In searching for a scenario that best encapsulates the current situation the people of Greece find themselves in, while also mirroring their character, I came across a tale online that puts into perspective both components of the prevailing scenario.

The anecdote, when observed in its simplicity, could well be the synopsis of Greece’s economic woes.

‘It is a slow day in a little Greek village. The rain is beating down and the streets are deserted. Times are tough, everybody is in debt and everybody lives on credit.

On this particular day, a rich German tourist driving through the village, stops at the local hotel and lays a €100 (Dh405.5) note on the desk, telling the hotel owner he wants to inspect the rooms upstairs in order to pick one to spend the night in. The owner gives him some keys and as soon as the visitor has walked upstairs, the hotelier grabs the €100 note and runs next door to pay his debt to the butcher.

‘The butcher takes the €100 note and runs down the street to repay his debt to the farmer. The farmer takes the €100 note and heads off to pay his bill at the supplier of feed and fuel.

The guy at the Farmers’ cooperative takes the €100 note and runs to pay his bill at the taverna. The proprietor slips the money to the local bar girl, who has also been facing hard times and has had to offer “services” on credit. The girl then rushes to the hotel and pays off her room bill to the hotel owner with the €100 note.

‘The hotel owner then places the €100 note back on the counter so the rich traveller will not suspect anything. At that moment, the traveller comes down the stairs, picks up the €100 note, states that the rooms are not satisfactory, pockets the money and leaves town.

No one has produced anything. No one has earned anything and yet, the whole village is now out of debt and looking to the future with optimism.’

That — if the Greeks had their way —is how they would like their bailout package to be custom-made.

The current scenario being played out in Europe is not so much a Greek tragedy as it is a drachma. Throughout the course of their history, Greeks have been unaccustomed to two very powerful words: Compromise and concession. They would favour compromise to sudden death, but only if the situation is cloaked in valour rather than realism and logic.

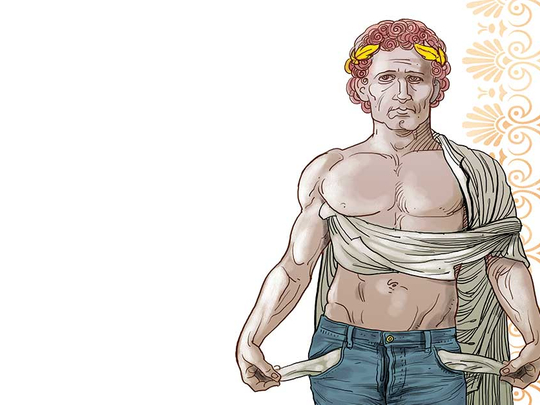

The bottom line is Greeks insist on looking good in life and death, success and failure. The script must always make allowance for a sense of romanticism. It is the cornerstone of the celebrated concept of a Greek tragedy where the protagonist, usually a man of importance and outstanding personal qualities, falls to disaster through a combination of personal failings and a failure to deal with circumstances that are out of his control

There is a certain irony in this, given that ancient Greece was the theatre of civilisation, philosophy and rationality — all of which were effectively applied to politics, society and economics. Times have changed. Sadly, the Greeks of today have not been able to emulate the examples set by their celebrated forefathers. Curiously, they conveniently take refuge in their glorious past during moments of stern self-examination.

Searching for a flawless hero

Right now, the Greeks are desperately searching for a flawless hero. He must be like Alexander The Great, or Leonidas, with the mental capacities of Homer, Aristotle, Socrates and, in order to get the sums right, the mathematical capabilities of Pythagoras and Archimedes.

It is a tragedy of Grecian proportions that they had to settle for the likes of Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, who ordered the recent referendum, in the hope that he would lose it. Tsipras had underestimated his popularity and was shocked when he won and lost the opportunity of resigning from office and handing over the country’s myriad economic woes to a successor! He now has to lead his people by fighting a continent and an adversary he should not have messed with: Angela Merkel.

The prime minister celebrated his pyrrhic victory by sacking his maverick finance minister Yanis Varoufakis who, after all his initial bluster against the Germans, parked his bike, swallowed his pride, and then some ale, after tendering his resignation, at the local pub.

In a sense, Varoufakis was a bit of a ‘hypocrites’ (Greek word for actor, but go figure). He had the ingredients (or so everyone thought) of a modern-day Leonidas, who stared down 250,000 Persians under the leadership of King Xerxes, with a rag-tag outfit of 300 Spartans and 700 Thespians (not to be confused with actors, unless you have watched Gerald Butler unleash his sword and scream ‘This is Spartaaaaaa’ in the film 300). The film captures a particular segment between Xerxes and Leonidas, which encapsulates the core of the sheer irresponsibility of the Greek spirit and Varoufakis’s philosophy.

Xerxes: “A thousand nations of the Persian Empire will descend upon you. Our arrows will blot out the sun.”

Leonidas: “Then we will fight in the shade.”

Varoufakis ran out of the fight and gave way to Euclid (meaning renowned and glorious) Tsakalotos. The latter scribbled the two words ‘No Triumphalism’ on a headed notepaper of the hotel he was staying in, before attending his first European Union meeting as Finance Minister of Greece.

Tsakolotos was soundly rebuked by those present, more notably by Wolfgang Schuble, his wheel-chair bound 72-year-old German counterpart, who had brought the curtains down on Varoufakis, ensconced from his perch, for not having done his homework and presenting a list of solid reforms to help his distressed country receive distress funds. It was a classic case of sinking to the debts of misery.

Tsakalotos’s historical namesake, the famous Euclid of Alexandria (323-283 BC) has often been referred to as the Father of Geometry. Our current day protagonist had run out of angles in the first instance. Perhaps Tsakalotos was over-reliant on the words of Socrates who had said that, “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing”.

This brings us to the Greeks themselves. They are being robbed of their dignity with every passing day. They have also become victims of their own referendum. Did they apply logic, or was it once again a case of Greek pride coming in the way of reality?

Perhaps, it was the latter emotion. Socrates believed that wisdom was parallel to one’s ignorance. One’s deeds were a result of this level of intelligence and ignorance.

But even Socrates was human. Eventually he was sentenced to death by poison. The narrative of his passing is found in Plato’s ‘Phaedo’. After drinking the poison Socrates was made to walk till his legs felt heavy. The man who gave him the dose pinched his foot but Socrates only felt a numbness. This sensation eventually travelled to his heart and he died. Before dying, Socrates spoke his last words to Crito saying, “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. Please, don’t forget to pay the debt.”

Who knew ...