Governments love to exaggerate problems

Despite what politicians say, most people are richer and freer than they have ever been

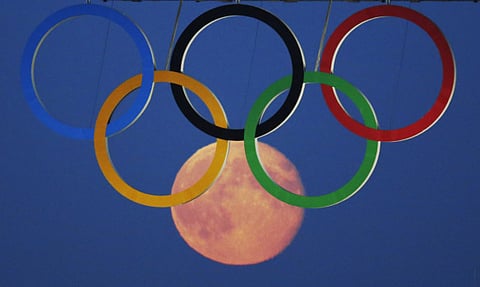

The Olympic motto ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’ strikes a depressing contrast with a British economy showing none of these characteristics. Behind the jubilation lies a horrible feeling that with the Games ending, Great Britain be back to the grim reality: the Leveson Inquiry, the still-unravelling budget and the slow-motion implosion of global capitalism.

There ought to be a name for this feeling: political myopia. It can afflict anyone who confuses what politicians do with what’s happening in the country, or what they say with what is going on in the world. The world has never been richer, healthier, freer or more equal than it is today. The idea that the world is going to hell has been hardwired into the psyche of most political leaders throughout recorded history.

Archbishop Wulfstan of York declared in 1014 that “the world is in a rush and is now getting close to its end”. Similar prophecies exist now: that the environment is being despoiled, climate chaos is claiming an ever-increasing number of lives, the rich world is leaving the poor to rot and our energy supplies are soon to be exhausted.

Take global poverty. Britain has signed up to the so-called Millennium Development Goals, set in 2000. It was the beginning of boom times for the overseas aid industry, despite its woeful track record.

The first goal was to halve the proportion of the world’s population living on a dollar a day by 2015 — an undeniably noble aim. Earlier this year, the World Bank made an astonishing discovery: the target had actually been met in 2008, seven years ahead of schedule.

This staggering achievement received no fanfare, perhaps because the miracle had not been created by western governments, but by the economic progress of China and India. Their embrace of capitalism had invited a flow of trade and investment, which was not halted by the crash. While the West was using cheap debt to fake economic progress, the developing world has been doing it for real.

The so-called Gini index, the standard measure of global inequality, fell steadily during the boom years and has continued to decline during the crash. And little wonder, at a time when the Indian economy is literally growing faster in a week than Britain does in a year. The economic aid that Britain gives to India is now the same size as India’s own international aid budget.

India has hideous problems, as does the rest of the world. But each year, even during the crash, the UN Human Development Index has hit new records. We are living in an era where the world’s problems are being outweighed by its breakthroughs. As countries grow richer, they grow healthier.

Life expectancy keeps setting new records, for both the rich and the poor world, as developments in medicine advance rapidly. Malaria deaths peaked in 2004 and even Aids deaths peaked five years ago.

Anthony Fauci, America’s leading authority on the disease, said last month that there could be an “Aids-free generation” in the reasonable future. “We have no excuse, scientifically, to say we cannot do it,” he told an Aids conference in Washington. Such a statement would have been unimaginable just a decade ago.

No resource crunch

Aids remains the world’s most lethal contagious disease, responsible for almost two million deaths each year. But medicine is catching up with it. We can now dare to believe that Aids will go the way of smallpox. A healthier world means a rising population. This, in turn, leads to neo-Malthusians worrying about how the planet won’t have enough resources for all of us — but history proves them wrong.

The great British economist, William Stanley Jevons, warned in 1865 that the economy was on the brink of collapse because the coal would run out. Oil was used instead, and everything changed. In the last five years a new energy source, shale gas, has halved American electricity prices. The thousands of British wind turbines may be rendered redundant by shale deposits discovered in Lancashire, which could yet turn Blackpool into the Dallas of England.

And might the consumption of all this newly mined fossil fuel doom us anyway, via global warming? The truth is that the world’s fossil-fuel consumption is falling, mainly due to more efficient cars and factories. Nor is warming synonymous with doom.

Scour the raw data of the UK government’s climate change ‘risk assessment’ (as I did) and you find that a warmer Britain will mean, on average, 11,000 fewer deaths each year by 2050 because fewer pensioners will die from the cold. But do not expect to find this point made in any official report. The Environment Department is there not to give impartial advice, but to scare people.

Conjuring up crises

The purpose of government is to solve problems, which is why it is prone to exaggerating them. It is easy to conjure up a crisis if you extrapolate a trend far enough into the future. It’s always pointless: as the Yiddish proverb has it, man plans and God laughs. History is dictated by the unpredicted, and a government’s best hope is to give people the security and freedom to improve the country in the way a bureaucracy never could.

The great irony of politics is that those nominally running the country are often the last to work out what direction it has taken. This was, in a roundabout way, the point the Queen made when she addressed the United Nations two years ago. She had witnessed incredible change, she said, and much of it for the better. But weekly audiences with a dozen prime ministers seem to have left her with a clear idea about who makes things better.

“Many of these sweeping advances have come about not because of governments, committee resolutions, or central directives — although all these have played a part,” she said. The improvements came simply “because millions of people around the world have wanted them”. The Queen was too polite to spell it out: don’t listen too hard to the politicians. It will just depress you. They do their best, and sometimes even help things, but play a minor role in the development of nations.

A country is not shaped by manifestos or five-year plans, but by the courage and ingenuity of its people. And the Olympics, a glorious festival of human achievement, is far closer to what’s really happening out there.

— The Telegraph Group Ltd, London 2012

Fraser Nelson is editor of The Spectator.