Barely a month after Al Qaida’s devastating September 11, 2001, attack on the Twin Towers in New York and on the Pentagon near Washington, a maddened and enraged America attacked and invaded Afghanistan. The aim was to punish Afghanistan for giving shelter to Al Qaida — a radical Islamic group responsible for the unprecedented terrorist assault on the US, which killed nearly 3,000 people.

Hell bent on revenge, the then US president, George W. Bush, proclaimed a “global war on terror”. The 21st century thus began with a great outburst of violence and counter-violence, which a dozen years later shows little sign of abating.

The American war on Afghanistan shattered much of that country, killed hundreds of thousands of its citizens and is still unfinished a dozen years later. The US and Britain then attacked Iraq in 2003. The reasons for doing so were fraudulent because Iraq had nothing to do with Al Qaida’s terrorism. However, pro-Israeli neocons in the US administration seized the chance to destroy a leading Arab country, which might have challenged Israel’s regional hegemony. By the time the US finally withdrew in 2011, Iraqi civilian casualties were estimated at well over one million and material destruction immense. As the country wrestles with the painful task of political and physical reconstruction, it has fallen victim to Sunni-Shiite quarrels, which threaten to tear it apart once again.

Under President Barack Obama, the US has continued to kill Muslims it considers hostile — in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and other places across the globe, usually resorting to strikes against distant targets by pilotless armed drones. Large numbers of innocent civilians have been among the casualties, inevitably stoking violent anti-American feeling among relatives and friends of the victims.

These violent events across the Middle East — which are now spreading to the Sahel in North Africa — have dominated the first years of this century. One way or another, they have all been triggered, and been publicly justified, by Al Qaida’s 9/11 assault on the US. Yet, an inescapable fact is that a great many victims of these retaliatory wars were innocent Muslims, who had nothing to do with Al Qaida, but were swept up in the security frenzy of the time.

Over the past dozen years, many Muslims in Britain and America have faced discrimination, harassment and years of incarceration without trial just because they are Muslims. The secret war against them has passed largely unnoticed and unreported, largely because opinion is still outraged by Al Qaida’s violence. However, their plight — and the devastating impact it has had on their wives and families — caught the attention and aroused the conscience of the British writer Victoria Brittain. Her book, Shadow Lives, which examines the painful lives of these victims of counter-terror, is a heart-wrenching work to which she brings the passion and the careful investigative skills which made her reputation on the British daily newspaper, the Guardian.

With barely suppressed anger, she describes how, after 9/11, Bush and British prime minister Tony Blair launched ‘what was effectively an anti-Muslim crusade’ — including the right to arrest, indefinitely detain or deport anyone, even if they had committed no crime, as well as massive surveillance of mosques and Muslims. Britain, America’s close ally, was swept up in the hysteria which was to condemn many an innocent Muslim to long years of incarceration and their families to untold misery.

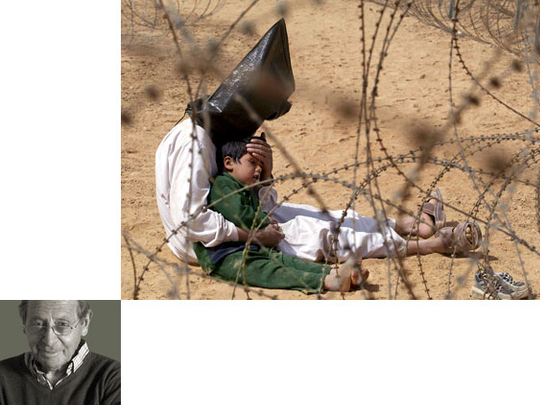

Guantanamo Bay in Cuba was, Victoria writes, ‘the centrepiece of the reaction to 9/11 and remains the symbol of how half a century of international conventions on torture, prisoners’ rights, rendition and other aspects of international law were simply over-ridden by the US government and its allies’. In the name of national security, anti-terrorist laws were passed which meted out gross injustice. Thousands of men were captured, many of them entirely innocent, in what she describes as ‘a vast fishing expedition across the Middle East, Pakistan and Afghanistan and from Bosnia to Gambia’. Prisoners were sent to Guantanamo where they were held beyond the reach of US law, without habeas corpus, in conditions that were flagrant violations of international law. The Geneva Conventions were set aside. Torture was widely and systematically practiced. She describes how, in Guantanamo, men were ‘stripped naked in front of females, held in freezing containers, kept awake for as long as 20 hours a day’ and were subjected to repetitive interrogation. Her book is, in fact, a passionate indictment of the cruelty and stupidity of the war on terror.

Most of the men at Guantanamo were held there on very slight evidence. They were victims of a ‘steamroller of propaganda’ by the US and UK governments and their media allies. Stoking fear of Muslims had become a profession. Even before 9/11, Arabs and Muslims in the US were victims of what the author calls ‘a general manufactured climate of fear ... often linked to efficient and well-funded pro-Israeli lobbyists’.

Of Victoria’s many painful case studies, I have space to mention only two. Gassan Elashi was chairman of America’s largest Muslim charity, the Texas-based Holy Land Foundation for Relief and Development. In July 2007, he and four colleagues from his Foundation were charged with ‘material support’ for Hamas. They had sent some $12 million (Dh44.13 million) to Gaza — earmarked for orphanages and community welfare groups. Although the groups they were helping were not on any government terrorist list, the prosecution claimed they were fronts for Hamas. Elashi was sentenced to 65 years in jail. The impact on his family was devastating.

Sami Al Arian, a professor of engineering at the University of South Florida and an outspoken campaigner for Palestinian rights, was indicted in 2003 on multiple counts of ‘material support for terrorism’. In a 2006 trial, after nearly three years in solitary confinement, the jury acquitted him of half the charges, while they were deadlocked on the others, with ten jurors to two wanting to acquit. He took a plea bargain on one count, agreed to deportation and should have been freed the following year. Yet, he was charged with criminal contempt when he would not testify in another trial. In 2009 he was released to house arrest, where in three years he was allowed to leave his apartment twice — for his daughters’ weddings.

In Britain, too, many men were arrested after 9/11 as part of a worldwide intelligence swoop on Muslims. They were assessed as ‘risks to national security’ and held for years in high-security prisons on secret evidence that was not disclosed to their lawyers and about which they were never interrogated or charged. As Victoria comments: ‘Indefinite detention felt like torture to them and as life suspended for their frightened wives’.

Shadow Lives is an important book which will awaken righteous rage in many readers — or reduce them to tears.

Patrick Seale is a commentator and author of several books on Middle East affairs.