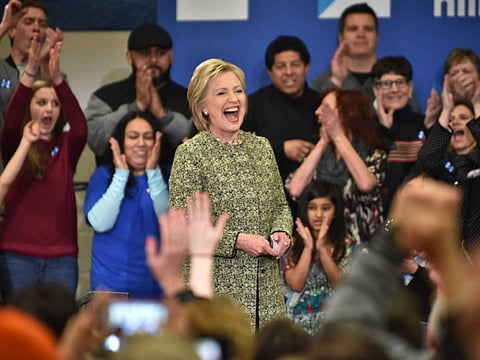

Hillary can unite Democrats

Cranking up the credibility quotient, a little help from Sanders and Warren and continued chaos in the GOP will make it possible for her to reunify her party

The battle between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders hasn’t turned into a playground brawl like the Republican campaign, but it has still pitted Democrats against each other, sometimes bitterly. Sanders has slammed Hillary as a candidate in the pocket of billionaire donors. Hillary has dismissed Sanders as a dreamer who can’t get things done. And some of their followers have been nastier than that.

After a divisive campaign, can Hillary win support from Sanders voters if she wins the nomination, as appears likely? She can and she will — but it’s going to take some work.

That’s a bitter pill for Sanderistas to swallow while their candidate is still slogging from state to state in pursuit of a long-shot comeback. Some are already organising a sullen resistance movement under the slogan “Bernie or Bust”. Its organisers are asking progressive voters to pledge not to vote for Hillary, no matter what. We’ve seen that kind of rearguard action before, and it almost never works. In 2008, a group of die-hard Hillary supporters pledged never to vote for Barack Obama; their mostly female group was called PUMA, an acronym for “Party Unity My ....” By election day, they were forgotten.

“People who come out to vote in primaries rarely sit out general elections,” noted Democratic strategist Mark Mellman, who isn’t working for either candidate. “Almost all Sanders voters will end up backing Hillary, assuming she gets the nomination.”

The most obvious reason: In the general election, Hillary will of course be running against a Republican, most likely Donald Trump or Ted Cruz, and Democrats will try to turn the election into a referendum on the GOP nominee, no matter which widely loathed name is on the ticket.

“Three months ago, the question for Hillary was: ‘What am I going to do to energise the [progressive] base’,” another Democratic operative told me. “That problem went away, thanks to Donald Trump.”

Some party strategists think Cruz, a beyond-the-mainstream conservative on social issues, would be even easier to defeat.

But the GOP candidate won’t be Hillary’s only asset. Once she’s sewn up the nomination, she’ll collect two endorsements that could sway sceptical progressives: One from Sanders, the other from Senator Elizabeth Warren (Democrat-Massachusetts.)

“There’s going to be no reluctance on his part” if Hillary wins, Sanders’ chief strategist, Tad Devine, told me. “He has said that Hillary Clinton is extremely well qualified to be president. Meanwhile, he’s competing, and it’s going to go all the way to the end of the primaries.”

Warren hasn’t said when she’ll make an endorsement, but she’s already thinking about how she could play a role in helping Hillary win — and, meanwhile, nudging Hillary towards more progressive positions.

“Economic populism is driving a lot of the debate,” a person familiar with Warren’s thinking told me. “She knows how to communicate and operate in that space. She takes seriously her role in helping Democrats get it right.”

Warren has already lobbied Hillary to support expanding Social Security benefits, a favourite progressive goal. Last month, Hillary promised not to seek benefit cuts and said she wants to increase benefits for the poorest beneficiaries.

Warren also helped persuade Hillary to endorse legislation banning Wall Street executives from accepting “golden handshake” payments from their firms when they get government jobs.

In fact, Hillary has been campaigning as a progressive all along — just as an incrementalist progressive, not a revolutionary like Sanders. She supports a higher federal minimum wage — just not as high as Sanders. She wants to expand financial aid to poor students and make community colleges tuition-free — but not all public four-year universities, as Sanders has proposed. She wants to expand President Obama’s health insurance program, but not convert it to a European-style “single payer” system, as Sanders wants.

She even has a campaign finance reform plan — although it’s not as radical as her rival’s. After her defeat in New Hampshire, she tried to sound as fired up as Sanders about that issue. “Senator Sanders and I both want to get secret unaccountable money out of politics,” she said. “You’re not going to find anybody more committed to aggressive campaign finance reform than me.”

However, Hillary’s biggest problem with progressives isn’t her policies; it’s her history. Polls have long shown that many voters, including Sanders backers, don’t quite trust her. In New Hampshire, voters who ranked honesty as a high priority favoured Sanders over Hillary 92 per cent to 6 per cent.

Clinton knows that.

“I understand that voters have questions,” she told an interviewer in January. “I think there’s an underlying question that maybe is really in the back of people’s minds, and that is: ‘Is she in it for us or is she in it for herself?’ I think that’s a question people are trying to sort through.”

A credible answer to that question, a little help from Sanders and Warren, and continued chaos in the GOP will make it possible for Hillary to reunify her party for the fall campaign.

Doyle McManus is Washington columnist for the Los Angeles Times. He has been a foreign correspondent in the Middle East, a White House correspondent and a presidential campaign reporter.