How bad is bad? As the results of Germany’s three regional elections came in, the losses suffered by Chancellor Angela Merkel’s centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) were described as “dramatic”. In a vote widely seen as tantamount to a referendum on the welcome Merkel had extended to Syrian refugees, the verdict was interpreted as an unequivocal thumbs-down, with electoral momentum passing — almost unthinkable in Germany — to the xenophobic far right. The CDU was being punished for an unpopular policy devised and articulated, with uncharacteristic audacity, by its leader.

How bad the outcome really was for the CDU and, by extension, for Merkel, however, depends to a large degree on your expectations. The most extreme forecast had been that the CDU would be trounced to the point that Merkel would have to consider her position. That did not happen. The CDU was not erased. The chancellor has been weakened, but she lives to fight another day.

At the other extreme, there had been a hope — albeit faint — that voters would rally around Merkel almost as an act of defiance and an expression of confidence in a new, more modern, more diverse and more generous Germany. That did not happen either. The anti-migrant party Alternative fuer Germany (AfD) significantly increased its vote, reaching double figures in all three states that voted on Sunday and qualifying for representation in the regional legislatures. So Germany, for all its history, is not immune to the far right after all.

In the event, though, Germans voted more cannily, and more realistically, than first reactions gave them credit for. And the effects of the Far-Right vote were different in each region. In Saxony-Anhalt, a poor state in the east, the AfD overtook the Centre-Left Social Democrats (SPD) to take second place to the CDU. In Baden-Wuettemberg, the Greens were the main beneficiaries of Merkel’s woes, while in Rhineland-Palatinate it was the SPD, and the fortunes of the regional CDU leader, Julia Klockner, who is seen as a possible heir to Merkel, who suffered a blow.

In the end, neither the flight from the CDU nor the embrace of AfD was so whole-hearted that it transformed the complexion of German politics. In each state the major party remains the same, but the coalitions will have to be reconfigured. Nor is there the slightest prospect of the AfD entering government at the regional level. It is still, for the time being at least, a protest party.

The AfD vote, however, highlighted two problems — one endemic to German politics, the other more immediate and of Merkel’s own making.

The voters — constituting around 12 per cent of Germany’s electorate — sent Merkel a clear warning in advance of next year’s national elections. By no means all resorted to the AfD to make their feelings known. Outside the former East, many chose to support the party — the Greens, or the SPD — that would most effectively clip the CDU’s wings. That is the mark of a well-informed and practical electorate, but it also illustrates a difficulty with the system.

Merkel heads a “grand coalition” made up of the CDU/CSU and SPD, which essentially means that there is no official opposition party at national level, and no “respectable” outlet for voters with misgivings about Merkel’s policies. Centre-Right (the CDU/CSU), Centre-Left (SPD), further Left (Die Linke) and the Greens are all, nominally at least, in favour of a liberal line on migration. This leaves the Alternative for Germany as the only party representing another view — and many Germans will think twice before voting for it.

Some of the loudest official misgivings about Merkel’s welcome for refugees have come from ministers in her own party, notably Finance Minister Wolfgang Schauble, and from the CDU’s Bavarian sister party, the CSU — because Bavaria bore the brunt of the early refugee arrivals.

Last Sunday’s election results give Merkel and her government some time and some space to demonstrate that they can get to grips with the considerable task they have taken on before they face the voters again. They must start to integrate the million or so newcomers they have already accepted, improve the processing of those yet to come, and persuade other European countries to do more.

But the lack of any formal opposition channel is a handicap. It may mask the true extent of popular discontent, which is increasingly to be heard in private conversations — which is where the more immediate problem comes in: The agreement Merkel struck with Turkey providing for controls on new refugee arrivals and repatriations.

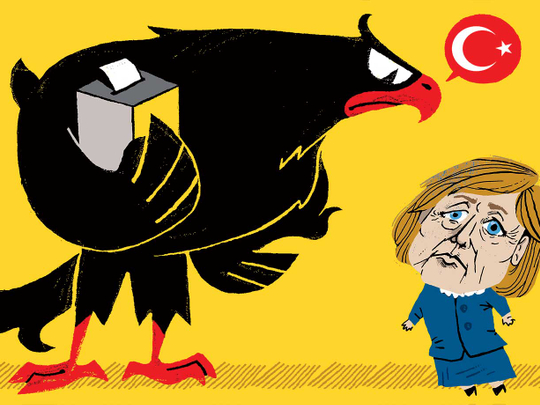

Merkel surely hoped that the deal — reached just days before the elections and underwritten by the European Union as a whole — would buy her time. Whether it had any electoral effect is unclear. Even as the polls closed in Germany on Sunday, however, its liabilities were being graphically illustrated.

With the practicalities of the European Union-Turkey deal being finalised — including the politically unpopular lifting of visa-restrictions — more than three dozen people were killed by a car bomb in Ankara, the latest in a wave of attacks. The Turkish government’s response to these attacks has been to restrict civil liberties, close one of the most popular newspapers and escalate its campaign against Kurdish forces on and around its borders.

Is this a country with which the European Union in general and Germany in particular, can, or should, be doing business? Is it right to regard Turkey as safe — for its own citizens, let alone for refugees? Merkel may have bought her government time, but at what cost? Seen in a wider perspective, she may have fended off one local crisis, by embroiling Germany in another that is far wider and far harder to control.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Mary Dejevsky is a writer and broadcaster and a member of the Valdai Group and a member of the Chatham House think-tank.