It’s pretty safe to say that 2016 was not the year of the woman.

We can start with the ridiculous tantrum the maniverse threw when the new “Ghostbusters” were women, we can discuss the way female athletes who crushed the Summer Olympics were treated as second-tier celebrities in America. And we can continue wondering how one of the most experienced candidates to run for president won the popular vote, but was edged out by a narcissist who bragged about grabbing women.

That all happened last year. And women took a deep breath, looked at that cracked, glass ceiling overhead and decided to fight on.

Then Vera Rubin died.

Who’s Vera Rubin?

Oh, she’s just the scientist who verified the existence of 90 per cent of the known universe.

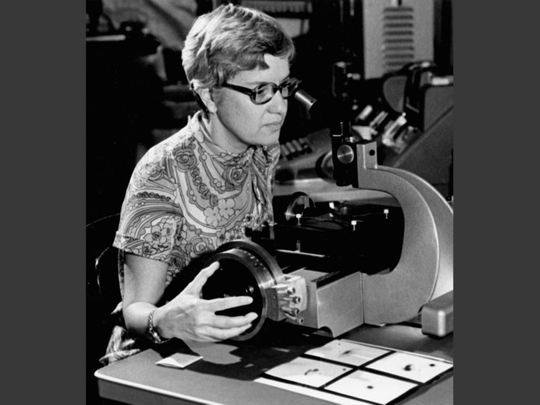

Rubin is the mother of dark matter. She unlocked a mystery that astronomers have been puzzling over for nearly 100 years.

The work she did — while raising four children, while being dismissed by male colleagues, while being forbidden from presenting her work at conferences — was one of the great scientific advances of our time.

Yet Rubin, who died on Christmas at 88, was never awarded the Nobel Prize that she deserved. She never became a household name. Even her hometown paper, the Washington Post, didn’t put her obituary on its front page, though it did so for the actress who played a fictitious denizen of the stars — Princess Leia. The person who actually discovered all those galaxies, far, far away? Rubin’s obituary ran inside the Metro section.

This isn’t a knock on Carrie Fisher. She was the 1.0 of feminist movie heroines in Star Wars. Her role was empowering for an entire generation. Beyond Leia, she was a great writer and a brave chronicler of her substance-abuse and mental health problems.

But the attention Fisher commanded compared to Rubin, who did such groundbreaking work against such daunting odds, reminds us of what most of society still expects of women.

Actresses? Cool. We’ll embrace that.

But scientists? Record-breaking athletes? Leaders?

Does. Not. Compute. Still! In 2016.

From the lab to the Olympic podium to the Oval Office, America still has a problem with women when they’re good at the things men have long reserved for themselves. That’s where you’ll find the ugliest sexism. Here’s how Tim Hunt, who won a Nobel Prize in 2001 for his work on protein molecules, explained the problem with “girls” in his world. “Three things happen when they are in the lab ... You fall in love with them, they fall in love with you and when you criticise them, they cry,” he said.

Oh really?

Too bad Hunt and Rubin weren’t in the same scientific field. Rubin was as tough as nails. Her high school teachers told her to avoid science. She didn’t listen. After graduating as the only female astrophysicist in her Vassar 1948 class, Princeton University wouldn’t admit her for graduate studies because of her gender. Their loss. Rubin went to Cornell instead, then earned her Ph.D. at Georgetown University.

All while raising four children.

When she showed up with a one-year-old to present a paper once, the male scientists chastised her. Oh well, she said. And then she went on to blow them all away by verifying the dark matter they’d been trying to figure out for years, the work they had struggled with while their wives stayed home with the children.

It was back in the 1880s that the Harvard Observatory was dissed for using women to do scientific research, for subjecting “a lady to the fatigue”. The director boldly hired the all-female research team because, well, he ran out of money to pay men. And what did the unpaid women do? They created a map of the cosmos that is still used today, a triumph chronicled in Dava Sobel’s book, The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars.

For centuries, women have been turned away, chased out, sexually harassed, unpaid or underpaid when they ventured into male-dominated worlds. Think things have changed? Female scientists talk about being sexually assaulted by professors and denied promotions after asking for equal pay.

But they work on.

Just last year, female scientists were part of some of the biggest advances in science and technology. They helped a quadriplegic play guitar, they found a walking fish that is an evolutionary missing link, they helped pinpoint the molecule that helped single-celled organisms evolve into multi-cellular organisms about 800 million years ago and they were a huge part of the team that just announced the creation of the first successful Ebola vaccine.

Year of the Woman? Maybe that’s not the headline.

Another year women did amazing things despite haters?

That sounds about right.

Or how about we just call it, The Year of Vera Rubin?

— Washington Post

Petula Dvorak is a columnist for the Washington Post.