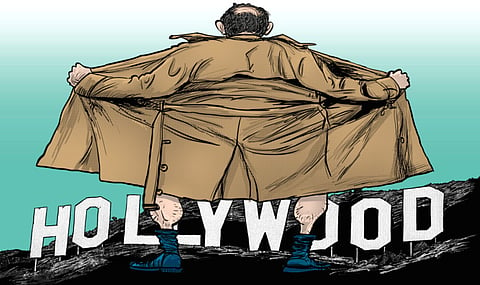

How Hollywood can devise a system to save future victims of abuse

Women and men know that coming forward will hurt them. This stalemate means that part of the solution has to come from outside

‘These are dark days for Hollywood rapists,” a friend of mine joked on the phone recently.

I was grateful for the laugh. Since the weekend, the open wound created by Harvey Weinstein has prompted actors, writers and crew members to recall their own hellish tales of assault. For those of us who work in TV and movies, the stories pile up in our social media feeds and phone texts. They all have two things in common: One human disregarded another human’s agency; and the names of the offenders are not revealed.

In the old TV show, Dragnet, names were changed to protect the innocent. Now they’re dropped to protect the guilty. Victims are offering details of inappropriate behaviour while leaving out the one detail that could make the biggest difference. Still, who can blame them? Not me. It’s been almost 30 years since I joined this not-very-exclusive club, and I’m not naming names. My fear is not of the person, but what speaking up will signal to the community.

“Hollywood is the only place where if someone screws you over and you call them on it, you’re the jerk,” a writer friend once told me. We were talking about another friend whose idea for a TV show had been stolen by a big-name producer. The injured writer made a calculation and decided it’s not worth angering a gatekeeper when he can shut the door in your face. Then who have you hurt? (Hint: Not the gatekeeper.)

That writer felt he had no recourse. It’s the same with victims of sexual assault. Hollywood is built on relationships and the way you keep relationships is by playing nice. If I bust my assaulter, somehow that makes me the troublemaker. Suddenly, I’m the jerk.

“I moved here 30 years ago this month,” actress Julie Warner wrote on Facebook. “There exists a pernicious disease of sexism here in Hollywood ... I could tell my truths about the powerful men who crossed the line with me in my 20s, and 30s, attempted rapes, harassment, vile truths, but I don’t want to freak my kid out. I could also name the powerful men and women who knew and told me to cope, but never to reveal if I wanted to keep working.” Julie hashtagged her compelling and moving post: #Nopitypleasejustchange.

Julie’s post took me back to 1991 when I watched Anita Hill testify at Clarence Thomas’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings. I was riveted by Hill’s honesty, bravery and poise. At one point, senator Dennis DeConcini (Democrat, from Arizona) said he couldn’t understand why she hadn’t quit her job if her boss made the workplace so uncomfortable. “Well, I think it is very difficult to understand, senator,” Hill answered. She explained that she stayed “because I wanted to do the work ... and I did not want to let that kind of behaviour control my choices”.

The desire to keep doing what we love supersedes the desire to penalise bad behaviour.

It’s not just powerful male executives who abuse their position. A successful male writer reached out to tell me about a predatory female executive who regularly feasted on the talent, pressuring one married writer to have sex with her in the office. In his 20s, my friend had been cornered by a different high-powered executive and succumbed to the pressure. “Her first words after we finished were, ‘By the way, there’s a project, I want to pitch you later’,” he texted. It felt transactional, but my friend said he’d gone along because he thought it would’ve hurt his career to say no. “Do you believe me?” he asked.

That broke my heart. “Of course, I do,” I wrote back.

Not naming names allows the predators to persist, but naming names hurts the victims. This stalemate means that part of the solution has to come from outside. The enablers are a huge part of the problem. At the very least, people need to start believing the victims and stop defending the perpetrators. At one of my more recent jobs, a crew member was fired after three women reported that he had rubbed up against them inappropriately on the set. My male boss came into my office to discuss the situation. He shook his head. “It’s just a shame,” he said.

“Those poor women,” I replied.

He looked, startled. “No, the guy. It wasn’t like he was grabbing ...,” he said. Then my boss added the kicker: “I really feel for him. He has kids.”

Talent agencies and entertainment lawyers can do more to protect their clients. Agents could start circulating a list internally: “Here are the people who have been reported for treating clients of ours unprofessionally.” If an agency’s own client lands on that list, the agents should question their complicity in potentially criminal and certainly damaging behaviour. And if an agent or manager advises a client who has been mistreated not to say anything, that advice should be followed by, “I’ll say something and make sure you’re protected.”

Also, if an actress or actor tells their lawyer that they’ve been emotionally abused or physically assaulted, that lawyer should feel an obligation to contact the abuser’s lawyer and put them on notice. The Guilds-Writers, Directors, Producers and Screen Actors-could gather and spread more information. Journalists can make a difference, too. Some names of offenders crop up repeatedly, and reporters should follow those leads. If those reporters get the silent treatment from the network, studio and managers, that complicity should become part of the story.

Julie Warner had a lovely idea: Women-and men-in the industry should meet in private and confidential settings to share their experiences. If some victims still didn’t feel comfortable speaking candidly, they could scribble down names and throw them anonymously into a hat. When a name comes up more than once, the group could be alerted and given the chance to come forward together. Perhaps just knowing that we’re all comparing notes would change the worst behaviour.

The ultimate goal is that the assaulters are not just tried in a court of public opinion, but in an actual court of law. So far, the predators seem to be a step ahead of prosecution. Bill Cosby has avoided jail. Roger Ailes ran out the clock. Weinstein supposedly flew off in a private jet to a sex rehab clinic in Europe.

Hollywood culture could use some sex rehab, too. It would be so nice to live in a place where if someone screws you over and you call them on it, they’re the jerk.

— Washington Post

Nell Scovell is a Hollywood writer, director and producer who co-wrote Lean In with Sheryl Sandberg.