The National Museum of Immigration History in Paris is a fascinating place to visit at the moment, against the backdrop of fierce debates over whether to clamp down on new arrivals. The tale told here about the experience of modern immigration to France is rather different from the one told at Ellis Island — and different, too, from the one told by France’s more alarmist immigration opponents. The museum is housed in the former Palace of the Colonies, built for the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition - a huge, unironic celebration of the wonders of colonialism that lasted six months, sold 33 million tickets and had a “human zoo.”

The permanent exhibit begins its story around 1851, when tens of thousands of skilled workers and managers came from Britain to help France industrialise. Then came labourers from Belgium, to man the new factories; Jews from Tsarist Russia, in flight from pogroms; and Polish elites, after their so-called Cadet Revolution against Russian rule was crushed. Most of these people were, according to the curators, warmly embraced. Larger waves of Italian labourers were less welcome. Their devout Catholicism seemed disturbingly ostentatious to a relatively new Republic founded on militant secularism. On one occasion in 1893, dozens of Italian workers were killed in an anti-immigrant riot.

Later, during the First World War about 140,000 Chinese workers were shipped in to help in the war effort, after which came Armenians escaping genocide in Ottoman Anatolia and White Russians fleeing from the Bolshevik Revolution, Spaniards from General Franco, Portuguese from Prime Minister Antonio Salazar, and Hungarians from the Soviets. North African Muslims — the Italian Catholics of today — started arriving toward the end of the 19th century, supposedly as guest workers, but in larger numbers once Algeria’s eight- year war of independence began in 1954. Some brought along brutal memories of their French colonial masters. The French themselves weren’t happy about the guerrilla-style war that forced almost one million European settlers in North Africa to return home.

The front page of the October 23, 1957, edition of France Soir reads much like what one might hear today from a supporter of Marine Le Pen’s hard-right National Front. Under a bigger story about a terrorist attack in Algeria, the headline reads: “A belt of bidon-villes around Paris.” Bidonville is the French word for slum, first used to describe urban settlements around cities in North Africa.

“We don’t dare go out at night anymore,” said a (presumably white) resident of the equivalent of today’s banlieues (the high-rise suburbs where poorer North African families tend to live). Yet the immigrants probably had more cause for fear. In 1961, when some 30,000 of Paris’s new citizens from Algeria demonstrated in favour of independence, police arrested 11,000 and killed at least 40, according to the long-classified and still-disputed official figure. This kind of history leaves scars.

Economic crisis worsening resentment

Even so, the years 1955-1974 were mainly good for immigrants. In France after the war, labour was scarce, economic growth strong and there was plenty of work. Tensions didn’t flare in earnest until the 1970s oil crisis triggered recession, and then things went quickly downhill. Today, once again, economic crisis is exacerbating resentments on all sides.

The difference in 2015 is that the young Frenchmen from North African families who bristle at Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) are no longer immigrants. They’re wholly French, but don’t see much of a future for themselves. For a few — like the two Kouachi brothers who carried out the attack on Charlie Hebdo — jihadists offer a new identity as warriors in a global Muslim struggle against the infidel West and Israel.

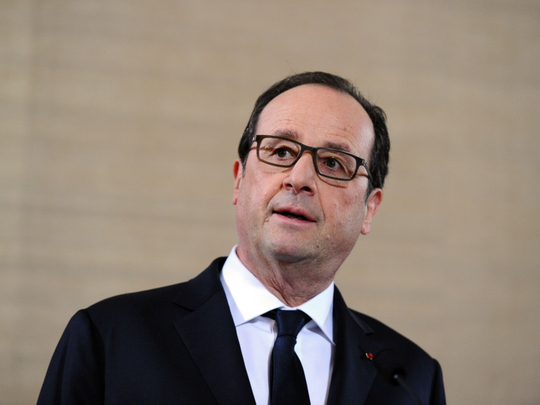

Cutting off new immigration wouldn’t change that. But some politicians nevertheless claim that last week’s attacks prove the inflow of foreigners must stop. The immigration museum itself was — until President Francois Hollande made the effort a few weeks ago — the only one in France not officially inaugurated, despite being open for business since 2007. That says something about the ambivalence and sensitivity France has often had toward immigration.

It also makes Hollande’s inauguration speech last month rather impressive. In it, the president spelt out the benefits that immigrants have brought to the country, and the data showing that France — contrary to the scaremongering of the National Front — currently has one of the lowest per capita immigration levels of any European nation.

Last week, French Prime Minister Manuel Valls said that without its Jewish population, France wouldn’t be France, and that’s true. It’s true of France’s other immigrants, as well — from those once-pesky Italian Catholics to Algerians — however difficult the integration process.

— Washington Post

Marc Champion writes editorials on international affairs for Bloomberg View.