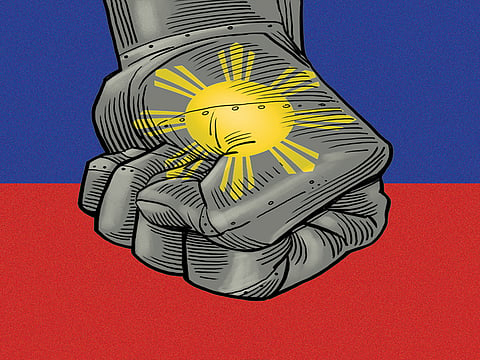

Don’t compare Trump and Duterte

It’s easy to connect their loud-mouthed populism, but the rise of this unpredictable man to the Philippines’ presidency is more of a threat to the world

Rodrigo Duterte will be the next president of the Philippines. Duterte only managed to file his candidacy on the last possible day — he was supposed to lack the money and political machinery required for a presidential run — his rise has understandably surprised many. Undoubtedly, the first president from the southern conflict-stricken island group of Mindanao — where a long-running insurgency rages, as well an increasingly violent battle with the Communist New People’s Army — he also believes himself to be “the first president from the Left”. Dubbed “The Punisher” by Time as far back as 2002, there have been comparisons to Donald Trump and Dirty Harry. But unlike Trump, Duterte now wields considerable national and international clout and has for some time in his own neighbourhood. Unlike Trump, he is an experienced political figure.

We know little of what Duterte’s policy will look like, on both a domestic and international level. A lack of detail and scrutiny is a reason for worry and like Trump, there are lots of questions and contradictions, but that is as far as comparison should go. Duterte may represent a similar victory for a bigoted, loud-mouthed, populist politician, but his circumstances and his impact on the Philippines are particularly striking. Trump is the TV personality while Duterte has a rugged, less polished and more believable man-of-the people persona. So while they both swear a lot and have politically incorrect — sometimes downright misogynist — tendencies, the similarities only go so far.

The 71-year-old has been allowed to run as an anti-establishment figurehead due to a lack of media scrutiny. This is in spite of the fact that he has been mayor of Davao (the largest city in Mindanao) for 22 years and has served as a congressman. Trump is the political outsider and while Duterte cultivates a similar image it simply isn’t true. He is a trained lawyer and he and his family are developing into a powerful political clan.

Despite being the fourth fastest-growing economy in the world, second only to China in Asia, the Philippine economy — like its politics — is dominated by a few elite families. The striking inequality and widespread poverty are not new problems, but patience with what Duterte managed to paint as educated liberal American-sycophants in Manila, has run out. And Duterte has been allowed a platform — providing great copy for global syndication, but often distracting from the issue of how he will “eradicate crime and corruption in six months”.

Commentators, interviewers and news anchors in the country seemed reluctant to challenge him. Instead, they have focused on his claims that he “can love four women at the same time”. Protecting access to the foul-mouthed, self-confessed womanising “strongman” seems to have been their priority. Duterte will speak at length wherever a microphone is near; Trump, meanwhile, is now learning to be much more guarded, even around outlets from the political right, predominantly speaking at his own rallies.

The current President, Benigno Aquino, is leaving office after one frustrated term, as one of the few presidents to leave office still popular. It’s surprising then that the electorate has chosen such a drastically different figure. It would be easy to call this the end of democracy, though with voter turnout of more than 80 per cent, it is much more complicated. The concern domestically is that a Duterte presidency will carry over the same undertone of threat from the campaign. This was made explicit by a number of his supporters on social media who were quick to attack, especially when his most coveted attribute was ever questioned — his authenticity. The term “martial law” was trending across platforms.

The mayor who brought rough justice to a chaotic city (and has been accused of having used death squads ) made himself the obvious candidate for strong leadership. But memories of Ferdinand Marcos are still fresh; his corruption-riddled reign (1965-86) included a decade of martial law and many are obviously concerned that Duterte will wield a similarly arbitrary iron fist when it comes to the rule of law, breaking it when he chooses. Especially, if the former dictator’s son, Ferdinand Marcos, is elected as Duterte’s vice-president. Nobody really believes that Trump will be able to, or even seek to, implement martial law across America.

Many of these worries manifest at an international level, given Duterte’s comments on women and rape it is unlikely that Filipino women seeking compensation from Japan for crimes during the Second World War will find an ally in the new president. Similarly, following the sentencing of US Marine Scott Pemberton for the murder of Jennifer Laude, which raised the stakes of transgender rights and US-Filipino relations, Duterte has been openly dismissive on both topics.

There will be concern in Washington, most pressingly in the development of new and mothballed US military bases required as part of United States President Barack Obama’s pivot to Asia strategy that until now has relied on and received Filipino support — arguably at too great a cost. Duterte will be entitled to fight for a better deal for the country in relations with the US, but he has openly suggested that a deal with China over the disputed islands in the South China Sea could be more beneficial than being used as “Americas Pacific buffer”. While their politics may be different, this unpredictable new leader, and the timing of his rise, should worry the world much more than Trump ever could.

Comparing Duterte to Trump is tempting as a source of clickbait headlines, but it is inaccurate and risks becoming another act of cultural colonialism, especially given the history of the US in the Philippines. Cultural imperialism by the US in the Philippines has often meant local Filipino concerns have been viewed, acted on and disastrously managed through an American lens — as the new president well knows. Duterte may be dangerous enough without spurious comparisons to an American Republican presidential candidate.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Tom Smith is an academic specialising in political violence in South East Asia. He is currently the lecturer in International Relations for the University of Portsmouth at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell.