Iran’s deal is not just with US

Republican opposition to the nuclear pact does not take into account America’s global partners’ resolve to make it work

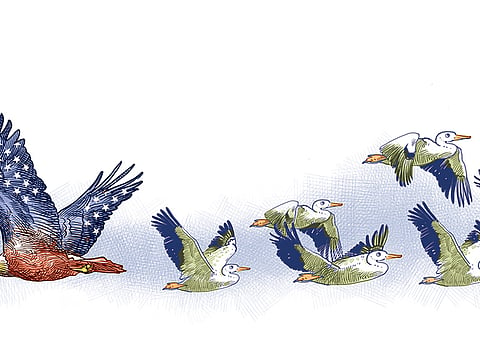

The increasingly vicious American opponents of the international accord over Iran’s nuclear programme are treating the fight to approve the deal as part of America’s domestic Republican-Democrat standoff and have overlooked that fact that the deal was between Iran and the entire international community. It was signed by China, Russia, Britain, France and Germany as well as the United States and Iran, and was backed by the European Union as an active partner in the talks.

The agreement to end sanctions in return for more Iranian transparency and many other steps was not a unilateral deal between the US and Iran, which means that even if the US Congress disagrees with the American president and fails to approve the deal, such a decision would only be a local American issue.

It might be that the Obama administration will find enough votes in Congress to approve the agreement. The Republicans have introduced a bill rejecting the agreement that may well pass in Congress, but the Democrats hope to stop it in the Senate. And even if this rejectionist measure passes both Houses, the president has the authority to veto the bill as long as the Senate cannot muster a two-thirds majority to overturn his presidential veto.

But such a process is definitely not the ringing endorsement of a major breakthrough that Obama would love and the level of political chaos in Washington is forcing the wider world to review its options in case Congress stops America’s participation. The international deal will remain valid for all other signatories and it will be taken to the UN Security Council where approval will allow the phased withdrawal of UN sanctions.

Iran can also approve the deal internally despite its hardliners’ public resentment of the terms and the Iranian government will therefore be obliged to stick to its terms, which it may want to do as such rectitude will position the Iranians as a responsible international partner in stark contrast to an America that has rejected its own deal.

Diplomatic process

But even if the US backs off, the Europeans, Russians and Chinese will start to abandon the sanctions that they have been complying with on the condition that there is a diplomatic process. The Russians have already gone ahead with a halted missile deal and from all over the world, company heads from many sectors are rushing to talk to the Iranians ahead of the expected deal coming into effect and the withdrawal of sanctions. More than 30 years of halted investments have created a huge opportunity for investment, particularly if the companies can also offer attractive financing options, which would let the Iranians off the hook of paying cash right now.

In addition, many Europeans have been clear that they see the use of sanctions as a diplomatic tool and not as a long-term instrument of punishment. So without any talks, or hope of any talks, they would see little point in the sanctions.

Across the European capitals, there is no debate about the deal and it is accepted that it is going to happen. There is no equivalent of the Israeli lobby in Washington, forcing parliamentarians and ministers to disagree with their president and the various European Jewish groups have a profound dislike for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s extreme opposition to the deal, with his apocalyptic talk of an existential threat to Israel.

There will be serious political fallout on several fronts from a US rejection of the Iran deal. First, US President Barack Obama’s administration’s credibility will be wrecked as no one will trust him to deliver on any international undertaking as it could be stopped dead in Congress by recalcitrant Republicans preparing for next year’s presidential elections. A rejection will certainly call into question the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which is a centrepiece of Obama’s pivot to Asia and a major part of his strategy to peacefully contain Chinese expansionism.

Second, it will greatly strengthen Iran’s isolationist conservatives that Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has struggled to squeeze out of influence after taking over from his predecessor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. They will delight in the failure of the more internationally-minded Rouhani and will work to minimise the authority of Rouhani’s presidency, while also appreciating the greater revenues pouring into the country after sanctions finish.

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has always been lukewarm about the deal and has only backed it after Rouhani persuaded him that Iran’s economy desperately needs it. Khamenei will seize on a rejection by Congress and announce that he never trusted the Americans. This hardline victory will demolish the hopes of the huge numbers of young and educated Iranians who want a new chance at reform and whom Khamenei rightly fears.

Thirdly, these conditions can well mean that Iran will abandon the deal itself and the hardliners in charge will feel free to renew Tehran’s previous nuclear programme so that within a very short time, the Iranians can have tens of thousands of centrifuges enriching tonnes of uranium, giving them enough to make multiple bombs within days. Stopping this threat is one of the core arguments from the supporters of the deal.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox