A few days ago, the columnist Michael Young asked in the Daily Star whether Lebanon would break apart if Syria succumbed to the proverbial political ax. Although he concluded that Beirut was likely to “weather the partition of Syria”, Young concluded that “society has to constantly reaffirm the principles of sectarian coexistence and avoid using the political system as a means of fulfilling partisan agendas” if it is to survive.

Lebanon was safe for now, Young predicted, even if he added that events in Damascus would batter Beirut for a while.

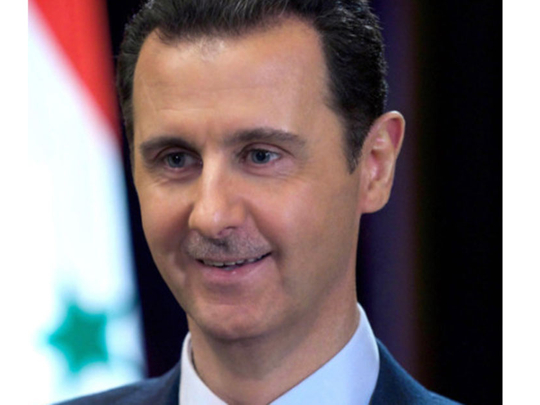

For his part, Michael E. O’Hanlon, the Co-Director of Centre for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at the Brookings Institution laid out a devastating proposal to deconstruct Syria into a confederal state, and while he concluded that the “ascendance of the [self-proclaimed] Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Daesh) as the major element of opposition to the Bashar Al Assad regime may not amount to an imminent threat to American security,” he stressed that “[Daesh’s] ... rise does place at much greater risk the security of Iraq, the future of Syria itself, and the stability of Lebanon and Jordan”.

A more realistic option, the well-connected O’Hanlon posited, was one that aimed to create safe zones, which will lead into a future confederal arrangement.

Are we on the brink of a full-scale deconstruction project that will alter Middle Eastern borders? Is the partition of several countries now inevitable?

Permanent fragmentations

Beyond the ongoing debate in the Obama administration to determine whether Iraq and Syria are indeed heading towards permanent fragmentations, several Arab commentators have joined the bandwagon that perceived the rise of independent “statelets”, especially as Iraq and Syria ran the risk of permanent implosions.

Fayez Sarah recently observed in the pan-Arab Asharq Al Awsat that “there is talk in political and media circles about the division of Syria as one of the ways to end the civil war”, an idea first developed by O’Hanlon and others in Washington, although Sarah did not rule out a putative role for the Al Assad regime to achieve it.

American versions of Arab deconstruction, at least as far as it is publicly known, do not foresee any future duties for Al Assad, the Baath Party, or various extremist groups. To be sure, Sarah relied on the post-First World War French mandate model that foresaw a united Syria but with autonomous areas, though what was under discussion in 2015 was something quite different.

Paris once contemplated a Alawite state (Dawlat Jabal Al Alawiyyin or, as it labelled it, État des Alaouites) alongside a Jabal Druze — thus creating two separate areas that enjoyed relative autonomy from 1920 to 1946 — that would not be in a loose association with Damascus.

In 2015, and unlike O’Hanlon who envisaged confederation, Sarah advanced the idea of full secession that, were it to materialise, would necessitate the formation of several statelets, including one ruled by the Free Syrian Army in the south, another controlled by the Al Assad regime either extending from Damascus to the Latakia coast or just focused on a coastal strip without the capital, a third that encompassed Idlib and Aleppo under Islamist forces, a fourth mini-state across the East around Raqqa and Hasakeh, while a fifth entity would be controlled by the Kurds along the Turkish border.

That was an ideal model for some even if Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan was adamant that Ankara would not allow the establishment of an independent Kurdish state in northern Syria for fear of rekindling secessionism at home. Still, the effective creation of a Kurdish Autonomous Region in Iraq set a precedent, which was likely to be duplicated elsewhere.

The answer to these dilemmas came from the erudite George Semaan of Al Hayat, who noted that recent losses in Daraa province highlighted why the Syria regime was in dire straits, which imposed inevitable political solutions on Damascus if the latter wished to save what was left of its authority. Notwithstanding the most recent Russian pledges made to Foreign Minister Walid Al Mua’llem, Moscow has toyed with the idea of abandoning Al Assad, which would be an unprecedented development in its own right. Be that as it may, the consequences of such events on several countries were all too real.

In his elaborate memoirs, Camille Chamoun, the former Lebanese president, stated that he did not fear for his country to fracture along sectarian lines, until after Iraq fell apart. Such a scenario, envisaged Chamoun, would doom Lebanese unity even if few contemplated the current Arab deconstruction that, for better or worse, weathered the winds of change in the post-Second World War era. For no matter how unpalatable the deeds of extremist groups might be, the breakdown of Iraq and Syria — and, perhaps, Lebanon and Jordan — were bound to be even more troubling. Those who are in the deconstruction business may please one or more local actors to foster sectarianism, though it is fair to ask whether blowback is on anyone’s mind.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Iffat Al Thunayan: An Arabian Queen, London: Sussex Academic Press, 2015.