Like a crammer offering intensive revision classes before finals, No 10, Downing Street (office of the British prime minister) coordinated briefings over last week for MPs still uncertain about the prospective vote on military intervention in Syria against Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant). Available for consultation were Sir Mark Lyall Grant, national security adviser; Philip Hammond, the foreign secretary; and Michael Fallon, the defence secretary.

Understandable as it is that parliamentarians should be fully briefed before they walk into the division lobbies, their vacillation and, in some cases, moral paralysis is much greater than it needs to be. It is understandable that MPs should, for instance, seek reassurances about the 70,000 Syrian opposition forces said by the British government to be ready for ground battle against Daesh. But there is a deeper reticence in the Commons that exceeds the rational. This is the lingering spectre of Iraq doing its work.

That conflict and its long political prelude remain the prism through which any decisions regarding British military action are taken. The apparent inability of John Chilcot’s Iraq inquiry to produce its report — already five years late — is a perfect metaphor for the war’s resilient grip on the political class, and the Labour party in particular.

In Labour’s collective memory, Iraq is the war justified by intelligence twisted into headline-grabbing spin — intelligence that proved to be wrong. It is the conflict that was conducted by “sofa government”, in which Britain was supposedly America’s “poodle”. It was (MPs recall) the undoing of Tony Blair. It haunts leadership contests still (Jeremy Corbyn may have been a backbencher, but he was also national chair of the Stop the War Coalition). “Iraq” is shorthand for national shame in Britain. It infects the argument for military action of any kind. It is a madness in the blood of the body politic.

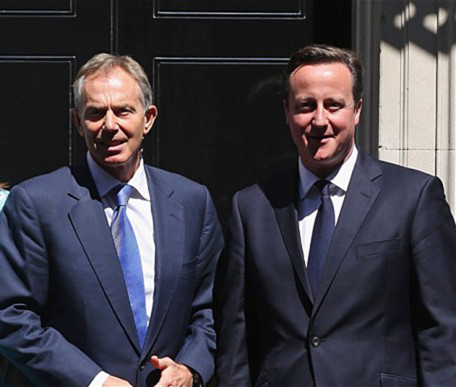

Last Thursday’s Commons debate on British military intervention in Syria the prime minister urged MPs to suspend all these inclinations. “Let us not look back to Iraq and 2003,” he said. “We have to separate in our minds, our actions and our votes the case in front of us now from what people feel they were told back in 2003.”

For those MPs who were in the Commons — or researchers, or union officials, or activists — when Blair made his famous plea for support, this is no easy task. It is like asking the French in the 70s to forget Algeria, or the Americans in the 80s to forget Vietnam. Quagmires can be psychological as wellas military.

Yet ultimately, they must be escaped. What has to be absorbed is how conspicuously unalike Cameron’s request is from Blair’s. The Iraq war, which began in March 2003 as Operation Iraqi Freedom, was an explicit example of the so-called Bush doctrine of pre-emption. This revolutionary approach to the justification of war had been declared in George W. Bush’s speech at West Point in June 2002. “We must take the battle to the enemy, disrupt his plans and confront the worst threats before they emerge... our security will require all Americans to be forward-looking and resolute, to be ready for pre-emptive action when necessary to defend our liberty and to defend our lives.”

This is emphatically not a war of pre-emption, but a war of self-defence that would not have troubled Augustine or Aquinas. We know already that the massacre of 30 British citizens in Tunisia in June was the work of a Daesh affiliate and a local cell, some of whose members had been trained in Syria. In the past year, according to Cameron, Britain’s police and MI5 have thwarted seven terrorist conspiracies to attack this country connected to Isis by direct action or inspiration. The disclosure that Daesh has a “dedicated external operations structure” established in Syria suggests strongly that the Paris atrocities were neither improvised, nor the last time a central urban killing spree will be attempted. The most rudimentary principles of self-protection demand that Britain take action against Daesh — including across the Syrian border.

Most reprehensible (and lazy) of all is to behave as if the conflict with extremist groups such as Daesh began with the Iraq war — excluding even 9/11 from the chronology. Blair himself has conceded that the failure to plan properly for reconstruction in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussain provided groups such as Daesh with an ideal context of lawlessness and resentment in which to grow. But it is historically illiterate to go further and suggest that the Iraq war is somehow responsible for the global surge in extremism.

One of Ken Livingstone’s finest moments as London mayor was the speech he gave in Trafalgar Square a week after the 7/7 attacks in 2005, celebrating the inability of the terrorists to turn Londoner against Londoner: “They failed, they failed totally and utterly.” So it was sad to hear him absolve those same killers on last week’s Question Time because — what else? — of Iraq.

“You can [absolve them]... They gave their lives.” This is, to put it mildly, a very generous way of describing suicide bombers who chose to self-immolate on packed public transport.

As I wrote a fortnight ago, the murderous ideology that sprayed bullets through the Parisian night on November 13 (and the 7/7 attacks, which killed 52 passengers who did not choose to “give their lives”) was embryonically visible in the flames that consumed The Satanic Verses a quarter century ago; in the first attack on the World Trade Center by Ramzi Yousuf in 1993; in the onslaughts on UN embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam in 1998; and in the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000.

Yes, of course Iraq added a new excuse, a new pretext, to a list of Islamist extremist grievances that range from the way women dress and behave to the rights of gay people (including the right to live, in Daesh territory) and the impiety of laughter and music. And — yes — Britain’s participation in the campaign against Daesh in Syria as well as Iraq will probably make them hate us more.

But they hate us pretty comprehensively already. When Daesh talks about “the crusaders”, it doesn’t don’t just mean today’s soldiers and their political leaders, but Godfrey of Bouillon (1060-1100) and everyone else in between.

For these extremists, Iraq is only a recent chapter in a very long book of history; they are now immersed in writing the next. The question facing MPs in this vote is whether Britain wants to pick up its pen too.