European Union (EU) leaders convene on Thursday for a crucial two-day summit, which will seek to end what European Council President Donald Tusk has called “the days of irregular migration” to the continent. The crisis is perhaps the No 1 one political challenge facing the EU, right now, and the meeting comes five years since the start of Syria’s civil war, which has been a primary driver of the refugee flows.

Since the outlines of Europe’s migration deal with Turkey were released, they have been criticised on moral, legal and practical grounds, including by the United Nations. Nevertheless, there is growing pressure on the continent’s leaders to secure an agreement, which they assert could stabilise the currently chaotic mass-migration, while potentially maintaining Europe’s generous asylum system.

Growing popular discontent with the migration status quo was illustrated on Sunday with the results of three German regional election results, which saw the new nationalist, anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) Party making striking gains, and the ruling-Christian Democrats losing ground in Baden-Wuerttemberg and Rhineland Palatinate, amid unease over Chancellor Angela Merkel’s so-called “open door” policy. And Germany, which took in around one million migrants last year, is not the only country where the issue is growing in salience.

French President Francois Hollande already is limiting his country’s intake of Syrian refugees, following last year’s attacks in Paris. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister David Cameron wants a deal to help him make his case to the United Kingdom electorate that the EU ‘works’, as the June 23 ‘Brexit’ referendum nears.

In effect, the outline deal would seek to turn Turkey, formerly a European bulwark against the Soviet Union, into a post Cold-War buffer against migration from the Middle East. Already, some two million Syrians live in Istanbul alone, which underlines that the country has borne the brunt of migration flows. In turn, Turkey has become Europe’s most porous ‘border’ to irregular migrants (those arriving outside normal transit procedures) with most of the 1.2 million who arrived in the EU last year coming via the country.

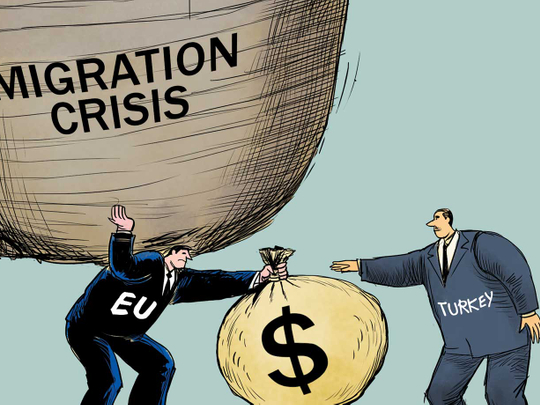

Under the terms of the controversial outline deal, new irregular migrants crossing to Greece will be returned to Turkey, with Brussels footing the bill. In return, the EU would admit vetted Syrian refugees directly from Turkey — one for each Syrian asylum seeker Ankara took back from Greece — in what Eurosceptic critics have terms a “migration merry-go-round”.

The idea is that migrants would be chosen who had waited patiently in Turkey, not those paying smugglers for a risky sea crossing. Those selected would then be sent, in principle, to EU countries that agreed last year to take in a quota. In return for Ankara’s acceptance, plans would be accelerated to ease access to the EU for Turkey’s approximately 75 million citizens, with a view to allowing visa-free travel later this year, despite the fact that the country has yet to meet many preconditions, including introduction of biometric passports. This would infuriate many Europeans opposed to such a move, especially of a Right-wing disposition, because it will inevitably increase Turkish migration to the EU.

Ankara would also receive payment of around 3 billion euros (Dh12.27 billion), with the possibility of additional funding — Turkey is believed to want around ¤6 billion in total. Moreover, preparations will be made on opening of new chapters in talks on EU membership, including potentially chapters 23 and 24 on the thorny issues of justice and the rule of law. Ultimately, any accession is still at least 5-10 years away with Ankara some distance from democratic standards needed to gain membership.

Partly because of this, and the apparently growing autocratic tendencies of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, there has been significant backlash to the outline deal, and it is highly uncertain that Tusk’s pledge can be fulfilled that the age of irregular European migration is over. For instance, a leaked document from Eurojust, the EU’s judicial cooperation agency, reportedly asserts that the emerging agreement would be exceptionally hard to implement, in part because Ankara does not have the political will nor infrastructure to deliver it.

The report notes that “Turkey has no specialised border or migrant forces, lacks sufficient visa legislation and has no independent judiciary”. It also asserts that Ankara has no fit-for-purpose system in place for expelling migrants who are “freed after a few days” and simply told to leave the country.

As well as practical concerns about the plan, there are wider legal and moral concerns too. On the former front, the UN amongst others has questioned the basis of the proposed mass deportation which it asserts could mean illegal “collective and arbitrary expulsions”.

There are also doubts over whether Turkey can truly be declared a “safe” country for asylum-seekers, the EU definition of which is a state adhering to the Geneva Convention, to which Ankara does not fully comply. Turkey formally applies that 1951 convention only to those fleeing war or persecution in Europe. This has understandably given rise, on the moral front, to concerns with Austrian Interior Minister Johanna Mikl-Leitner admitting that “I ask myself if the EU is throwing its values overboard”.

Even if the outline deal can be concluded, the migration issue will not be removed from the EU ‘in-box’. For instance, focus will be needed on helping forge a lasting peace agreement in Syria, while plans will be needed to stop migrants using other routes, including from Albania or Libya to Italy. The death rate in 2015 on this sea route, based on data from the International Organisation for Migration, was around 1 in 20, compared to approximately 1 in 1,000 between Greece and Turkey.

Taken overall, EU leaders will double down on concluding a deal on Thursday, despite significant criticism of the outline. As Sunday’s German elections underline, political pressure is growing to finalise agreement, however imperfect, to try to stabilise currently chaotic mass-migration to the continent, while potentially preserving Europe’s generous asylum system.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.