steven Lee Myers of The New York Times, no one man in Iraq had more power to change the outcome of the country's elections than Al Sistani. And yet he has refused to wield it, shaping the relationship between Islam and the state at a crucial juncture in Iraq's history.

Al Sistani wants to guide but never rule, a distinction that is not understood by Iraqi politicians who go to see him to prove their points of view, and return claiming to have received advice from the old, ailing man who wants nothing more than a strong, united Iraq.

Iraq has reached a very delicate and dangerous crossroads, for without a government, life is at a standstill. Without a civil government that does not resort to sectarianism and quotas, Iraq will remain weak, fragile and likely to be controlled by its neighbours' agendas and schemes.

It would be wonderful if Iraq's politicians were more like Al Sistani.