Crisis simulations needed, not debates

Great US presidents make the right calls in moments of crisis. They reason through unexpected problems. They ask good questions and sift through new information quickly

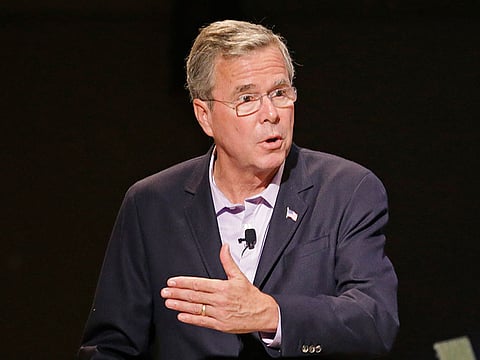

Every election year, US potential commanders in chief spend hours — days, really — preparing for the debates. They practice their comebacks and refine their zingers. Advisers quiz them on obscure foreign policy topics and inane pop-culture references. When they step onto the stage (as Republicans will do this week), the candidates strive to sound smart but not condescending, knowledgeable but folksy.

All of which will be very boring and will tell Americans very little about the kind of leaders these candidates would actually be.

Instead, let’s let those aspirants try out for president by putting them in charge of a simulated crisis. Imagine that a bus is blown up in downtown Chicago, killing 40 people, and Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) claims responsibility. Imagine that a cyberattack takes down the power grid in Atlanta in the middle of a summer heat wave. Imagine that a sudden financial market collapse leaves several mid-size commercial banks temporarily unable to fulfil depositor withdrawals and instead they must rely on FDIC insurance.

How would the candidates think through their options? How would they react? And wouldn’t we gain more insight by examining their responses, rather than by discussing why one hopeful sighed inappropriately or checked his watch? After all, Americans learned more about John McCain when he failed to negotiate a solution to the 2008 financial crisis after suspending his campaign than they did when he called US President Barack Obama “that one” in a debate two weeks later.

Great presidents make the right calls in moments of crisis. They reason through unexpected problems. They ask good questions and sift through new information quickly. They cut through ambiguity and thoughtfully weigh trade-offs. A crisis simulation would test these qualities in ways the debate format obviously does not. Americans want leaders who can resolve a Cuban missile crisis, not those who will stumble confusedly through a Hurricane Katrina disaster.

Such a simulation would have to be carefully planned, with former government officials or other expert actors playing key roles based on meticulously rehearsed stories. In the banking simulation, performers would portray the heads of regulatory agencies and large financial institutions. One could be instructed to offer bad advice — would any of the candidates fall for it? Candidates could also bring in their own advisers and would be free to call anybody they wanted during the simulation (just like the Who Wants to Be a Millionaire lifeline).

Presidential hopefuls could be fed the details of the crisis over a couple of hours, from “advisers” and faux live news coverage. Markets could “respond” in real time, with financial pundits offering different advice: The government should immediately buy up the failing banks! Don’t intervene, it will only spur more panic! It’s easy for candidates to criticise bailouts or government intervention in the abstract. But what would they do while staring into the abyss of a collapse, faced with only bad and worse options?

At the end of the simulation, each candidate would give a short speech, summarising his or her response so far and outlining plans to confront the crisis ahead.

Film crews could record the entire simulation, then television producers could turn it into a reality-TV special. Make all the footage public, and journalists could comb through it and analyse who handled the situation best and why. Candidates could critique each other’s responses. Americans would also learn about the quality of advice the candidates get (crucial, since all presidents rely on advisers, contrary to their pretensions to omniscience).

Instead of spending the week after a debate arguing over who had the best comeback or the worst gaffe, maybe Americans would get the kind of Monday-morning quarterbacking that touches on some of the challenges of actually being president. Maybe voters would learn a few things about the mechanics of the executive office. They would also get a real test of how well their candidates understand the responsibilities of different federal and state agencies. In the Atlanta power grid attack scenario, would a potential president know who had authority over what, and how to lead and coordinate a response with many overlapping jurisdictions? How well could the candidate calm the nation in a volatile moment of fear?

Certainly, some scenarios might favour candidates with more federal government experience. But while being an “outsider” is appealing to regular folks, a keen understanding of the Washington bureaucracy is important to the job of governing. And candidates who lack D.C. experience can benefit by demonstrating that they’re fast learners, capable of asking good questions.

Presidential hopefuls should embrace the opportunity to be tested like this. After all, the simulations would offer a chance to (at least in theory) “look presidential.” It’s hard for candidates to convey how they would handle the demands of the office by making general promises. Here’s a way for them to show, rather than tell. And there’s another benefit, too — this exercise might help prepare someone to be president, training that only incumbency offers now.

The election season is long enough to feature several of these simulations, covering a range of domestic and foreign challenges. Why not try this out before primary voting starts? Now that Americans are pretty much through with the official candidacy announcements, they’re about to enter months of dull campaigning, with hordes of political reporters desperately trying to find something interesting to write about. This would spice things up.

Some argue that debates are worthwhile because they provide unscripted moments that help reveal a candidate’s personality. But really, beyond the occasional flub, they don’t. And Americans already get a good sense of which candidates can speak well and lay out a clear vision through the hundreds of speeches and interviews they give. The debates don’t add to this knowledge. Candidates may have plans for what they’d like to accomplish in office, but in the colourful words of Mike Tyson, “Everybody’s got a plan until they get hit in the mouth.” Americans want to know what happens when a candidate gets hit in the mouth.

Debates reward candidates for one-line zingers and condition voters to expect slogans as solutions. Crisis simulations would reward thoughtful responses and could be designed to address complex questions, forcing real trade-offs. Maybe they could even change the conversation about what we want in a president. At the very least, they’d be a whole lot more entertaining than the boring talk-fests Americans have now.

—Washington Post

Drutman, a senior fellow in the political reform program at New America, is the author of The Business of America Is Lobbying: How Corporations Became Politicized and Politics Became More Corporate.