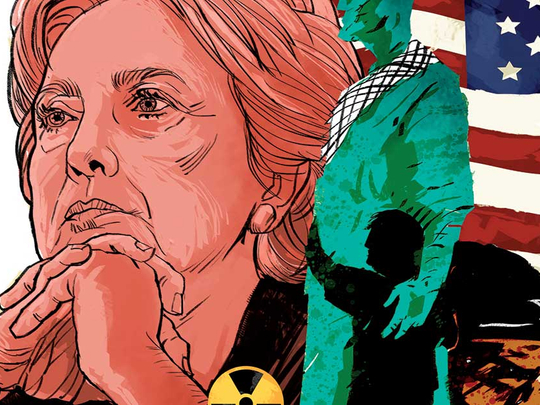

As Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign ramps up for the general election contest against Donald Trump, much negative and positive attention is focusing on her time as United States secretary of state, from 2009 to 2013.

Hillary has more than two decades of involvement in international affairs, first as first lady, then as a senator, and then as secretary of state. This provides a wealth of information to help voters and observers understand how Hillary will approach the Middle East if elected president. Her book Hard Choices, published in 2014, provides her own account of her time as secretary of state. She left office before significant recent events, including the nuclear agreement with Iran and the rise of Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), though she witnessed the sowing of the seeds of both. Nonetheless, the book, combined with other sources about her time as secretary, provides useful insights now that she is a leading candidate for president.

Hard Choices is an appropriate title for these memoirs, as Hillary is a quintessential pragmatic diplomat who believes in balancing options and making the hard choices that she thinks will lead to the best outcomes. As secretary of state, she embraced the idea of “smart power”, which sought to break down an old division between “hard” (military) and “soft” (diplomatic, economic, cultural) power. “For me, smart power meant choosing the right combination of tools — diplomatic, economic, military, political, legal, and cultural — for each situation,” she writes. This is an ongoing theme in her book: “Engagement and pressure. Carrots and sticks.”

She also rejects the dichotomy of “realists” versus “idealists”, viewing herself as “perhaps an idealistic realist”. She suggests that there is often less tension between core national interests and values such as democracy and human rights than is commonly perceived; another major theme in the book is that respect for human rights is important to long-term stability. At the same time, she recognises that US leaders sometimes must make “difficult compromises”, and she does not apologise for this.

The 2011 Arab uprisings particularly challenged Hillary’s desire to balance security interests with American values, and to follow clear principals while allowing for differences between countries. Hillary took a gradualist approach, calling for caution when some other advisers wanted the US to more openly support demonstrators, particularly in Egypt. If elected president, she probably will disappoint activists who seek significant reform in countries that are important US partners. Indeed, she feels that events vindicated her early concerns that removing leaders too quickly would lead to instability or, in Egypt, to Muslim Brotherhood control.

At the same time, throughout her book and in other sources, Hillary is clear in her belief that repressive governments who fail to meet the political and economic needs of their people are inherently unstable in the long term. She prefers gradual reform to revolution, but leaders of Middle Eastern countries should not expect unquestioning support from a President Hillary Clinton. She is likely to push for political and economic change, albeit in a more cautious manner than many reformers might want. Furthermore, in states that are not US allies, she may be more willing to encourage political opposition. In her book, she expresses some regret, with hindsight, that Washington did not do more to support Iranian demonstrators in 2009.

Hillary is also willing to intervene in conflicts, but whether and how depends on her interpretation of specific conditions in a conflict. As secretary of state, she was more willing than US President Barack Obama to intervene, and as president, she would likely be more assertive.

In Libya, she cautiously supported US intervention, after determining that she thought the Libyan opposition was sufficiently organised and motivated to have a decent chance of leading a post-Muammar Gaddafi transition. Along with Obama, she also felt it was necessary to have broad international support and she helped to secure United Nations Security Council approval and alliances with European and Arab states.

In Syria, early in the conflict, she also tried to gather international support to stop the Bashar Al Assad regime’s violence, though she felt that Russia obstructed these efforts at the UN. She also advocated for Washington to train and arm a group of vetted opposition fighters, with the goal of placing enough pressure on Al Assad to lead to viable negotiations, but Obama rejected the idea at the time. The proposal, however, was a classic example of Hillary’s approach — applying military and economic force in order to reach the eventual goal of a political solution.

She views the US approach to Iran at the time as exactly that — applying pressure through all possible US tools in order to force Tehran to engage in serious negotiations. She is proud of her role in uniting an international coalition to apply harsh sanctions on Iran, viewing this as key to bringing Tehran to the table. She left office before the completion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) but has publicly supported it while also calling for strict implementation.

Overall, Hillary is likely to be tough on Iran while continuing to implement the JCPOA. In her book and in campaign speeches, she appears to genuinely view Iran, as led by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamemei, as “intransigent and untrustworthy”, a belligerent force for instability in the region. In her book, she expresses concern for the hardships that Iranians endured under sanctions, but blames those on the Iranian regime. If she becomes president, Gulf states do not need to worry that she has any personal bias in favour of Iran or interest in developing Iran into a new US partner. At the same time, she is very unlikely to turn her back on the JCPOA as long as she believes that it is achieving the goal of preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

If she becomes president, Hillary is likely to disappoint many in the Middle East with her approach to Israel and Palestine. As first lady, she once called for the creation of a Palestinian state before it was official US policy. However, during her days as senator for New York and as secretary of state, she supported the standard US approach on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — which is informed more by Israeli perspectives than by Palestinian views.

Hillary appears to have some real empathy for the difficulties that Palestinians face and she continues to call for a two-state solution. At the same time, she mostly writes about the conflict from the perspective of Israel’s concerns. For example, in writing about the Gaza crisis in November 2012, she repeatedly says that Israel has the right to defend itself against rockets fired from Gaza, while mostly ignoring the highly disproportionate death tolls. She blames Yasser Arafat for rejecting the “Clinton Parameters” in 2000/2001 without mentioning Israel’s reservations.

Hillary calls for a pragmatic blend of military, economic and diplomatic pressure combined with efforts to advance peace, freedom and prosperity. As she acknowledges that she and the US have made mistakes. But at least Middle Eastern leaders have a pretty good idea of what to expect from Hillary, while Trump is a wildcard.

Kerry Boyd Anderson is a writer and political risk consultant with more than 13 years’ experience as a professional analyst of international security issues and Middle East political and business risks.