The Myanmar government recently ended the ‘clearance operation’ mounted since October last year in the country’s troubled Rakhine State. The operation was launched after, in a first incidence of its kind, alleged Rohingya militants attacked Myanmar border posts close to the Bangladesh border, killing nine policemen.

Approximately 1.3 million-strong improvised Rohingya Muslims are confined in camps in Myanmar’s Rakhine state bordering Bangladesh. Both states consider them illegal migrants from the other, denying them civic rights. Another million live in Bangladesh, Southeast Asia, Saudi Arabia and India.

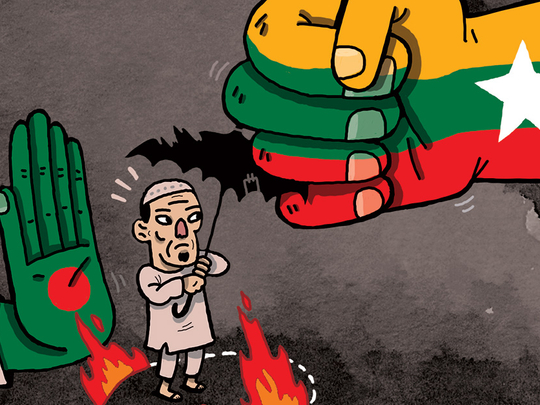

Following the border attacks, the Myanmar military-dominated government, in ruthless acts of retribution, killed more than a thousand innocent civilians. Analysis of satellite images by Human Rights Watch, a United States-based think tank confirm that the military set fire and destroyed 1,500 Rohingya homes. Survivors and escapees to Bangladesh confirm systematic rape of Rohingya women. The crackdown, aimed to fully disarm any semblance of militancy among the Rohingya, has sent at least 65,000 Rohingya across to Bangladesh and thousands internally displaced, says the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). According to the IOM, more than 120,000 Rohingya fled increasingly repressive conditions in Myanmar during 2012 to 2014.

The International Crises Group (ICG), a Brussels-based think tank in a report — ‘Myanmar: A new Muslim Insurgency in Rakhine State’, published on December 16, 2016, has warned that recent developments threaten prospects of stability and have serious implications for Myanmar and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) as a whole. The government, the ICG thinks, faces a huge challenge to ensure that the violence does not escalate and the inter-communal tensions are kept in check. Failure to address the long-standing Rohingya grievances risks generating a spiral of violence, says the report.

The beginnings of an armed resistance, Myanmar’s military crackdown and surge in international concern are some of the developments that are now reshaping conflict over the Rohingya. Its spillover into neighbouring Bangladesh and the Asean region will have far-reaching consequences.

In dealing with nearly half a million Rohingya refugees with no civic rights, Bangladesh is caught in a dilemma. For some, the Rohingya influx, reminiscent of times when millions of Bangladeshis took refuge in neighbouring India during the country’s liberation war in 1971 evokes sympathy. Others argue that it is unlikely that the Rohingya will ever be allowed to return home in Myanmar. Therefore, even a partial acceptance of Rohingya will vindicate their (Myanmar’s) stand that these people are Bangladeshis who have illegally entered and are claiming citizenship in Myanmar.

Bangladesh, facing growing extremism at home, is obviously concerned at the beginnings of an armed resistance next door. Meanwhile, Rohingya, shunned both by Myanmar and Bangladesh, may indeed find that resort to armed struggle may be the only redemption for them.

Asean, of which Myanmar is a member, faces a particular risk and bears a special responsibility to engage with Myanmar to prevent the situation to deteriorate further. There are pockets of restive Muslim population within certain Asean countries, but none faces the desperation of Rohingya.

Asean patiently nurtured Myanmar’s slow transition to democracy, which has led this reclusive state back into the mainstream. Until now, except for countries directly affected, Asean’s reaction to the brewing crises has remained lukewarm. Asean’s reticence to act effectively, when the crises erupted in 2015 over thousands stranded at sea, at the hands of human traffickers, drew widespread criticism.

Malaysia, the most affected and therefore vocal among the Asean, believes that a situation that has fuelled a large exodus of refugees, potentially destabilising the region, is no more an internal affair of Myanmar. Prime Minister Najeeb Razak has called the military campaign genocide and blamed the Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi for not doing enough to prevent action against the Rohingya.

Asean works on the basis of consensus and this is the reason of its paralysis in taking a more active role in the Rohingya crises, involving one of its own members. But now with growing Rohingya desperation, leading to beginning of violent reaction against state, Asean needs to demonstrate a collective resolve in nudging Myanmar towards accommodating the Rohingya aspirations.

Myanmar government, instead of using disproportionate force, must adopt policies to address the Rohingya sense of hopelessness and despair. Short of an accommodating policy approach by the government, offering hope to the community, the risk of spiralling violence and mass displacements are likely to continue. This could create conditions for further radicalising sections of Rohingya population that could be exploited by arms merchants and others to pursue their own agendas. After all, when people have nothing more to lose they resort to violence.

Sajjad Ashraf is an adjunct professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. He was a member of Pakistan’s Foreign Service from 1973-2008 and served as Pakistan’s consul general to Dubai and Northern Emirates during the mid 1990s.