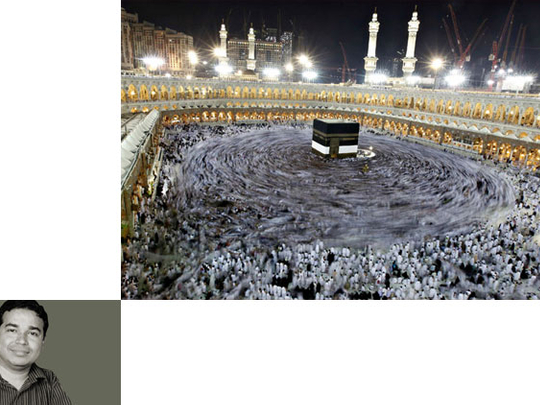

The sea of humanity perpetually surging, swirling and revolving around the majestic, black and cubical structure. The sight of men and women in white going around the black-robed Kaaba during the annual Haj and at other times throughout the year never ceases to awe, inspire and fascinate you. You do not have to be a believer or even get close to the Kaaba to be part of the soul-stirring experience. No one remains unmoved by the sight of the faithful from all parts and corners of the world — black and white, tall and short, rich and poor — submit themselves before God as equals in the brotherhood of faith and humanity.

As Keith Ellison, the first Muslim member of the US Congress put it after his Haj a couple of years back, you forget who you are — black or white, American or African — and where you come from when you are before God, circling the Kaaba in a two-piece unstitched garment. Indeed, nothing else celebrates the oneness and unity of humanity and universal brotherhood as the Haj does when more than three million pilgrims from around the world undertake the journey of a lifetime to Makkah.

Interestingly, the world’s greatest pilgrimage and congregation does not commemorate something the Prophet of Islam (PBUH) did or ordained. By undertaking this passage to Makkah, mandatory for everyone who can afford it, Muslims retrace the historic journey of Prophet Abraham and his immortal sacrifice near the Kaaba thousands of years ago.

Abraham is also respected by the Jews and Christians. All Jewish prophets and Jesus Christ are related to the Patriarch who originally came from Iraq. He is also revered by Muslims as the architect of the Kaaba along with his son Ishmael (Esmail to Muslims) and ancestor of the Last Prophet (PBUH).

By retracing, reliving and celebrating Abraham’s journey, pilgrims experience his unquestioning faith, total submission and willingness to sacrifice what was most precious to him, his only and beloved son when ordained by God in a dream. How Esmail was rescued at that last minute is a separate and equally fascinating story.

What really fascinates me is how the three great monotheistic faiths — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — are inextricably linked to each other and are united in Patriarch Abraham, the progenitor and grandfather of prophets whose followers are spread across the globe and form the majority of human race. Notwithstanding the long history of crusades and conflicts spanning several centuries between them, the three religions have much more in common than their followers care to recognise.

Listening to the historic Haj sermon from Masjid Nimra in Mina by Grand Mufti Shaikh Abdul Aziz Al Shaikh, one is struck by the number of references to the prophets and scriptures that are sacred to both Christians and Jews as well as Muslims. Why is the world then ignorant or unaware of this aspect of Islam — this all-embracing quality of the much-maligned faith? In fact, today not even many Muslims are familiar with this generous spirit of tolerance and acceptance that suffuses their faith. Or at least once did.

The predominant theme of the Haj sermons, delivered before millions of pilgrims and watched by a global audience, over the past few years, has been a constant emphasis on peace, tolerance, patience, reason and progress.

This year too, calling the believers to follow Islam in its true spirit, the Grand Mufti repeatedly asserted that there is no place for aggression and violence in the faith. “Islam teaches patience and tolerance and abhors all types of violence in the society,” he added, asking the believers to respect all communities and creeds and follow Islamic teachings to promote peace and universal brotherhood. Repeatedly warning against suicide and violence in the name of faith, Al Shaikh asserted that there is no association between Islam and terrorism.

Of course, we have heard all this before — repeatedly — in the sermons by the Grand Mufti, Imam of the Grand Mosque and other leading figures in the Islamic world. But does the message get through to the believers and the larger world? If the answer is yes, why is there little or no change in the world’s perception about the followers of Islam? How do we deal with the problem?

While watching the Haj proceedings on television between my usual channel surfing, I stumbled across The Message, Moustapha Akkad’s timeless magnum opus and a chronicle of the early history of Islam. Akkad, once known for his Halloween movies, also gave us the epic, Omar Mukhtar: The Lion of Desert, played to perfection by the inimitable Anthony Quinn. The gifted Arab American filmmaker managed to recreate some of the magic of Islam’s early phase in The Message despite the ideological and religious red lines and limitations that constantly challenged him.

While nothing can perhaps ever do justice to recounting the ordeal of early believers, The Message comes closest to offering a rare insight into how Islam won over the Arabs to spread far and wide within two decades of its dawn. The force of the Prophet’s (PBUH) extraordinary personality epitomising the universal message he brought swept Arabia and beyond in his own lifetime.

After the Prophet’s (PBUH) death, it was not the cutting edge of Islam’s sword as many suggest, but the revolutionary nature of its message and its liberating teachings that conquered the hearts and minds everywhere; the message championing the unity of God and humanity and preaching simple but universal values like honesty, equality, justice and above all — oneness of humanity and God.

It was this revolutionary message that opened doors for the early Muslims wherever they went — from Persia to Spain and from India to Indonesia. Contrary to what its detractors suggest, Islam did not spread to the far corners of Asia, Africa and Europe riding on the military conquests of the Arabs, Turks and Mughals but thanks to the endearing simplicity, honesty and truthfulness of spice traders who were enthusiastically welcomed on the coasts of Kerala, Malaya and Java.

Today, as this great faith increasingly comes under attack from within and without and a tiny fringe pretends to speak on its behalf, it’s time to go back to basics. There has never been a greater need to revisit and reinvent Islam’s universal and humane message. We can confront historical injustices and grievances and the centuries of exploitation only by returning to the benevolent and just teachings of this faith. You cannot deal with injustice by greater injustice.

Only the force of justice can take on injustice. Targeting and victimisation of innocents to avenge historical wrongs is not just morally repugnant but also violates the fundamental teachings and the spirit of Islam. It’s time to revisit and rediscover our faith. It’s time to go back to basics.

Aijaz Zaka Syed is a Gulf-based writer. Follow him on twitter.com/aijazzakasyed